This article analyses Henri Verbrugghen’s role as conductor and organiser... South Wales State Orchestra, which was the first permanent professional... Music, Finance, and Politics: Henri Verbrugghen and the New South...

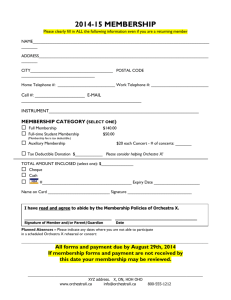

advertisement