Trail of Tears

advertisement

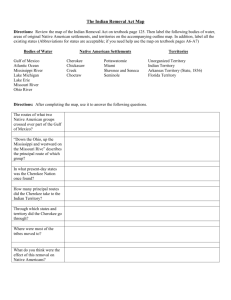

Trail of Tears In 1829, President Andrew Jackson urged Congress to set aside a large area west of the Mississippi as a new home for the southeastern tribes. Unless the Indians were removed from the East, he warned, their way of life would “disappear and be forgotten.” This proposal triggered a storm of protest. Most Americans believed the plains west of the Mississippi to be the “Great American Desert.” Sending Indians into this wasteland, some argued, was to sentence them to certain death. Ignoring such arguments, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830. The act created a new Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma and allocated funds to assist with the removal of Indians to that area. The Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek gave up their eastern lands more or less voluntarily. Those who refused to move willingly were rounded up by troops and marched westward in handcuffs. Most of the Cherokee and Seminole, however, refused to leave their homelands. Led by a young chief named Osceola, the Seminole defied removal orders and fled into the Florida swamps. For years, the army struggled to drag the Indians out of their hiding places and ship them west. In the end, only part of the Seminole were sent to Indian Territory. Meanwhile, the Seminole War cost the United States more in both lives and money that any other Indian conflict before or after. In 1838, after eight years of resistance, troops descended on Georgia to forcibly remove the Cherokee. The soldiers fanned across Cherokee lands, seizing men from the fields, dragging women from their kitchens, and snatching children from their play. William Coodey, the Cherokee chief, wrote that “multitudes were allowed no time to take anything with them, except the clothes they had on…Many Cherokees, who, a few days ago, were in comfortable circumstances, are now victims of abject poverty.” A Georgia soldier who later served in the Confederate army wrote, “I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever saw.” The army kept the Cherokee penned up in camps throughout the stifling summer. When they finally began their westward journey in the fall, icy winds and rain made travel a misery. Four thousand Cherokee, or about one in four, died on the forced march to Indian Territory. Their shallow graves were the only markers left by the Cherokee on the route they would forever remember as the “Trail of Tears.”