American Revolution

advertisement

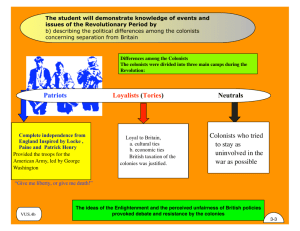

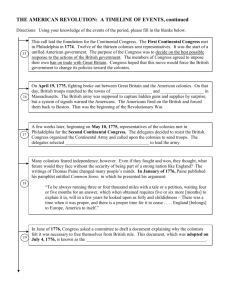

American Revolution When the Second Continental Congress met in May of 1775, its goal was to pressure Parliament into halting its taxation and other violations of the colonists' rights as Englishmen. Until that change occurred, Congress vowed to lead the colonists in their effort to stop further abuse of their rights. Toward that end, Congress created the Continental Army and placed George Washington in command. Despite bloody battles between the Americans and British during the closing months of 1775, Congress had no intention of declaring independence from Britain. It was merely fighting to force a change in Parliament's colonial policy. But as the fighting continued into 1776, it seemed clear that Parliament would not change its ways. Colonists increasingly became convinced that America had to separate itself from British rule. Spurred on by pro-independence arguments, such as that in Thomas Paine's "Common Sense," the Second Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. In the opinion of the Congress, the colonies were now independent states. In the opinion of Britain, however, the colonies were still colonies which had to be forced into submission. After July 4, 1776, the Continental Army was no longer fighting for colonists' rights -it was fighting for American nationhood. But the war for independence at first went poorly for the American forces. The Patriots could not hold major cities such as New York and Philadelphia. Washington's army barely survived these early defeats and the cold winter months at places like Valley Forge. To make matters worse, Loyalists (colonists who supported Britain) and Iroquois Indians joined the British forces. But a change in fortune came in 1778 when a British force was defeated at Saratoga by General Gates and his army of Patriots. News of this victory helped persuade France to become America's ally. Finally in 1781, with French help, General Washington forced the surrender of a large British army at Yorktown. Britain's defeat at Yorktown, as well as pressing military problems in Europe, made Britain eager to end the war. In the Treaty of Paris (1783), Great Britain finally recognized the independence of the United States. In the treaty, Britain also ceded to the U.S. territory westward to the Mississippi River.