1 LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY

advertisement

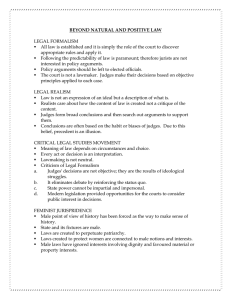

1 LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2004 JURISPRUDENCE OUTLINE ALL STUDENTS PLEASE NOTE: The outline below is intended to assist students in following the lectures in the course and in understanding the recommended reading. The outline is not a substitute for the lectures and reading. The outline is not intended to be comprehensive. Students who have merely familiarised themselves with the outline but not attended the lectures and read the prescribed text and readings will be inadequately prepared for the exam and at substantial risk of failure. Commencing with the November 2001 semester, examination questions will increasingly ask students to apply the concepts and arguments taught in the course to an issue or problem. Students will be best prepared to deal with the paper who have attended the lectures or weekend schools and read widely. LECTURE 1 THE DOCTRINE OF PRECEDENT AND THE AMERICAN REALISTS INTRODUCTION TO THE COURSE Reasons for studying legal philosophy The relationship between law and philosophy The course will concentrate on three principal themes, namely: 1. What is the nature of law and what does it mean to say a law exists? 2. How do lawyers reason, is there a special type of legal reasoning? 3. What is the relationship between law and morality? Christopher Birch April 2004 2 THE DOCTRINE OF PRECEDENT The doctrine of precedent depends upon the principle of stare decisis, the principle that courts in a hierarchy are bound by the decisions of those above them in the hierarchy. That part of a decision that binds a judge is the ratio decidendi. A key problem for the doctrine of precedent is determining the ratio of cases. Why Ought We to Follow Past Decisions? Ought we to decide case B in a particular fashion merely because case A was decided in that fashion in the past? Chaim Perelman argued that the doctrine of precedent reflects the principle of formal justice. The idea that like cases should be decided alike. There are pragmatic arguments for following precedents. The need for citizens and lawyers to have guidance on how courts will behave in the future. If judges did not follow the law it could be argued that they are making the law. Judicial law making would conflict with the principle that the exercise of law-making power should have a democratic mandate. It would violate the separation of powers doctrine. What is the Ratio? Cross in ‘Precedent in English Law’ says: “The rule of law expressly or impliedly treated by the judge as a necessary step in reaching his/her conclusion, having regard to the line of reasoning adopted by him/her.” Attempts to provide a formal or logical scheme for extracting the ratio from past cases have been largely unsuccessful. See Wambaugh’s test. See Goodhart’s Theory. It appears to follow that the ratio of a case is what later judges decide the ratio to be. Would there be a difficulty, if any, if judges declared when they handed down decisions what the ratio of the decision was? Christopher Birch April 2004 3 THE AMERICAN REALISTS The American realists were a group of jurists writing at the end of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries principally in the United States. Some were judges and others were legal academics. Amongst the more prominent of the American realists were: Oliver Wendell Holmes (judge of the US Supreme Court) Karl Llewylnn (academic) John Chipman Gray (academic 1835-1950). Jerome Frank (academic, government lawyer and later US Federal judge). The American realists criticised what they called formalism or mechanical jurisprudence. The notion that cases represented rules and that these rules could be applied to the facts as found so that the verdict could be arrived at deductively. Legal reasons might still be a constraint on the type of verdicts that could be reached. (See Joseph Hutcheson, Martin Golding and Richard Wasserstrom). In 1930 Jerome Frank published Law and the Modern Mind. This advocated a much more radical version of American realism. Frank argued that, amongst other things: Legal reasoning could never be fully deductive In ascertaining the content of legal rules judges were only bound by whatever they considered the rule to be. They determined to what extent they were bound. The law is a rich set of rules with many ways of arguing to any particular result. The law contained such intrinsic complexity and uncertainty that judges could always formulate a respectable legal argument to justify any particular outcome of a case. In addition to the scope for judges to redefine the law, the outcome of the case was also determined by the factual findings and here judges again had a broad discretion as to what findings to make. In consequence of the above matters Frank argued that judges are in no logical sense ever constrained by previous decisions or by any abstract set of legal concepts. Judges are always free to justify any result they wish. Christopher Birch April 2004 4 A case study will be undertaken of the development of a line of precedent using the following decisions: Permanent Trustee Co v Freedom From Hunger (1991) 25 NSWLR 140 Troja v Troja (1994) 33 NSWLR 269 Public Trustee v Hyles (1993) 33 NSWLR 154 The historical context and implications of American realism A number of the American realists were social reformers who were concerned to show that the law was not a fixed body of rules but capable of adaptation. American realists argued that there could never be logically determinate answers and courts should be open about the fact that judges invent the law as they apply it. American realists argued that theories of legal reasoning should be able to provide reliable means of predicting what judges will do in the future. They criticised formalism as an inadequate predictive device. American realism led to studies of judicial psychology and judicial behaviouralism and the development of so-called jurimetrics. Point of view and legal theory The American realists looked at the legal system from the point of view of a lawyer or client wanting to know what the likely outcome of a case will be. Criticism of American realism One primary criticism is that it fails as a theory of justification. Telling judges that they invent the law as they apply it does not provide guidance as to how they should invent the law. Many lawyers still have a strong sense that there is a constraint on the outcome resulting from legal concepts. American realism does not explain this constraint. American realism appears to undermine the doctrine of the separation of powers. Christopher Birch April 2004