Increased Partnerships Through Service-Learning: Working With The Demands Of Accountability

advertisement

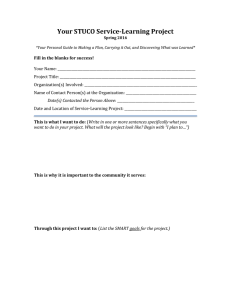

Increased Partnerships Through Service-Learning: Working With The Demands Of Accountability 1 Lynne A. Bercaw Teresa Davis California State University, Chico The increased pressure of accountability for both K-12 schools and teacher education programs can cause each level to draw more into themselves to focus on their respective demands. It is the increased demand of accountability, however, that begs us to strengthen our partnerships to draw on our respective expertise and resources as a means to increase student and teacher candidate achievement. This inquiry focuses on a K-12/teacher education partnership to increase civic engagement and civic responsibility for students and teacher candidates through service-learning. Findings from a pilot project of service-learning in a teacher education program revealed that resistance from teacher candidates and cooperating teachers were almost entirely based on accountability demands (K-12 standardized tests and the teacher performance assessment for teacher candidates). This study focuses on the second year of implementation of service-learning in a teacher education program and is guided by two research questions: (1) Does the involvement in service-learning influence candidates’ self-efficacy toward civic engagement? and (2) Is there a difference between the PACT scores of candidates who participate in servicelearning compared to those who do not? The inception of the second question is rooted in findings from the pilot year of implementation, which was voluntary for teacher candidates—most candidates who chose to not participate were reluctant to implement service-learning for fear it would negatively affect their achievement on the high-stakes Performance Assessment for California Teachers (PACT). This study is comprised of two groups—those who participate in service-service learning and a control group who does not participate. Data will include surveys for candidates and cooperating teachers, semi-structure interviews, and focus group interviews, as well as data the program already collects (PACT scores). Over the past few decades, there have been compelling theoretical and empirical studies that provide evidence for the benefits of implementing service-learning in teacher education and the K-12 classroom (see Erickson & Johnson, Eds., 1997 & Ladson-Billings, 2001). Specifically, several studies attest to the effectiveness of implementing service-learning in preparing teachers toward increasing student achievement and civic efficacy (Bell, Horn, & Roxas, 2007; Brown, 2005; Karayan & Gathercoal, 2005). However as the testing and assessment measures for both teacher candidates and K-12 students intensify, the rationale for creating the programmatic space for service-learning is overshadowed by the requirements mandated by state and national standards. As teachers’ primary role is to prepare students to be thoughtful, active citizens, the mission statement of the School of Education program on which this paper is based is “…to develop effective, reflective and engaged educators [and] to create a diverse, democratic, socially responsible society in which every student is valued (School of Education website, n.d.). Drawing primarily on a critical pedagogy in teacher education, service-learning calls for active engagement in one’s community (Dodd & Lilly, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 2001; Root, 1997) and for teachers to be “change agents” through service (Ladson-Billings, 2001). Service-learning “socializes teachers in the essential moral and civic obligations of teaching…fostering lifelong civic engagement, being able to adapt to the needs of learners with diverse and special needs, and being committed to advocacy for social justice” (Root, 1997, p. 43). Further, servicelearning provides teacher candidates with authentic opportunities to participate in the communities in which they live and teach (Dodd & Lilly, 2000). Context of the Study. The School of Education in which this study was conducted, is located in a state that requires a post-baccalaureate year or “fifth year” where candidates must complete a bachelors’ degree prior to earning their credential. Therefore, the challenge becomes how to scaffold the service-learning experience in a very short time. In contrast, programs that have an undergraduate degree and licensing program have a bit more time to build a progression of experiences (see Colby, Bercaw, Clark, & Galiardi 2009). The challenge for 1-year programs becomes how to provide experiences in service-learning where candidates have the greatest success and confidence for them to carry into their classrooms once employed. The School of Education at this state university is participating in a funded national partnership, “Preparing Tomorrow’s Teachers with Transformative Practice: Engaging All Learners in Service-Learning” (EASL), for two years. The goal of the project is to build a systematic implementation within each program of the School of Education (elementary, secondary and special education). Through the current participation in Project EASL as a sub-grantee of Duke University funded through the Corporation for National and Community Service, the School of 1 This study is funded by The Corporation for National and Community Service to The International Center for SL in Teacher Education at Duke University and NCATE Education’s focus has centered on articulating service-learning pedagogy throughout several programs (elementary and special education programs) in a more systematic, effective manner as well as developing stronger partnerships with public schools. One of the greatest challenges from the first semester, as shared by the teacher candidates, was the support of cooperating teachers. Therefore, the following semester we enlisted a cooperating teacher to be the liaison between the university and public school partners. Her responsibility was to communicate with cooperating teachers about service-learning and the opportunities for their teacher candidates and their elementary students. Despite this addition, the participation in the fall 2011 semester was less than that in the spring. The major reason reported both by teacher candidates and cooperating teachers was the demand of testing, which occurs near the end of the school year, usually in April. As the implementation of service-learning developed in the second year (2011-2012), the challenges for these three major participants (teacher candidate, cooperating teacher, and teacher educator) become evident, each with its own set of obstacles. For the teacher candidates it was both their high stakes “teacher performance assessment” and demands of coursework and student teaching. For cooperating teachers, it was the standardized testing of their students. For teacher educators, it was the challenge of designing a systematic implementation of service-learning where the pedagogy can actually be part of candidates’ assessment and to communicate to public school partners the research showing how this pedagogy increases student achievement. This study specifically addresses the following two questions: What strategies and practices have proven to be most successful in carrying out partnerships between schools of education and others in the community? How can schools of education improve partnerships with K‐12 schools? The study examines the efforts of a teacher education program and its K-12 partners to increase civic responsibility and engagement through service-learning. The conditions that support and hinder this collaborative effort are explored through survey data, teacher performance data and focus group interviews. Findings inform teacher educators of how best to support and strengthen partnerships between K-12 schools, teacher education programs toward civic engagement. References Bell, C. A., Horn, B. R., & Roxas, K. C. (2007). We know it’s service, but what are they learning? Prospective teachers’ understandings of diversity. Equity and Excellence in Education, 40(2), 123-133. Brown, E. L. (2005). Service-learning in a one-year alternative route to teacher certification: A powerful multicultural teaching tool. Equity and Excellence in Education, 38(1), 61-74. Colby, S. A., Bercaw, L., Clark, A. M., & Galiardi, S. (2009). From community service to service-learning leadership: A program perspective. New Horizons in Education, 57(3), 20-31. Dodd, E. L., & Lilly, D. H. (2000, Fall). Learning with communities: An investigation of community service- learning in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 22(3), 77–85. Erickson, J. A. & Johnson, J. B. (Eds.) 1997. Learning with the community: Concepts and models for service-learning in teacher education. Sterling, VA: Sylus. Karayan, S., & Gathercoal, P. (2005). Assessing service-learning in teacher education. Teacher Education Quarterly, 32(3), 79-92. Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan: The journey of new teachers in diverse classrooms. New York: Jossey-Bass. Root, S. C. (1997). School-based service: A review of research for teacher education. In J. A. Erickson & J. B. Anderson (Eds.), Learning with the community: Concepts and models for service-learning in teacher education (pp. 42-72). Washington, D.C.: American Association for Higher Education.