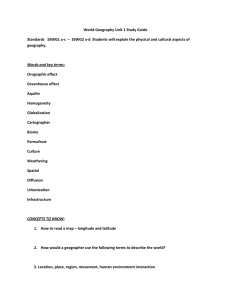

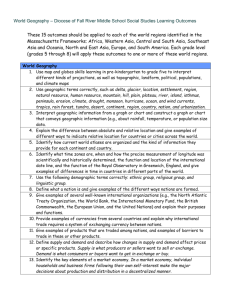

GEOG 390— Course Handbook Foundations in

advertisement