A speech is nothing more than an explanation of a... Most speeches are delivered to organized groups—business associations, civic groups,

advertisement

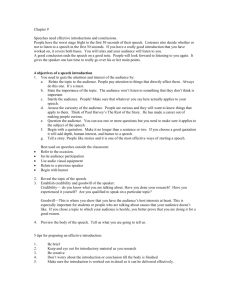

How to Cover Speeches A speech is nothing more than an explanation of a person’s thoughts. Most speeches are delivered to organized groups—business associations, civic groups, church groups, unions, guilds, etc.—and are on topics of specific or general interest to the audience. Speeches by candidates for public office are delivered to organized groups and, from the stump, to whoever gathers at the site. In any event, speeches are advertised well in advance of delivery to help ensure attendance. Covering a speech is the easiest assignment of all, particularly because: Reporters usually know all of the details well in advance: the name and background of the speaker, details about the audience and the place of the speech, and the reason for the speech. Copies of the speech are delivered to reporters either in advance of or during the speaking event, enabling reporters to follow the speaker’s delivery. The speech usually is about one or two topics and no more than 20–30 minutes long; and The speaking situation is in one place. Most speeches follow this three-part format: beginning, middle, end. The beginning of the speech sets the stage for the speech, tells its purpose; the middle details explanations and support for the speaker’s ideas; and the end presents the conclusion, the position of the speaker on the topic. The key to writing stories about speeches is to summarize the speech or to present one or two key points in the lead sentence. The following matrix will help you determine your lead for a speech story. Answers to the all-capital questions—WHO, SAID WHAT—must be in the lead of every speech story. Answers to the caps-and-lowercased questions—To Whom, Where, When, How, Why—may be placed in the first paragraph but not later than the second paragraph. WHO The WHO of the story is essential in stories about speeches. This is the person delivering the speech. If the person is widely known (someone in the news regularly), begin with the name and title (Mayor Jonathan Price). If the person is not widely known, begin with a description of the speaker (an assistant professor of biology) and place the speaker’s name in the second paragraph. SAID WHAT The SAID WHAT of the story is essential in stories about speeches. The SAID WHAT is either a summary of the speech or a description of one or two key points of the speech. The summary usually is at the end of the speech, in the conclusion section and is usually preceded by "in conclusion" or "finally" or "therefore" or “to sum up” or the like. It is the time in the speech when the speaker tells the audience briefly the reason for the speech and what the audience should know or should consider doing. To Whom The To Whom of the story is the speaking event—the audience and the reason for the speech—and usually is placed in the second paragraph. Include the name of the group, the reason for the speaking event (annual banquet, political campaign, civic club luncheon, etc.), and the number of people present. Be sure to mention anyone of importance, such as elected officials, and whether and how frequently the speaker was interrupted by applause. The size of the audience is available through several means. In an outdoor event, the most reliable source is a police official, because the police are used to handling crowds and can estimate size fairly accurately. In a paid-for event—an auditorium, a hotel dining room—ask the proprietor or manager for the “gate,” the number of paid admissions or meals served. In a small event, count the number of attendees yourself. If a gate is unavailable and you know the number of seats in an auditorium, estimate the number of attendees by sight. Where The Where of the story is the place of the speech: city, building, room number, etc. Sometimes, it is built in: New Orleans Rotary Club. When The When of the story is the day or date, and sometimes the hour, of the speaking event. It is never recently, which is vague and meaningless. How The How of the story is not always present in stories about speeches. When it is present, however, it must be included. Why The Why of the story is the reason for the speech and the speaking event. Usually, this is built into the description of the To Whom. So What After you have written your lead, read it aloud and listen to the flow of language. Ask yourself if what you have written tells the whole story of the speech, if what you have written summarizes the speech or presents one or two key points. If not, rewrite the lead. If your verb is “spoke about,” rewrite the lead because “spoke about” tells readers nothing more than the topic of the speech. Those are called “speaker-spoke” leads because they tell readers only that someone spoke. Tell readers what the speaker said, not that the speaker said something or what the speaker spoke about. The Story The key points in a speech story are the speaker and what the speaker said, a summary of the speech. The lead should follow this format, if the speaker is in the public domain: Dallas Mayor Jonathan Price [WHO and built-in Where] urged members of the Chamber of Commerce [To Whom] to support the city’s plan to increase property taxes [SAID WHAT] to provide more recreational parks [Why]. The mayor was the keynote speaker at the annual CofC awards banquet that attracted 125 members and their spouses and guests. Or your lead should follow this format, if the speaker is not in the public domain: The president of the DPS Co. [WHO] urged members of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce [To Whom and built-in Where] to support the city’s plan to increase property taxes [SAID WHAT] to provide more recreational parks [Why]. President Andrew Hampden was the keynote speaker the annual CofC awards banquet that attracted 125 members and their spouses and guests. Thereafter, alternate paragraphs of information with paraphrased statements and quotations. Select only quotable, meaningful, quotations. If you can paraphrase a quotation better, the quotation is not quotable. Notes If a question-and-answer session follows the speech, use the information, but identify that information as being from the question-and-answer session and not as being part of the speech itself. In writing about a political campaign speech, include the name, title, and affiliation of the person introducing the speaker because it indicates the political strength of the speaker in that community. In other speeches, identifying the introducer is your decision. It is proper to use partial quotations in the lead. But do not begin a speech story with a full quotation. Quotations lifted from a speech do not lend themselves to lead material because they do not summarize the speech. In addition, using a full quotation as the lead requires a second sentence that usually begins, "That is the position of the president of the DPS Co. who spoke to. …" Such an approach is poor writing and should be avoided. Do not end a speech story with "in conclusion" or "finally" or "concluded" or "in closing," etc. Information in the conclusion of a speech usually belongs in the lead and should not be repeated at the end of the story. Titles of speeches and themes of conventions and speeches are meaningless to readers and a waste of words. Omit them from the story. Some speeches are titled “As I See It” and “The View from the Capitol,” both of which tell readers nothing. Convention themes frequently are titled “Frontierland” and “New Beginnings,” equally meaningless. "Said" is the most applicable and appropriate verb of attribution; use it frequently. It has no hidden meanings, and it hides in the story. Otherwise, the verb of attribution must reflect the speaker’s meaning: "warned," "urged," "cautioned," "called for," "suggested," etc. "Stated" and "added" generally have no place in a speech story. Before using any verb of attribution other than "said," check the dictionary definition for meanings and usage. Do not trust your memory or your normal use of the verb. For example: "refute" requires solid evidence; people may "deny" anything, even the truth; only officials really “state” anything, and only occasionally; and, because most speeches are prepared well in advance, seldom is anything ever “added” to a speech. Avoid such verbs of attribution as "discussed," "explained," "addressed," and "spoke" because they tell readers nothing. At the close of any speech, you may approach the speaker for additional information. If you use the additional information in your story, be sure to explain that it was not part of the speech.