TITLE PAGE Title Running Title Key words

advertisement

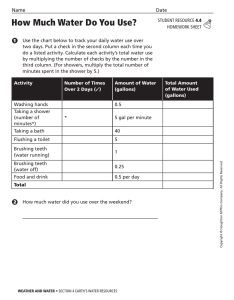

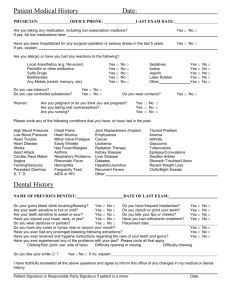

1 TITLE PAGE Title National levels of reported difficulty in tooth and denture cleaning among an ageing population with intellectual disabilities in Ireland Running Title Difficulty tooth brushing Key words Ageism, Intellectual Disability, Tooth Brushing Authors Mac Giolla Phadraig C 1,2, el-Helaali R 1, Burke E 3, McCallion P 3,4, McGlinchey E, McCarron M 3, Nunn JH 1,2 Corresponding Author: Caoimhin Mac Giolla Phadraig, Lecturer in Public Dental Health (Disability Studies), Department of Child and Public Dental Health, Dublin Dental University Hospital, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland, Ph +35316127337 Fax +35316127298 macgiolla@dental.tcd.ie 1 Dublin Dental University Hospital, Department of Child and Public Dental Health, Dublin, Ireland 2 School of Dental Science, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland 4 School of Social Welfare, University at Albany, Albany, Canada 2 ABSTRACT Aims and objectives: This paper aims to describe reported difficulty and frequency in carrying out oral hygiene practices among an ageing population with intellectual disabilities in Ireland; Methods: This cross-sectional survey was based on a Nationally representative sample of people with intellectual disability over 40 years of age, randomly selected from a National Intellectual Disability Database as part of the first wave of the Intellectual Disability Supplement to The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (IDS-TILDA). Level of reported difficulty was used to categorise the sample into three groups: those reporting no difficulty, those reporting some difficulty and those who cannot care for their teeth / dentures at all. Summary statistics and bivariate correlations are reported based on this categorization. The sample was further categorized into those with and without reported difficulty cleaning their teeth / caring for their dentures, for purposes of logistic regression. Independent variables correlating (p < 0.05) with level of reported difficulty brushing / cleaning dentures were included in this regression model to identify factors predictive of difficulty caring for teeth/ dentures; Results: The mean age of participants was 54.1 years (SD 8.8). Out of 753 participants, 412 (55.5%) reported no difficulty cleaning their teeth / dentures, 159 (21.3%) had some or a lot of difficulty and 172 (23.2%) reported that they could not clean their own teeth / dentures at all. The regression model showed that type of residence, increasing level of ID and the presence of reported oral problems were predictive of reported difficulty cleaning teeth/taking care of dentures. Conclusions: This study showed that most people with ID in Ireland report no difficulties cleaning their teeth or taking care of their 3 dentures. Even among those with some difficulty, the exact level of difficulty varied from little difficulty to complete inability. INTRODUCTION Plaque is a key aetiological factor in oral disease, particularly dental decay and periodontal disease. Effective tooth brushing is a fundamental cornerstone of controlling plaque, provided the cleaning is sufficiently thorough, and performed daily, along with interdental cleaning (Loe, 2000). Nevertheless, people are often ineffective at adequate plaque control (van der Weijden and Hioe, 2005). This difficulty is amplified among people with intellectual disability (ID), where poor oral hygiene is a frequent finding (Anders and Davis, 2010, Davies and Whittle, 1990, Shaw et al., 1990) and may go some way in explaining why adults with ID have poorer oral health outcomes than other populations (Glassman and Miller, 2003, Elliot et al., 2005, Anders and Davis, 2010). Impaired physical coordination and cognitive ability are just two reported barriers reported to limit some people who have an intellectual disability in daily tooth brushing (Owens et al., 2006, Nunn, 1987). Tooth cleaning is therefore difficult for many people with intellectual disability, meaning they may rely on others to have their teeth cleaned (Faulks and Hennequin, 2000, Pradhan et al., 2009b, Stanfield et al., 2003). While recent guidelines (British Society for Disability and Oral Health/Faculty of Dental Surgery of Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2012) provide guidance in techniques for making tooth-brushing 4 easier for people with intellectual disabilities, staff who care for them are infrequently trained (Crowley et al., 2005, Stanfield et al., 2003) and oral healthcare sometimes may not be a priority (Rawlinson, 2001). Tooth cleaning and denture care may also be difficult. One researcher noted that 68% of residents in one institution required some form of physical intervention to perform routine oral care (Connick et al., 2000). People with ID are increasingly ageing (Bittles et al., 2002) and with advancing age come changes to health status and health needs for people with ID (Evenhuis et al., 2012) as well as changes in social circumstances, such as residential setting (Kelly and Kelly, 2011), which has previously been shown to predict difficulty brushing (Pradhan et al., 2009a). It is unclear how the ageing process will affect their ability to care for their teeth and dentures. What implications this may have for those who help them maintain their oral health, as well as those who plan and deliver dental services for them. Aim: This paper aims to describe reported difficulty in carrying out oral hygiene practices among an ageing population with intellectual disabilities in Ireland. METHODS Design This is a cross-sectional survey based on data collected via the first wave of the Intellectual Disability Supplement to The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (IDS-TILDA), which is a multi-wave longitudinal study of older adults with intellectual disabilities. Survey instruments and methods were tested in an extensive pilot study (McCarron et al., 2009) The Faculty of Health Sciences 5 research ethics committee in Trinity College Dublin and all participating services granted ethical approval. Sample A Nationally representative sample of 753 people with intellectual disability over 40 years of age, were randomly selected from a National Intellectual Disability Database in Ireland (Kelly et al., 2008). Data collection All participants were sent invitation packs, through gatekeepers, designated individuals working in a range of disability services who, as per requirements for ethical approval of this research programme, verified participants’ willingness to participate prior to facilitating contact with research team. These packs included accessible formats of all documentation for invitees and their families and supporting staff. Concurrently, the research team provided information seminars. Eleven researchers, who underwent rigorous training and had extensive experience with people with ID, collected data using a two-stage data collection technique including a postal pre-interview questionnaire, followed up with faceto-face interviews. Respondents received support in answering questions where needed, by using others involved in their care (proxies). In addition to demographic data, items in the oral hygiene section consisted of six closed questions. Table 1 lists the items included in this report. Table 1 about here Analysis Data analysis was carried out using SPSS v.19 ®. Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic data and oral hygiene practices. This summarized the demographic and oral health related variables for the group as a whole. The 6 group was also categorized by level of reported difficulty carrying out oral hygiene practices allowing further bivariate analyses of the relationship between the dependent variable – reported levels of difficulty cleaning teeth / taking care of dentures and other variables. To this end, the sample was divided into three groups based on reported level of difficulty cleaning teeth / dentures (Table 1, Question 5). Participants reporting Some difficulty or A lot of difficulty were grouped together under the heading Some Difficulty for purposes of analysis. Correlations between the dependent variable: Reported level of difficulty and independent variables were tested using Pearson’s Chi Square. Independent variables found to correlate with reported level of difficulty in bivariate analyses (p < 0.05) were then included in a binary logistic regression model to identify factors predictive of reported difficulty brushing / cleaning dentures. To facilitate modeling, the outcome variable was re-categorised into a binary variable: those with difficulty and those without difficulty cleaning teeth / taking care of dentures. RESULTS Demographics There were more females than males in this study. The mean age of participants was 54.1 years (SD 8.8, range 41 -90 years), with almost half of participants between 50 – 64 years. Table 2 summarises demographic data for the total sample (n = 753). Table 2 about here Reported difficulty cleaning teeth / taking care of dentures The majority of participants reported no difficulty cleaning their teeth / dentures 7 (n=412, 55.5%). A total of 331 (44.5%) participants reported difficulty: 105 (14.1%) had “some difficulty” and 54 (7.3%) “a lot of difficulty” (this meant that 159 (21.3% of the total sample) were categorized for further analysis as having Some difficulty) and 172 (23.2%) could not care for their teeth or dentures at all. Those reporting difficulty (n=331) were asked if they received support from others in cleaning teeth / dentures and 140 (42.3%) said yes, they did so with support, while 172 (52.0%) were completely dependent on the support of others. Eighteen (5.5%) reported not receiving any support in cleaning their teeth / dentures despite reporting difficulty in doing so. Most of those who were completely dependent (n=145, 83.4%) could not clean their teeth at all. while most (n= 87, 83.7%) of those reporting some difficulty received some support in cleaning their teeth / dentures. Gender and age were not associated with reported difficulty cleaning teeth / dentures (Table 2) whereas type of residence and level of ID were. Table 3 demonstrates initial association between reported difficulty cleaning teeth / dentures and reported problems with teeth or gums, as well as reported dentate status. A lack of oral problems was associated with a lack of difficulty cleaning teeth/dentures. Table 3 about here Frequency of brushing teeth / cleaning dentures The majority (93.1%) of those with teeth or dentures reported having their teeth brushed once or more per day. Similarly, 73.9% of the sample with no teeth or dentures reportedly had their mouth cleaned at least daily. There was no 8 association between reported difficulty in cleaning teeth/dentures and frequency of either brushing teeth or mouth cleaning (Table 5). Regression This model (Table 5) shows that types of residence with increasing dependency, increasing level of ID and the presence of reported oral problems had a significant independent positive effect on reported difficulty cleaning teeth/taking care of dentures. Dentate status did not. This model accounted for only 35.2% of observed variance in whether there was reported difficulty cleaning teeth/taking care of dentures or not, using Cox & Snell R Square. Sensitivity of the model = 69%, specificity of model = 86.6%. Table 5 about here DISCUSSION This study found that most older people with intellectual disabilities in Ireland reported no difficulty carrying out tooth brushing / denture cleaning: 55% of participants reported no difficulty cleaning their teeth / taking care of dentures; 22% reported varying levels of difficulty and 23% could not do it at all. This gives the first nationally representative figures describing reported difficulty cleaning teeth / dentures among older adults with ID, across residential settings. Direct comparison with other research is difficult given differences in geography, population and measurement, regarding difficulty brushing teeth / caring for dentures among people with ID. In one French study, difficulty caring for oral health of people with ID was reported at about 60% in one residential setting (Faulks and Hennequin, 2000). The current study shows that there are distinct levels of difficulty in oral hygiene 9 practices among adults with ID who report some level of difficulty caring for their mouths. Most of those who could not clean their teeth / dentures in the current study were completely dependent on others to carry this out and those reporting some difficulty received support to carry out tooth brushing and care for dentures. Therefore comparison to studies in residential care and community home settings, where between 64 – 72% of adults with ID required assistance brushing/cleaning teeth (or dentures) are meaningful and suggest a higher level of difficulty than that found in our current cross-section (Pradhan et al, 2009a, Stanfield et al., 2003, Crowley et al., 2005). Factors associated with reported difficulty Residential setting and level of intellectual disability were predictive of difficulty brushing/taking care of dentures. Residential setting can be associated with difficulty and frequency of tooth brushing (Pradhan et al., 2009a). In the current study, the majority of people in residential care homes had difficulty brushing their teeth. The opposite was true for those living independently. The proportion reporting difficulty also rose with severity of ID. Age, previously shown to be related to oral hygiene in younger people with ID in certain residential settings only (Tesini, 1980), was not associated with difficulty cleaning teeth or dentures in our study. Reported oral problems were associated with level of difficulty cleaning teeth and dentures in our study. The nature of this correlation is unclear, given the design of the current study. These findings have some interesting implications for those who are interested 10 in improving the oral health of this population. For example, a one-size-fits-all approach to oral health skills training, whereby a uniform intervention is applied to groups of people with ID (Kavvadia et al., 2009) or their carers (Mac Giolla Phadraig et al., 2012), are perhaps inappropriate because a gradient of difficulty is shown to exist within and between residential settings and levels of disability. Stratified approaches using a range of techniques (Kaschke et al., 2005) may be preferred. Those developing oral health programmes for use with populations with ID are likely to come across a range of levels of difficulty brushing teeth and dentures in community care and residential home settings and therefore should design interventions to encompass this range. This means that both residents and carers need a range of skills for dealing with differing levels of difficulty in each setting. In community and residential settings, combinations of independent manual skills for those with no difficulties; training of carers for those completely dependent on care (Mac Giolla Phadraig et al., 2012) and a range of skills for levels of difficulty in between these extremes (British Society for Disability and Oral Health/Faculty of Dental Surgery of Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2012) should be considered, when delivering oral health skills training across these settings. Educators should consider teaching mainly independent manual skills for those living independently or with family. The majority of participants in this study reported daily tooth brushing / mouth cleaning, despite high levels of difficulty and a high need for support,. This is a positive finding and is comparable to reported rates among people with ID in residential services, internationally (Stanfield et al., 2003, Pradhan et al., 2009a, Faulks and Hennequin, 2000). 11 Frequent brushing is not synonymous with effective brushing, which is dependent on other factors such as toothbrush design, toothbrushing techniques, and brushing time (Loe, 2000). Other factors, specifically reported in this population, include irregular changes of toothbrush and failure to purchase toothpaste (Rawlinson, 2001) as well as intellectual and physical impairment (Nunn, 1987), though the true range of factors influencing this are likely to be broad and variable. The current study does not assess if this brushing, which is reportedly frequent, is effective. Given the high levels of disease reported in the population with ID (Glassman and Miller, 2003, Elliot et al., 2005, Anders and Davis, 2010) it is unlikely to be effective – if health is the desired outcome. This suggests, if respondents are accurate, that factors other than frequency are at root cause of ineffective tooth brushing among people with ID. Faulks and colleagues reported that only 40% of staff in one residential service provider in France spent more than one minute cleaning their wards’ teeth (Faulks and Hennequin, 2000), so perhaps time spent brushing warrants attention. This highlights a need to promote not only daily brushing, but effective daily brushing using appropriate technique with individualised support for an adequate length of time. Limitations of this study The major limitation is that data were based on reported behaviours. This introduces the spectre of social desirability bias whereby respondents may wish to give the “correct answer” when responding to some questions (Philips and Clancy, 1972). A design involving direct skills observation as per Glassman and Miller (2006) would have allowed a measure of technique and clinical data would have allowed us to quantify the effectiveness of brushing. Participants 12 responses, in many cases, were completed on behalf of the participants by proxies. Many questions, such as Do you have any obvious problems with your teeth or gums? were answered from the point of view of the proxy and not the participant. This poses a risk of misattribution bias, as seen in other research (Shardell et al., 2013) Conclusions This study showed that people with ID in Ireland reported cleaning their teeth and taking care of their dentures regularly. Many have difficulties brushing their teeth or cleaning their dentures but most do not. Even among those with some difficulty, the exact level of difficulty varied from little difficulty to complete inability. This shows a variable population with variable needs and this evidence can be useful in a number of ways. Firstly it may inform the design of targeted interventions to improve brushing. Factors to consider are level of ID and residential setting. This means that health promotion or educational programmes can be tailored to meet these specific needs based on residential setting and level of ID. Secondly, those planning these programmes need to consider that a range of skills should be taught to carers and those with disabilities. There is a need for further research into the effectiveness of tooth brushing and denture cleaning in this growing population. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge all those who participated in this study and their families and carers. The authors also wish to thank Glaxosmithkline and the Health Research Board, Ireland who provided student scholarships for one author to contribute to this research. 13 References Anders, PL & Davis, EL, 2010. Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Spec Care Dent, 30, 110-7. Bittles, AH, Petterson, BA, Sullivan, SG, Hussain, R, Glasson, EJ & Montgomery, PD. 2002. The influence of intellectual disability on life expectancy. J Gerontol. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 57, M470-2. British Society For Disability And Oral Health/Faculty Of Dental Surgery Of Royal College Of Surgeons Of England. 2012. Clinical guidelines and integrated care pathways for the oral health care of people with learning disabilities [Online]. British Society for Disability and Oral Health. Available: http://www.bsdh.org.uk/guidelines/BSDH_Clinical_Guidelines_PwaLD_2 012.pdf [Accessed 22/01/2013). Connick, C., Palat, M. & Pugliese, S. 2000. The appropriate use of physical restraint: considerations. ASDC J Dent Child, 67, 256-62, 231. Crowley, E., Whelton, H., Murphy, A., Kelleher, V., Cronin, M., Flannery, E. & Nunn, J. 2005. Oral Health of Adults with an Intellectual Disability in Residential Care in Ireland 2003. Department of health and Children Davies, K. W. & Whittle, J. G. 1990. Dental health education: training of homecarers of mentally handicapped adults. Community Dent Health, 7, 193-7. Elliot, I., Nunn, J. & Sadlier, D. 2005. Oral Health & Disability: The way forward. National Disability Authority. Evenhuis, H. M., Hermans, H., Hilgenkamp, T. I., Bastiaanse, L. P. & Echteld, M. A. 2012. Frailty and disability in older adults with intellectual disabilities: results from the healthy ageing and intellectual disability study. J Am Geriatr Soc, 60, 934-8. Faulks, D. & Hennequin, M. 2000. Evaluation of a long-term oral health program by carers of children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Spec Care Dentist, 20, 199-208. Glassman, P. & Miller, C. E. 2003. Preventing dental disease for people with special needs: the need for practical preventive protocols for use in community settings. Spec Care Dentist, 23, 165-7. Kaschke, I., Klaus-Roland, J. & Zeller, A. 2005. The effectiveness of different toothbrushes for people with special needs. J Disab Oral Health, 2, 61-71. Kavvadia, K., Polychronopoulou, A. & Taoufik, K. 2009. Oral hygiene education programme for intellectually impaired students attending a special school. J Disab Oral Health, 10:65-71. Kelly, C. & Kelly, F. 2011. Annual Report of the National Intellectual Disability Database Committee 2010. HRB Statistics Series Dublin: Health Research Board. Kelly, F., Kelly, C., Maguire, G. & Craig, S. 2008. Annual report of the National Intellectual Disability Database Committee 2008. HRB Statistics Series 2. Dublin: Health Research Board. Loe, H. 2000. Oral hygiene in the prevention of caries and periodontal disease. Int Dent J, 50, 129-39. Mac Giolla Phadraig, C., Guerin, S. & Nunn, J. 2012. Train the trainer? A randomized controlled trial of a multi-tiered oral health education 14 programme in community based intellectual disability residential services. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 41:182-92. Mccarron, M., Swinburne, J., Andrews, V., Mcgarvey, B., Murray, M. & Mulryan, N. 2009. Intellectual disability supplement to TILDA: Pilot Report. Dublin: School of Nursing & Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin. Nunn, J. H. 1987. The dental health of mentally and physically handicapped children: a review of the literature. Community Dent Health, 4, 157-68. Owens, P. L., Kerker, B. D., Zigler, E. & Horwitz, S. M. 2006. Vision and oral health needs of individuals with intellectual disability. Ment Retard Dev D R, 12, 28-40. Pradhan, A., Slade, G. D. & Spencer, A. J. 2009a. Access to dental care among adults with physical and intellectual disabilities: residence factors. Aust Dent J, 54, 204-11. Pradhan, A., Slade, G. D. & Spencer, A. J. 2009b. Factors influencing caries experience among adults with physical and intellectual disabilities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol, 37, 143-54. Rawlinson, S. R. 2001. The Dental and Oral Care Needs of Adults with a Learning Disability Living in a Rural Community: Consideration of the Issues. J Intel Dis, 5, 133-156. Shaw, M. J., Shaw, L. & Foster, T. D. 1990. The oral health in different groups of adults with mental handicaps attending Birmingham (UK) adult training centres. Community Dent Health, 7, 135-41. Stanfield, M., Scully, C., Davison, M. F. & Porter, S. 2003. Oral healthcare of clients with learning disability: changes following relocation from hospital to community. B Dent J, 194, 271-7; discussion 262. Tesini, D. A. 1980. Age, degree of mental retardation, institutionalization, and socioeconomic status as determinants in the oral hygiene status of mentally retarded individuals. Community Dent and Oral Epidemiol, 8, 355-9. Van Der Weijden, G. A. & Hioe, K. P. 2005. A systematic review of the effectiveness of self-performed mechanical plaque removal in adults with gingivitis using a manual toothbrush. J Clin Periodontol, 32 Suppl 6, 21428. 15 Table 1: Questions asked to participants of the IDS-TILDA study No. Item Please indicate the level of difficulty, if any, you have with cleaning your Q1 teeth/taking care of your dentures. Q2 Does anyone ever help you to clean your teeth/take care of your dentures? a Q3 How often do you brush your teeth/have them brushed? b Q4 How often do you clean your mouth/ have it cleaned for you? c Q5 Do you have any obvious problems with your teeth or gums? (e.g. painful or sensitive teeth, bleeding gums when you brush your teeth) Q6 Which best describes the teeth you have? a asked of respondents reporting difficulty only b asked of dentate respondents / those reporting denture use only; c asked of edentulous respondents only 16 Table 2 Demographics of sample as a whole and by reported difficulty cleaning teeth / taking care of dentures (valid %) No Some Cannot do p Parameter Total Difficulty difficulty at all Value 753 412 159 172 Total (100%) (55.5%) (21.3%) (23.2%) Gender >0.05 335 189 Male 75 (22.5%) 70(21.0%) (44.9%) (56.6%) 415 223 Female 84 (20.5%) 102(24.9%) (55.1%) (54.5%) >0.05 274 151 40-49 63 (23.3%) 56(20.7%) (36.4%) (55.9%) 344 197 50-64 65 (19.1%) 78 (22.9%) (45.7%) (57.9%) 134 65+ 64 (48.5%) 31 (23.5%) 37 (28.0%) (17.8%) Type of <0.00 Residence 01 Independent 129 111 12 (9.4%) 5 (3.9%) / Family (17.1%) (86.7%) 268 187 Community 54 (20.4%) 24 (9.1%) (35.6%) (70.6%) 356 114 143 Residential 93 (26.6%) (47.3%) (32.3%) (40.9%) <0.00 Level of ID 01 166 145 Mild 15 (9.0%) 6 (3.6%) (23.9%) (87.3%) 323 195 Moderate 85 (26.6%) 40 (12.5%) (46.5%) (60.9%) Severe 206 122 28 (13.9%) 51 (25.4%) / Profound (29.6%) (60.7%) ID = Intellectual Disability; Community = Community Group Home; Residential = Residential Care Home 17 Table 3: Relation of reported dentate status and oral problems with reported difficulty cleaning teeth / taking care of dentures (valid %) No Some Cannot do Parameter Total p Value Difficulty difficulty at all Dentate <0.0001 status 186 91 (48.9%) 29 (15.6%) 66 Edentate (25.1%) (35.5%) 556 320 130 (23.4%) 106 Dentate (74.5%) (57.6%) (19.1%) Reported problemsb Yes No <0.001 160 (21.4%) 589 (78.6%) 68 (43.0%) 47 (29.7%) 341 (58.6%) 112 (19.2%) 43 (27.2%) 129 (22.2%) ex 743; Dentate status = Which best describes the teeth you have? – responses grouped to those with teeth and without; b ex 749; Reported problems = Do you have any obvious problems with your teeth or gums? (e.g. painful or sensitive teeth, bleeding gums when you brush your teeth) a 18 Table 4: The relationship between reported frequency of brushing teeth/cleaning mouth and reported difficulty cleaning teeth/taking care of dentures (valid %) No Some Cannot do p Frequency Total Difficulty difficulty at all Value Tooth brushing a 621 (100%) 369 (59.4%) 138 (22.2%) 114 (18.4%) Once or more a day Less frequently 578 (93.1%) 43 (6.9%) 343 (59.3%) 128 (22.1%) 107 (18.5%) 26 (60.5%) 10 (23.3%) 7 (16.3%) Mouth cleaning b 119 (100%) 42 (35.3%) 20 (16.8%) 57 (47.9%) >0.05 > 0.05 Once or 88 31 (35.2%) 15 (17.0%) 42 (47.7%) more a day (73.9%) Less 31 11 (35.5%) 5 (16.1%) 15 (48.4%) frequently (26.1%) a Tooth brushing = How often do you brush your teeth/have them brushed?; question asked of dentate respondents / edentulous respondents reporting denture use only; b Mouth cleaning = How often do you clean your mouth/have it cleaned for you?; question asked of edentulous respondents without dentures. 19 Table 5. Predictors of difficulty cleaning teeth/taking care of dentures among people with ID B OR CI p value Type of residence Independent/Family 1 Community Group Home 1.813 6.127 (3.21 - 11.694) < 0.001 Residential 1.186 3.276 (2.162 - 4.962) < 0.001 Level of ID Mild 1 Moderate 3.269 26.298 (13.876 - 49.838) < 0.001 Severe / Profound 1.964 7.129 (4.407-11.533) < 0.001 Dentate status Dentate 1 A complete lack of teeth 0.273 1.313 (0.842 - 2.047) 0.229 Obvious problems with mouth or teeth No 1 Yes 0.265 1.303 (1.153 - 1.473) B = Regression coefficient; OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval < 0.001