Disaster, Inc.: Privatization, Marketization, and Post-Katrina Rebuilding

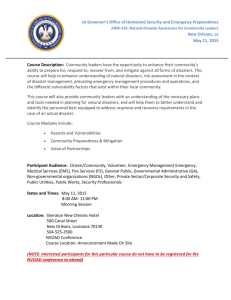

advertisement

1 Disaster, Inc.: Privatization, Marketization, and Post-Katrina Rebuilding Kevin Fox Gotham, Ph.D. Department of Sociology Tulane University 220 Newcomb Hall New Orleans, LA 70118 Email: kgotham@tulane.edu Word Count: 8260 Abstract This paper examines the problems and limitations of the privatization of federal and local disaster recovery policies and services following the Hurricane Katrina disaster. The paper discusses the significance of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 in defunding disaster services; the restructuring of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as a service purchaser and arranger; and the efforts by the New Orleans city government to contract out disaster recovery activities to private firms. On both the federal and local levels, inadequate contract oversight and lack of cost controls provided opportunities for private contractors to siphon public resources and exploit government agencies to further their profiteering interests and accumulation agendas. Finally, I discuss recent shifts toward the "marketization" of the government sector in which private sector logics and modes of operation increasingly penetrate and dominate the operations of the public sector. As this paper illustrates, privatization and marketization have layered new challenges on New Orleans institutions, strained the capacity of the federal government to respond to catastrophes, and portend a future of increasing risk and vulnerability to disaster for New Orleans and U.S. cities. Introduction Recent years have witnessed the growth of a burgeoning literature on the impact and consequences of privatization of government services and public goods. Privatization involves the transfer of ownership of public goods to private organizations or contracting out of government services to private firms. With increasing frequency since the Reagan years, government officials and agencies have applied privatization strategies at the federal, state, and 2 city levels to a wide variety of services, from road maintenance to weapons development to human service provision. Over the last decade, privatization has been occurring in the realms of prisons, public water supplies, public transportation, and military contracting. Scholars such as Setha Low, Dana Taplin, and Suzanne Scheld describe the increasing privatization of public spaces including the sale of public parks and sidewalks to private firms.1 For Low and colleagues, privatization represents a new threat to public space in which patterns of design and private management that exclude some people invariable reduce social and cultural diversity and thereby homogenize community life. Others have focused on the consequence of the proliferation of gated communities and the “mall-ification” of social life where private firms increasingly own and control common public gathering spaces. Craig Calhoun has drawn attention to the recent efforts to privatize risk, to roll back the provision of public goods and restructure government on the basis of private property rights rather than any broader conception of public and communicative rights.2 This paper engages with these debates about the privatization of public resources and government policy in the context post-Katrina New Orleans.3 A variety of government reports have denounced the federal government's response to Hurricane Katrina and called for major reforms in the formulation and implementation of federal disaster policy. Since 1979, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has been the major executive branch agency responsible for organizing and coordinating disaster relief and aid among government agencies, and between government and the private and non-profit sectors. In a report released in February 2009, the Senate Ad Hoc Committee on Disaster Recovery found that "FEMA engaged in an ad hoc response, marred by continually changing requirements, deadlines, and later, litigation that resulted in court ordered reinstatements of previously denied benefits" to needy families and businesses. The subcommittee found "eight fundamental problems" with FEMA's post-Katrina housing response: FEMA had no operational catastrophic disaster plan; FEMA's programs were insufficient to meet housing needs in post-catastrophic events; FEMA decisions to reject other options resulted in heavy reliance on costly trailers and mobile homes; strict legal interpretations of federal laws eliminated housing options and slowed recovery and rebuilding efforts; FEMA's programs were marked by frequent errors; FEMA’s staff was insufficient and poorly trained; FEMA’s policy emphasis on reviving the housing stock of homeowners disadvantaged renters and made it difficult to revitalize rental housing; and flawed FEMA public assistance programs 3 blocked state and local governments from restoring public services needed for housing recovery.4 In this paper, I situate limitations and problems of the federal response to the Hurricane Katrina disaster with reference to longstanding policy trends emphasizing the privatization of public services and resources. I first discuss significance of the Homeland Security Act of 2002 that transferred funds and administration for disaster response from FEMA to other areas of the federal government. Over the last decade, FEMA has increasingly has increasing shifted from an agency that provides resources and services into a role of service purchaser and service arranger. Rather than delivering services, FEMA now finds itself managing contracts and a plethora of networks that stretch from the federal government into state and local governments and the private sector. Next, I discuss the limitations of FEMA's heavy reliance on private contractors, no-bid contracts, and outsourcing during the Hurricane Katrina disaster. I then discuss how the city government’s reliance on private contractors to manage New Orleans's post-Katrina rebuilding program contributed to the fiscal crisis of the state. Finally, I explain the post-Katrina shift to marketization which is the restructuring of government to mimic the features and logic of the private market. While privatization moves an activity into the private sector, marketization refers to a process in which the organizational culture of government is restructured according to market principles. As this paper illustrates, both privatization and marketization have layered new challenges on New Orleans institutions, strained the capacity of governments to respond to catastrophes, and portend a future of increasing risk and vulnerability to disaster for New Orleans and U.S. cities. The Stafford Act and the Historical Development of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) FEMA's statutory authority to respond to disasters derives from the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Act of 1988 (here after referred to as the Stafford Act) that sets procedures for Presidential declaration that a major disaster exists and authorizes assistance for post-disaster redevelopment. The Stafford Act empowers the President to prescribe rules and regulations to implement the provisions of the Act and to delegate authority to any agency to provide federal support and assistance to mitigate severe damage. Once the president declares a disaster, the Stafford Act allows FEMA to "direct any Federal agency, with or without 4 reimbursement, to utilize its authorities and the resources granted to it under Federal law … in support of State and local assistance response and recovery efforts." The Stafford Act also gives broad authority for FEMA to coordinate "all disaster relief assistance (including voluntary assistance) provided by Federal agencies, private organizations, and State and Local governments"5 As the nodal point of the government response system, FEMA directs federal agencies to support state and local assistance efforts; provides technical assistance, advice, and damage and needs assessments with local and state governments; and manages the planning and distribution of federal resources through federal and state government programs, and charities and philanthropic organizations.6 Over the years, the mission and goals of FEMA have been contradictory and unstable, shifting from a focus on "national security" during the 1980s, to a comprehensive all-hazards approach to emergency management in the 1990s, to the development of programs geared toward protecting against terrorist attacks after 2001. In adopting the view that "all disasters are local," the 1974 Disaster Relief Act made clear that state and local governments were responsible for planning and responding to disasters, a policy orientation that devolved decision making to states while retaining federal funding functions. The establishment of FEMA in 1979 expressed the Carter Administration's desire to shrink "big government" by merging disparate disaster functions in one agency. The federal government charged FEMA with establishing an integrated emergency management system to replace the patchwork of disparate agencies, socio-legal regulations, and executive orders pertaining to crisis and disaster management.7 During the 1980s, FEMA became a source of patronage jobs for political appointees of the Reagan and Bush Administrations while the Clinton Administration attempted to professionalize FEMA but without changing federal devolution goals and prerogatives. The Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 clarified that state and local governments were "first responders" in all disasters.8 FEMA’s poor response to Hurricane Hugo and the Loma Prieta Earthquake in 1989 and Hurricane Andrew in 1992 brought intense political scrutiny and spurred Congress to launch several investigates into the agency's policy failures. Five days after Hugo, federal officials had not provided food and water to the rural poor in towns such as St. Stephen and Ridgeville, outside Charleston. FEMA took ten days to open a disaster center in Berkeley County, South Carolina. Nine months after Hugo, approximately 1,200 families in South Carolina still needed 5 assistance. Disaster victims and public officials in the Carolinas assailed FEMA’s response. Senator Ernest F. Hollings (D-SC) called FEMA’s staff “the sorriest bunch of bureaucratic jackasses I’ve ever known.”9 Frustrated by FEMA's sluggish response to the Loma Prieta Earthquake, Congressman Norman Mineta (D-CA), concluded that the agency "could screw up a two-car parade.”10 Pete Stark (D-CA) derided the agency for its ''Keystone Kops" performance during the Loma Prieta earthquake and Hurricane Hugo, and attributed the agency’s poor performance to its “becoming a turkey farm for flunkies and political supporters.”11 The agency's lackluster response to Hurricane Andrew drew the ire of hurricane victims who posted signs saying, “What do George Bush and Hurricane Andrew have in common? They’re both natural disasters.”12 Some members of Congress proposed eliminating FEMA altogether.13 During these years, elected officials and government reports complained about FEMA’s vague mission and unclear legislative charter, lack of regulatory authority and mandating ability, small budget and grant-issuance power, and weak management systems. Vacillating political support for disaster management complicated and strained efforts to strengthen disaster mitigation capacities between the federal agencies and state, and local governments. 14 A 1993 GAO report observed that FEMA was supposed to “emphasize hazard mitigation and state and local preparedness, thereby minimizing the need for federal intervention."15 "The time has come to shift the emphasis from national security to domestic emergency management using allhazards approach,” declared The National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) in 1993.16 Following the recommendations of the NAPA study, President Clinton reorganized FEMA with a focus on mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery from all hazards. This shift in focus from national security concerns to all disasters reflected Clinton's interest on "reinventing government" with "a more anticipatory and customer-driven response to catastrophic disasters."17 President Clinton elevated FEMA to cabinet status and appointed James Witt to direct the agency. Witt professionalized FEMA by reducing the number of appointees and hiring trained emergency and disaster specialists. Witt deemphasized civil defense and created a Mitigation Directorate in 1994 and, in 1997, a cooperative project with local governments called Project Impact. During the Clinton years, Witt increased resources for disaster mitigation, response, and recovery and used grants to build relationships between FEMA and state and local emergency service providers to encourage state and local disaster preparation. According to one review of the period, “…‘all hazards’ became a mantra that, when combined 6 with organizational changes, turned FEMA into a streamlined, professional natural disasters preparation and response clearinghouse.”18 During the Midwest floods of 1993, the New York Times reported in a series of short interviews with disaster victims at a few aid locations in Missouri that not one was critical of FEMA's response. The article went on to say, “By almost every measure, Mr. Witt’s early performance managing the flood response is being received well by flood survivors, local officials and members of the agency staff.”19 The George W. Bush Administration inaugurated a new era of federal disaster management defined by the policy priorities of defunding and deregulation. In its first budget, the Bush Administration proposed cutting $200 million from FEMA’s budget, primarily in mitigation activities, and eliminating Project Impact, a hazard mitigation program started during the Clinton administration to provide grants to cities to make communities more resilient.20 In response to the proposed cuts, Peter La Porte, Director of the National Emergency Management Association (NEMA) for the District of Columbia, appeared before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, State, and the Judiciary to advocate for a renewed focus on disaster mitigation: I cannot hesitate to mention that with all of the changes and new responsibilities placed on FEMA … NEMA remains extremely concerned about the federal budget cuts to FEMA. Specifically, we are concerned about the lack of pre-disaster mitigation funding as authorized by the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 and the change in the federal-state cost-share for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program from 75/25 to 50/50. States are spending more than ever on emergency management and now faced with new threats, funding is of primary concern. These cuts to FEMA only make the point stronger that mitigation includes terrorism preparedness and that FEMA needs the resources to follow through on the missions of the organization, whether they are existing programs or brand new programs.21 White House spokesman Scott Stanzel explained that proposed cuts to these federal emergency management programs were part of “an ongoing effort to shift control and responsibility to the states and give them more flexibility.”22 As George Bush's Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Director, Mitch Daniels, stated at a conference in March 2001, "the general idea - that the business of government is not to provide services, but to make sure 7 that they are provided - seems self-evident to me." Joe Allbaugh, President George W. Bush’s first FEMA director, expressed the Administration’s interest in devolving disaster mitigation and assistance in his May 2001 testimony before a Senate Appropriations subcommittee: Disaster mitigation and prevention activities are inherently grassroots … [W]e are giving more control to State and local governments … [W]e are asking that they take a more appropriate degree of fiscal responsibility to protect themselves. The original intent of Federal disaster assistance is to supplement State and local response efforts. Many are concerned that Federal disaster assistance may have evolved into both an oversized entitlement program and a disincentive to effective State and local risk management. Expectations of when the Federal Government should be involved and the degree of involvement may have ballooned beyond what is an appropriate level. We must restore the predominant role of State and local response to most disasters. Federal assistance needs to supplement, not supplant, State and local efforts.23 The Bush Administration's emphasis on devolution and defunding projected highly ambiguous and contradictory views on the value of mitigation and crisis response. On the one hand, elected leaders championed a strong federal government security system to prevent terrorist attacks and other threats to national security. On the other hand, many fiscal conservatives argued that FEMA had become a symptomatic of “big government” and believed that disaster declarations had become a form of pork-barrel spending. During the Midwest flood of May 2001, for example, Allbaugh chastised residents of Davenport, Iowa for not doing enough to prevent flooding in the midst of massive federal recovery efforts. According to Allbaugh, "how many times will the American taxpayer have to step in and take care of this flooding, which could be easily prevented by building levees and dikes?"24 A month later, the Washington Post reported that the Bush administration's moves against mitigation programs were causing worries in disaster-prone states. "Statehouse critics of the proposed cuts contend that in the long run they would cost the government more because many communities will be unable to afford preventative measures and as a result will require more relief money when disasters strike," the newspaper noted. 25 The events of September 11, 2001 and the subsequent creation of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) accelerated efforts to devolve federal disaster response programs and 8 force local governments to assume a greater financial responsibility in mitigating the effects of natural calamities. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 moved 22 federal agencies and 170,000 federal employees under the control of the DHS. The Act eliminated the cabinet-level status of FEMA and separated national security and natural disaster response and recovery missions. The Executive Branch and the DHS minimized FEMA's all-hazards, comprehensive approach on preparing for and responding to all types of disasters by redefining the mission of the agency as one of responding to terrorist attacks. After DHS absorbed FEMA, three-fourths of every grant dollar provided by FEMA for local preparedness and first-responders went to terrorism-related measures - in other words, $2 billion in grants to prevent terrorist attacks, but initially, only $180 million for natural disasters.26 In addition, FEMA's incorporation into the DHS resulted in a reallocation of more than $800 million in federal grant money for state emergency management offices to state homeland security offices for use in counterterrorism from 2001 to 2005.27 Additionally, by moving into the DHS, FEMA lost its bureaucratic autonomy and was now a small agency of approximately 2,500 employees competing for resources within a massive department of over 170,000 employees. Congressional leaders and state- and local-level organizations representing emergencyresponse agencies protested against funding shortages and FEMA’s shift away from preparing for natural disasters. The new emphasis on preparing for and responding to terrorist attacks alarmed elected officials who feared that FEMA’s autonomy and mission were being compromised by the Homeland Security legislation. During the Senate debate on the creation of the DHS, U.S. Senator Jim Jeffords complained that [w]ith the passage of this Homeland Security legislation, we will destroy the Federal Emergency Management Agency, losing years of progress toward a well-coordinated Federal response to disasters. As it now exists, FEMA is a lean, flexible agency receiving bipartisan praise as one of the most effective agencies in government … I cannot understand why, after years of frustration and failure, we would jeopardize the Federal government's effective response to natural disasters by dissolving FEMA into this monolithic Homeland Security Department. I fear that FEMA will no longer be able to adequately respond to hurricanes, fires, floods, and earthquakes, begging the question, who will?28 9 Over the next several years, organizations representing emergency management specialists, state and local officials, and disaster mitigation researchers decried the draconian budget cuts affecting disaster preparedness and response capacities. In April 2005, the International Association of Emergency Managers noted that state and local emergency management programs were in "desperate need" of federal funding to meet new standards. A month later, however, Bush's fiscal 2006 budget proposed a 6 percent cut in funding for Emergency Management Performance Grants, from the $180 million appropriated by Congress in 2005 to $170 million in 2006. State and local officials protested what they saw as White House cuts targeting the very program that would help them meet Bush's new disasterpreparedness goals. "The grants are the lifeblood for local programs and, in some cases, it's the difference between having a program in a county and not," noted Dewayne West, the director of Emergency Services for Johnston County, North Carolina, and president of the International Association of Emergency Managers.29 Several months later, in July 2005, the National Emergency Management Association wrote lawmakers expressing "grave" concern that still-pending changes proposed at the DHS would undercut FEMA. "Our primary concern relates to the total lack of focus on naturalhazards preparedness," David Liebersbach, the association's president, said in the July 27 letter to Sens. Susan Collins and Joseph Lieberman, the leaders of a key Senate committee overseeing the agency. Lierbersbach contended that emphasis on terrorism "indicates that FEMA's longstanding mission of preparedness for all types of disasters has been forgotten at DHS." According to a Congressional Research Service report, President Bush proposed $3.36 billion for state and local homeland-security assistance programs for fiscal year 2006, $250 million less than these programs received from Congress in 2005.30 According to the Homeland Security inspector general, nearly three-fourths of federal Homeland Security grants went to three terrorism-focused programs. Funds for "all-hazards" fell from $1 billion in 2004 to $720 million, while those aimed at terrorism rose from $130 million to $2.6 billion.31 In short, FEMA underwent a dramatic and intense transformation in the years after the September 11 disaster. As figure 1 shows, Organizational changes caused considerable flux in FEMA’s resources from fiscal years 2001 through 2005. Changes in FEMA’s structure and responsibilities occurred multiple times in this period. FEMA underwent several reorganizations 10 in fiscal years 2001 and 2002, but the most significant change occurred in March 2003 when FEMA transitioned from an independent agency to a component of the newly created DHS. The incorporation of FEMA into the DHS shifted resources away from disaster response and mitigation and created a new situation where the agency was subject to greater external fiscal constraints and bureaucratic control. Funds to staff, manage, and operate FEMA programs and day-to-day operations now had to compete with other Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and federal priorities for limited resources. The decline in resources and increased dependence limited autonomy and exacerbated fiscal uncertainty, both of which threatened FEMA's capacity to plan and respond to disasters. FIGURE 1 HERE Privatizing Federal Disaster Aid: The Role of Multinational Corporations Hurricane Katrina provided the first major test of the newly established Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that executive branch officials and managers designed to make the nation safer and more secure against terrorist strikes and other disasters. Funding cuts for disaster mitigation and training coupled with organizational redefinition and change eroded FEMA’s capacity to coordinate government response and deliver resources to disaster-impacted communities. FEMA's resources were not sufficient to coordinate a massive and urgent logistical effort without substantial assistance. As a result, a distinctive feature of the federal government’s response to the devastation caused by the levee breaches was the heavy reliance on no-bid contracts, outsourcing, and use of large private corporations to meet the recovery needs of governments and displaced residents. In the weeks following the levee breaks, FEMA entered into no-bid contracts with four multinational corporations - Fluor Enterprises, Inc. (Fluor), Shaw Group (Shaw), CH2M Hill Constructors, Inc. (Hill), and Bechtel National, Inc. (Bechtel). These contracts tasked the firms to provide and coordinate project management services for temporary housing. FEMA even had to hire a contractor to award contracts to contractors.32 One of the limitations of this privatized system of disaster response was the federal government's execution of these initial contracts on the basis of pre-award authorization without pre-award audits or defined statements of work. As of early December 2006, FEMA had obligated approximately $3.2 billion to Individual Assistance – Technical Assistance Contracts (IA-TAC) organized by multinational corporations for hurricane relief. These contracts included $1.3 billion for Fluor, $830 million for Shaw, $464 million for Hill, and $517 million for Bechtel 11 (see Table #1). The government entered into contractual arrangements to reimburse the firms for funds they spent without defining the terms and conditions associated with a contract or task order. In January 2006, FEMA conducted an assessment and identified several problems with the use of private contractors including, in some cases, “contractors have invoiced the government for the cost of services in excess of the allowable level of reimbursement permitted.” During this time, FEMA officials lamented the escalating dollar amounts for the contacts, noting that that all the contracts were nearing their ceilings. At the time of the January 2006 assessment, the ceiling for each of the four contracts had been raised to $500 million. FEMA estimated that the ceilings on three of the four contracts would need to be raised even higher to complete the work assigned. FEMA officials complained that the agency had too few contract management personal to sustain the workload’; staffing levels were “fluctuating greatly”; and the agency had “little ability to plan and project accurate staffing levels.” FEMA officials also expressed concern that “high turnover is hurting effectiveness, frustrating staff, housing managers and contractors”33 TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE FEMA correspondence suggests that the contract ceiling issue posed a serious threat to the New Orleans recovery operation. In January 2006, two of the four contractors, Shaw and Flour, threatened to cease disaster-related recovery operations if FEMA did not raise the $500 million ceilings. In a February 2006 email, officials with the Shaw Corporation noted that the firm "will have to shut down in 4-5 weeks without a ceiling increase." During the same time, Flour complained of "potential demobilization due to contract ceiling amount." Flour noted "the citizens of Louisiana will have to suffer even more if we are forced to demobilize" and warned "delay before another contract is mobilized and in place ready to respond." A month later, in March 2006, FEMA raised the Fluor ceiling to over $1 billion and the Shaw ceiling to $950 million. Work continued to be tasked to these contractors without FEMA performing cost estimates and negotiating prices. As Figure #1 shows, funding increased dramatically from September 2005 to August 2006.34 FIGURE 2 HERE FEMA's response to the Hurricane Katrina disaster reflected and reinforced trends toward the privatization and outsourcing of federal disaster aid. In 2008, FEMA began outsourcing of much of the agency's logistics to private contractors who are now in charge of acquiring, storing 12 and moving emergency supplies. This arrangement, known as third-party logistics, reflects the agency's perception that the private sector is better equipped to deliver resources and plan for disasters. The federal level privatization of disaster provisions dovetails with state-level attempts to contract out emergency management operations to large retailers such as Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and other companies to provide waster, ice, and critical supplies during crises. After seeing the sluggish response to Hurricane Katrina, the state of Texas established their own emergency management division to plan for catastrophes and provide disaster aid when needed, the assumption being that FEMA will provide nothing. If they can get supplies that way, a FEMA spokesperson told the Houston Chronicle, "that's just one last thing we don't have to coordinate for."35 While the motivation for FEMA's realigned logistics program has been to reduce costs, a major outcome has been the growth of a new market of entrepreneurs and firms that now view disasters as major money-making opportunities. Thus, privatization expresses the growth of what Naomi Klein has called the "disaster-capitalism complex" in which disasters themselves have become major new markets and sources of corporate and investment. Privatizing Disaster Recovery Services: The Role of the Local State Since the Hurricane Katrina roared ashore, the city governments throughout the Gulf Coast have relied heavily on funding from the FEMA Public Assistance Program to repair and rebuild their storm damaged streets and facilities. Unlike other types of federal grant programs, FEMA Public Assistance is a cost reimbursement program that covers costs to complete eligible work. To be eligible for reimbursement, work must be necessary to repair damages that are the direct result of a declared disaster. To ensure that costs are reasonable, FEMA rules require competitive procurement of contracts, as well as contract terms and contract management practices that keep costs under control. In December 2007, the City of New Orleans awarded a one-year contract worth $150,000 to MWH Americas, Inc. (MWH) to manage the City’s program for repair and rehabilitation of City-owned buildings, facilities, and streets. The contract initially encompassed approximately 150 projects with a total estimated design and construction cost of $450 million to $600 million. Over the next two years, the City amended and expanded the contract to authorize MWH to provide “staff augmentation” services to “various City departments” and authorized the use of 13 over $7 million in federal Community Development Block Grant funds to compensate MWH. By December 2009, the City estimated the contract to be worth up to $48 million dollars. Through this contracting arrangement, the City privatized major responsibility for managing the local government’s rebuilding program. Early on, the City transferred dozens of city management functions in the Chief Administrative Officer’s Capital Projects Administration for building projects and in the Department of Public Works for street projects to MWH employees or subcontractors. Through this privatization operation, the City tasked MWH employees and subcontractors with developing administrative practices for the City, including project planning, procurement, and contract management. From 2007 through 2009, the privatization of rebuilding programs placed huge burdens on the City to maintain control over the work and the cost of the programs as well as MWH's fees. An evaluation by the New Orleans Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that "the contract terms negotiated by the City did not provide appropriate controls or incentives to contain costs and that City contract oversight was inadequate to protect against excessive fees and inappropriate charges. The City’s RFP process, which allowed MWH’s proposal for a $150,000 scope of work to mushroom into a contract worth hundreds of times that amount, nullified any meaningful competition for the contract." This same report noted that the "contract oversight was inadequate to protect against excessive fees and inappropriate charges" and lacked meaningful competition.36 In addition, the OIG investigation found that MWH refused to provide evidence that it was honoring its contractual obligation to charge the city its "most favored customer rates"; "the city improperly paid MWH for work performed prior to the execution of the contract" (p. 15); "the contract did not require MWH to assign key personnel to the infrastructure project" (p. 16); "the contract calls for MWH to be paid on a time and materials basis, a form of compensation that presents a high risk of excessive charges" (p. 17); "the contract calls for MWH to be paid for expenses on a cost-plus-percentage-of-cost basis, a form of compensation that is specifically prohibited under FEMA rules" (p. 18); "the not-to-exceed contract cost was not based on a realistic budget for the infrastructure project"; "MWH’s billings for capital projects provide no basis for allocating costs to specific projects or for keeping MWH’s fees in line with overall project costs" (p. 20); "the city allowed MWH’s fees to mount faster than the rate of progress on capital projects" (p. 22); "the state revolving fund has been partially depleted to expedite payments to MWH without regard for whether expenditures will be reimbursed" (p. 23); "the 14 city paid MWH $1,309,572 for unspecified expenses during the first 18 months of the contract" (p. 24); "MWH employees sought reimbursement from MWH for gifts to city employees and elected officials" (p. 25).37 Another example of the privatization of disaster rebuilding was the City's decision to use MWH in "piggyback contracting" which involves expanding an existing contract by adding on additional services. FEMA forbids this practice because it is noncompetitive and does not ensure reasonable prices for work performed. Two examples are relevant. First, in February 2009, the City awarded MWH a contract to advise and assist with FEMA policies, reimbursements, and practices. In turn, MWH subcontracted out the FEMA consultant services to Integrated Disaster Solutions (IDS). In the five-month period from February 2009 through June 2009, MWH billed the City more than $640,000 for services provided by IDS even though MWH played no role in directing or supervising the work. Second, in June 2009, the City directed MWH to enter into a contract with Wink Design Group, LLC (WDG), an architectural firm, to prepare a facility condition assessment report for the Chevron Building. The City paid MWH $187,640 for this assessment in connection as part of a proposed plan to purchase the property for a new City Hall. There is no evidence that the services procured through these extensions to the MWH contract were advertised or subjected to public scrutiny.38 In both of these examples, the City used the MWH Contract as a vehicle for procuring other professional services that circumvented both normal channels of public scrutiny and FEMA’s requirement for competitive procurement of services. The problems of escalating and excessive costs, lack of oversight and accountability, and explicit rule violations plagued other city contracts to manage the disaster recovery program. In December 2006, the City signed a one-year contract with Disaster Recovery Consultants, LLC (DRC) to assist with FEMA claims for damages caused by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The City’s initial contract with DRC included a maximum compensation amount of $600,000. Over the next few years, this contract was amended eight times, extending the term through December 31, 2010, and increasing the maximum compensation to $7,350,00. Important, the contract terms included no specification of timetable of completion, deliverables, or system for tracking DRC’s progress. Like the contract with MWH, the City expanded the DRC Contract by Adding Services that were unrelated to FEMA Public Assistance. These services include processing real estate tax bills, reconciling IRS tax deposits, and other accounting and audit functions that have 15 little or no relationship to the FEMA reimbursement process. An OIG investigation of this contract found that the “City failed to include contract terms to ensure accountability or to exercise effective oversight … The City did not attempt to determine whether the services needed could be obtained more cost-effectively through another contract or by using City employees before extending the contract."39 In addition to the MWH and DRC contacts, the City currently has at least three other contractors whose scope of work includes managing some aspect of the FEMA reimbursement process. These contracts include overlapping responsibilities, duplications of efforts, and no effective oversight procedures to hold contractors accountable for the cost of or results produced by their services. The City has continued to extend their contracts with private firms without evaluating efficiency, or the cost-effectiveness of contracting out as a vehicle to staff City departments performing non-FEMA related functions. As one Times Picayune newspaper article from May 2010 noted, It's long been a mystery how much the city spends on private vendors, largely because city budget documents generally do not list contracts as line items. But the fact that private vendors have supplanted civil servants in performing many basic government functions became clear in recent years as contractors and subcontractors, especially in the areas of technology and recovery, moved into city offices -- and sometimes even handed out city business cards.40 Overall, the City's decision to contract out for FEMA Public Assistance expertise and privatize the capital repair program contributed to the post-disaster fiscal crisis as contract oversight was inadequate to protect against excessive fees and inappropriate charges. As of August 2010, New Orleans was running a deficit of $67.5 million. On July 29, 2010, Mayor Mitch Landrieu announced a package of spending cuts to compensate for falling revenue amid the ominous deficit. Other actions to address the fiscal crisis include reducing overtime, renegotiating contracts, cutting pension payments, laying off some Police Department personnel, using $23 million in one-time money from an insurance settlement, and requiring almost all city workers to take 11 unpaid furlough days during the final five months of the year. 41 In short, rather than alleviating the financial problems of city government, privatization has exacerbated the fiscal crisis of the local state. 16 Conclusion: From Privatization to Marketization Since the Hurricane Katrina disaster, the renewed interest in privatization has layered new challenges on New Orleans institutions and efforts are underway to restructure city government following the competitive logics of the private market. In an effort to combat the fiscal crisis and reduce costs, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu is adopting a more businesslike approach to city operations. The mayor has pushed city agencies to adopt new performance standards to promote consistency and cost-effectiveness. Messages about cost-containment are paired with the promotion of a new public-private partnership, the NOLA Business Alliance, to create and implement a business growth and retention plan for the city. Created in August 2010, the NOLA Business Alliance is governed by a 17-member board with seven people from the public sector, seven from the private sector, and three from nongovernmental organizations. “This is a landmark step for our city,” said Mayor Landrieu. “For the first time, both the public and private sector will partner in a single coordinated effort to deliver new jobs and economic opportunities for this city. And we will facilitate economic growth by linking government, the private sector and the nonprofit sector while leveraging our resources. It’s another step in our goal to restructure and transform city government by implementing best practices that improve our quality of life.”42 Mayor Landrieu’s comments express a broad shift toward the “marketzation" of city government in which the culture and activities of local government are being restructured according to market principles. Whereas privatization involves the relocation of public activities and government activities to the private sector, marketization is the application of competitive logics and market-style mechanisms to the public sector. Examples of marketization include the creation of public-private partnerships, agency franchises, government corporations, and competitive sourcing. In New Orleans and elsewhere, city elites and elected officials now view business-like procedures as essential for reducing costs, maximizing success, and promoting community vitality. Yet both privatization and marketization are associated with a series of contradictions including the blurring of policy responsibilities among the public and private sectors, the production of fiscal crisis, increase in risk and disaster vulnerability due the promotion of a "growth-first" approach to urban redevelopment, and the growth rather than diminution of state power. 17 Interesting, neither privatization nor marketization involve the withdrawal or downsizing of government. Rather these two processes depend on the creation of new modes of expanded state intervention in the form of rules, laws, and policies to stimulate private investment and compensate for the failures and negative consequences of private sector action. On the one hand, privatization is associated with an expansion of the state because state policies and statutes provide the socio-legal regulations to create and enforce market transactions between the public and private sectors. On the other hand, privatization necessitates state action to manage the inevitable problems of unregulated privatization. In response to the problems with city contracts with DRC and MWH, the New Orleans city government has created an Office of Inspector General, a new layer of public bureaucracy, to evaluate and oversee the privatization of disaster services that has occurred since the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Overall, privatization and marketization discourses have popular appeal and elected officials throughout the United States have embraced strategies of outsourcing and contracting out as expedients to revitalizing their cities and economies. As cities and states grapple with the recession and search for the best methods to alleviate economic and budgetary pressures, some lawmakers continue to propose privatization as an effective policy. Over the last few years, there have been proposals to privatize functions across the board: county zoos, libraries, custodial services, parking enforcement, youth shelters, group homes, ambulance services, airports, and transit networks. The lure is the supposed promise that privatization will deliver a short-term budget fix. Rather than reducing costs and optimizing the delivery of disaster services, however, privatization has exacerbated the fiscal crisis of the local state and reduced democratic accountability. Many privatization efforts, including the example of post-Katrina disaster policy, have cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars and botched services for the public. That privatization continues to move forward despite such a poor track record reflects the power of market-centered ideology that assumes that the private market delivers the most efficient outcomes, even without demonstrable results. Some states may also be making the more cynical decision to pursue immediate short-term infusions of capital at the expense of longterm financial cost in pursuit of short-term electoral gains. In any case, privatization comes at the expense of long-term investments in the community, sustainable budget policy, and public accountability. 18 Figure 1: Changes in Programs and Funding for FEMA, March 1 2003 – 2005 (fiscal year) (in Millions of Dollars) Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) FEMA (moved to DHS in 2003) Program moved into FEMA FEMA Programs that transferred into Other entities in DHS Program moved back to HHS Emergency Management Performance Grant $163.9 National Stockpile $429 Fire Grants Program $745 Public Health Programs $34 Metropolitan Medical Response System (MMRS) $50 Inspector General $13.9 Program moved into FEMA Citizens Corps (created in 2003) $ 20 Grants for Emergency Management (created in 2003) $70 Program moved into FEMA Program moved to DHS Programs moved to DHS Source: Government Accountability Office (GAO). January 2007. Budget Issues: FEMA Needs Adequate Data, Plans, and Systems to Effectively Manage Resources for Day-to-Day Operations. GAO-07-139. 19 20 Table 1: FEMA Contract Obligations for Hurricane Katrina, 2005-2006 Percentage of Total Percentage of IA-TAC Contract Contract Obligations Total Total FEMA Contract Obligations $10.8 Billion Other Obligations $7.5 Billion 70% IA-TAC Contract Obligations $3.2 Billion 30% Fluor $1.3 Billion 12% 43% Shaw $830 Million 7.7% 26% Bechtel $517 Million 4.8% 16% Hill $63 Million 15% 0.6% IA-TAC stands for "Individual Assistance – Technical Assistance Contract" Source: Williams, Adley and Company, LLP analysis of IA-TAC Task Order Summary December 2006, provided by FEMA. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General. August 2008. Hurricane Katrina Temporary Housing Technical Assistance Contracts. OIG 88-08. Pp. 2-3. 21 Figure 2: Funding Increase for FEMA IA-TAC Contracts for Hurricane Katrina, September 2005 – September 2006 $2500 * $2000 * * Jul Aug * Amount in Millions $1500 * * * $1000 * $500 * * Dec Jan 2006 * * $0 * Sept 2005 Oct Nov Feb IA-TAC stands for "Individual Assistance – Technical Assistance Contract" Mar Apr May Jun Sept 22 Source: Williams, Adley and Company, LLP analysis of IA-TAC Task Order Summary December 2006, provided by FEMA. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General. August 2008. Hurricane Katrina Temporary Housing Technical Assistance Contracts. OIG 88-08. Pp. 2-3. 23 ENDNOTES 1 Low, Setha, Dana Taplin, and Suzanne Scheld 2005. Rethinking Urban Parks. Public Space and Cultural Diversity. University of Texas Press. 2 Calhoun., Craig. 2010. "Privatization of Risk." http://privatizationofrisk.ssrc.org/ 3 Hurricane Katrina triggered the collapse of the Army Corps of Engineers' levees flooding approximately 80 percent of the city of New Orleans and all of St. Bernard Parish. The deluge caused 1464 deaths and estimated damages at approximately $150 billion. In New Orleans alone, 134,000 housing units – 70% of all occupied units – suffered damage from Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent flooding. The storm displaced more than a million people in the Gulf Coast region. The population of New Orleans fell from 455,188 before Katrina (July 2005) to 208,548 after Katrina (July 2006) – a decrease of 246,640 people and a loss of over half of the city’s population. Of the $120.5 billion in federal spending, the majority – approximately $75 billion – went to emergency relief rather than long-term rebuilding (Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. 2010. "Facts for Features: Hurricane Katrina Impact." http://www.gnocdc.org/Factsforfeatures/HurricaneKatrinaImpact/HurricaneKatrinaImpact.pdf) 4 See pp. 5,12 in United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery. 2009. Far From Home: Deficiencies in Federal Disaster Housing Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and Recommendations for Improvement: Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 5 quotes from the Stafford Act appear in p. 38 United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery. 2009. Far From Home: Deficiencies in Federal Disaster Housing Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and Recommendations for Improvement: Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office (emphasis in original). 6 Stehr, Steven D. 2006. The Political Economy of Urban Disaster Assistance." Urban Affairs Review. Vol. 41, No. 4, March 2006 492-500; Morris, John C. 2006. "Whither FEMA? Hurricane Katrina and FEMA’s Response to the Gulf Coast." Public Works Management and Policy, Vol. 10 No. 4, April 2006, pp. 284-294; Moss, Mitchell Moss, Charles Schellhamer, and David A. Berman. 2009. " The Stafford Act and Priorities for Reform." Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. Volume 6, Issue 1. Pp. 1-21. 7 Haddow, George D., Jane A. Bullock, and Damon P. Coppola. 2007. Introduction to emergency management. 3rd ed. Boston: Elsevier; Wamsley, Gary L., and Aaron D. Schroeder. 1996. Escalating the Quagmire: The Changing Dynamics of the Emergency Management Policy Subsystem. Public Administration Review 56(3): 235-44; Wamsley, Gary L., Aaron D. Schroeder, and Larry M. Lane. 1996. To Politicize is Not to Control: The Pathologies of Control in the Federal Emergency Management Agency. American Review of Public Administration 26(3):263-85. 24 8 For overviews of the historical development of FEMA, see Lewis, David E. "FEMA's Politicization and the Road to Katrina." Working Paper. Princeton University. http://people.vanderbilt.edu/~david.lewis/Papers/PoliticizationPerformance0607.pdf (accessed March 30, 2010). Roberts, Patrick S. 2006. "FEMA and the Prospects for Reputation-Based Autonomy." Studies in American Political Development 20 (Spring):57-87; Haddow, George D., Jane A. Bullock, and Damon P. Coppola. 2007. Introduction to emergency management. 3rd ed. Boston: Elsevier; Wamsley, Gary L., and Aaron D. Schroeder. 1996. Escalating the Quagmire: The Changing Dynamics of the Emergency Management Policy Subsystem. Public Administration Review 56(3): 235-44; Wamsley, Gary L., Aaron D. Schroeder, and Larry M. Lane. 1996. To Politicize is Not to Control: The Pathologies of Control in the Federal Emergency Management Agency. American Review of Public Administration 26(3):263-85. 9 Barr, Stephen. January 19, 2001. "One Reason FEMA Is No Longer a Disaster Area." Washington Post Mathews, Jay. 1990. “Quake Leaves Frustration in Bay Area.” Washington Post, April 17, 1990, A4. 10 Claiborne, William. 1993. “ ‘Culture’ Being Clubbed; Mikulski, Witt Intend to Shake Up FEMA.” Washington Post, May 20, 1993, A21; U.S. House 1992, 541. 11 Lochhead, Carolyn. 1993. “Pete Stark Withdraws House Bill to End FEMA.” San Francisco Chronicle, September 16, 1993, A8. 12 13 Sylves, Richard T. 1994. Ferment at FEMA: Reforming Emergency Management. Public Administration Review 54(3):303-7. 14 National Academy of Public Administration. 1993. Coping with Catastrophe: Building an Emergency Management System that Meets People’s Needs in Natural and Manmade Disasters. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration, February 1993. 15 p. 303 Sylves, Richard T. 1994. Ferment at FEMA: Reforming Emergency Management. Public Administration Review 54(3):303-7. 16 National Academy of Public Administration. 1993. Coping with Catastrophe: Building an Emergency Management System that Meets People’s Needs in Natural and Manmade Disasters. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration, February 1993. 17 See chapter two in Cooper, Christopher, and Robert Block. 2006. Disaster: Hurricane Katrina and the Failure of Homeland Security. New York, NY: Times Books. 18 P. 69 in Roberts, Patrick S. 2006. FEMA and the Prospects for Reputation-Based Autonomy. Studies in American Political Development 20 (Spring):57-87. Schneider, Keith. 1993. “In this Emergency, Agency Wins Praise for its Response.” New York Times, July 20, 1993, A12. 19 25 20 P. 497 in Stehr, Steven D. 2006. The Political Economy of Urban Disaster Assistance." Urban Affairs Review. Vol. 41, No. 4, March 2006 492-500; See chapter 1 in Anrig, Greg. 2007. Conservatives Have No Clothes: Why Right-Wing Ideas Keep Failing. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 21 Statement of Peter La Porte, Director of Emergency Management for the District of Columbia, appeared before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, State, and the Judiciary. May 10, 2001. http://bioterrorism.slu.edu/bt/official/congress/may102001_02_p.htm (accessed March 29, 2010. 22 Claiborne, William. May 8, 2001. "Disaster Management Cuts Raise Concerns: Some States Fear Bush's Budget Actions on Preparedness May Signal Policy Shift." Washington Post. P.A21. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). 2007 “Testimony of Federal Emergency Management Agency Director Joe M. Allbaugh.” http://www.fema.gov/about/director/allbaugh/testimony/051601.shtm (Accessed March 29, 2010). 23 Claiborne, William. 2001. “At FEMA, Allbaugh’s New Order; Ex-Bush Campaign Head Brings Hands-On Managerial Style.” Washington Post, June 4, 2001, A17. 24 25 Claiborne, William. May 8, 2001. "Disaster Management Cuts Raise Concerns: Some States Fear Bush's Budget Actions on Preparedness May Signal Policy Shift." Washington Post. P.A21. Gosselin, Peter and Miller, Alan. September 5, 2005. “Why FEMA Was Missing in Action.” Los Angeles Times; http://articles.latimes.com/2005/sep/05/nation/na-fema5 (accessed March 29, 2010); Manjoo, Farhad. September 7, 2005. “Why FEMA failed.” Salon.com. September 7, 2005. http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/2005/09/07/fema/index.html (accessed March 10, 2010). 26 27 Fields, Gary, and David Rogers. August 31, 2005. "Already under scrutiny, FEMA is in the spotlight." Wall Street Journal. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. http://www.postgazette.com/pg/05243/563081.stm#ixzz0jbOoFoEj (accessed March 29, 2010). 28 Congressional Record: November 19, 2002 (Senate). Volume 149, No. 15. Pp. S11455. http://frwebgate6.access.gpo.gov/cgibin/PDFgate.cgi?WAISdocID=5930433221+0+2+0&WAISaction=retrieve (accessed April 10. 2010. Entous, Adam. 17 September 2005. “Early Warnings Raised Doubt on Bush Disaster Plans.” New York Times. 29 30 31 Ibid. Hsu, Spencer S. June 26, 2006. "Can Congress Rescue FEMA?: Calls for Independence Clash with Bids to Fix the Agency Where it Is." Washington Post. P. A19. 26 32 For an overview of the role of multinational contractors in responding to Hurricane Katrina, see Klinenberg, Eric, and Thomas Frank. December 15, 2005. Looting Homeland Security. Rolling Stone.com. URL: http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/story/8952492/looting_homeland_security; 33 P. 111 in United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery. 2009. Far From Home: Deficiencies in Federal Disaster Housing Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and Recommendations for Improvement: Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 34 P. 111-112 in United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery. 2009. Far From Home: Deficiencies in Federal Disaster Housing Assistance After Hurricanes Katrina and Rita and Recommendations for Improvement: Special Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 35 FEMA looks to private sector for disaster provisions. By Zack Phillips August 24, 2007. http://www.govexec.com/story_page.cfm?articleid=37855&dcn=e_gvet 36 City of New Orleans. Office of Inspector General. April 21, 2010. Review of City of New Orleans Professional Services Contract With MWH Americas, Inc. for Infrastructure Project Management. OIG-I&E-09003(A). E. R. Quatrevaux, Inspector General, Final Report. New Orleans, LA: City of New Orleans. Pp. 5, 1. 37 City of New Orleans. Office of Inspector General. April 21, 2010. Review of City of New Orleans Professional Services Contract With MWH Americas, Inc. for Infrastructure Project Management. OIG-I&E-09003(A). E. R. Quatrevaux, Inspector General, Final Report. New Orleans, LA: City of New Orleans. 38 Ibid, Pp. 26-7. 39 Ibid, p. vi. 40 Krupa, Michelle. May 30, 2010. "Landrieu team looks to do more in-house; Outsourcing swelled after Katrina." The Times-Picayune Eggler, Bruce. July 29, 2010. “New Orleans city budget update has good news and bad news.” New Orleans Times Picayune. 41 NOLA City Council. August 13, 2010. Mayor Landrieu Launches Economic Development Public-Private Partnership. http://www.nolacitycouncil.com/content/display.asp?id=54&nid=%7B092E37FC-F3A1-4D7DB216-B9A92366E794%7D 42