Chapter 12 of Cooter and Ulen gives a number of... In 2005, the U.S. had over 2,000,000 prisoners in jails... Econ 522 – Lecture 23 (April 28 2009)

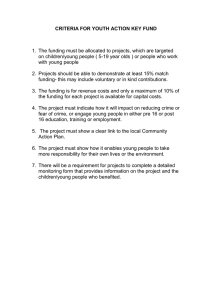

advertisement

Econ 522 – Lecture 23 (April 28 2009) Chapter 12 of Cooter and Ulen gives a number of empirical facts about crime in the U.S. In 2005, the U.S. had over 2,000,000 prisoners in jails and prisons, up from half a million in 1980; nearly another 5 million are on probation or parole 93% are male Among those in federal prisons, 60% are in for drug-related offenses The incarceration rate in the U.S. – around 0.7% – is more than 7 times that in Western Europe. Some recent history Crime rates in the U.S. (relative to population) decreased steadily from the mid1930s till the early 1960s From the early 1960s to the late 1970s, the rate of all crimes increased sharply. From the early 1980s to the early 1990s, o the rate of nonviolent crimes committed by adults dropped sharply o the rate of violent crimes by adults dropped slightly o but the rate of violent crimes by young people went up From the mid 1990s till now, both violent and nonviolent crimes have been dropping, sharply in the 1990s and more slowly since 2000. o Nonviolent crime rates have been going up overseas, so that nonviolent crime rates in the U.S. are similar or even below some European countries. o Violent crime rates are still significantly higher in the U.S., but well below their peak – from 1991 to 2004, murder rate in the U.S. fell by one-third. Criminals in the U.S. are disproportionally young males, with crime rates generally following trends in the share of the population between ages 14 and 25 Both violent criminals and their victims are disproportionally African-American. A relatively small number of people commit a large fraction of violent crimes. The book gives a few consistent characteristics of that group, they’re things you’d expect o they come from dysfunctional families o have relatives who are criminals o do poorly in school o are alcohol- and drug-abusers o live in poor and chaotic neighborhoods o and being misbehavior at a young age. -1- Cooter and Ulen try to estimate the social cost of crime The easy part to calculate is money spent on crime prevention and punishment, which is over $100 billion a year. o One third is on police o One third is on prisons o One-third is on courts, prosecutors, public defenders, probation officers, and so on. They estimate nearly another $100 billion of private money is spent on crime prevention, such as alarms and security systems, private guards, and so on. They don’t really give numbers for the direct cost of crimes – stolen property, injuries, and so on They estimate the total social cost of crime to be $500 billion, or 4% of GDP Cooter and Ulen discuss several empirical attempts to measure the extent to which punishment deters crime. As we mentioned Thursday, it’s often difficult to separate two separate effects: o deterrence – when punishment gets more severe, crime rates may go down because people are more afraid of being caught o incapacitation – when punishment gets more severe, say, through longer prison terms, so crime rates may go down just because more criminals are already in jail The early literature didn’t deal so directly with this problem, but did find that higher conviction rates and harsher punishments were associated with lower crime rates. Two studies, rather than looking at high-level crime rates, studied individual people who were likely to commit crimes: convicted criminals being released from prison o Within this population, there was still a deterrence effect: o Those with a high chance of being convicted again were arrested less in the months following release. One paper (by Dan Kessler and Steve Levitt) used a “natural experiment” to separate the deterrent effect from the incapacitation effect o In 1982, voters in California passed a ballot initiative which added 5 years to sentences for certain serious crimes for each prior conviction by the criminal o Any immediate change in crime rates should be due to deterrence, since the number of criminals in prison would only respond gradually o They found an almost immediate 4% drop in the crimes that were eligible for these “sentence enhancements” o So there did seem to be a clear deterrent effect -2- The evidence on how crime rates respond to general economic conditions is more mixed The studies tend to use national economic conditions, but you’d expect crime rates to respond more to local conditions in high-crime areas The paper on the syllabus by Isaac Ehrlich assumes that potential criminals compare the gains from illegal activity to the wages they could earn in legal jobs There is an interesting paper by Wilson and Abrahamse that explicitly does this calculation They looked at a number of “career criminals”. Two-thirds of them had relatively stable jobs when they were out of prison, and therefore at least had a reasonable estimate of their “legitimate” wages o averaged a little under $6 an hour (this was in early 1990s) Wilson and Abrahamse came up with estimates of the income from criminal activity, and compared it with the income from legitimate work They separated the criminals into two groups: “high-rate” offenders and “midrate” offenders. They found that among mid-rate offenders, crime mostly didn’t pay o working paid higher than criminal activity for most types of crime (although not for auto theft) Among the high-rate offenders, however, crime mostly did pay o criminal activity paid higher than legitimate wages for most types of crimes However, when the cost of punishment (imprisonment) were added, this finding reversed itself o adjusted for expected punishment, criminal activity paid worse than legitimate work. Wilson and Abrahamse considered, but rejected, the notion that crimes were committed because of a lack of opportunity for legal work, or because of problems with alcohol and drugs o Two-thirds of the offenders did have alcohol or drug problems, but the authors concluded that this didn’t preclude them holding down legal jobs They instead concluded that career criminals are “temperamentally disposed to overvalue the benefits of crime and to undervalue its costs” because they are “inordinately impulsive or present-oriented.” -3- We saw before that the crime rate in the U.S. dropped significantly in the 1990s A number of different explanations have been given: deterrence and incapacitation the decline of crack cocaine, which had driven much of the crime in the 1980s the economic boom of the 1990s more precaution taken by victims a change in policing strategies A paper by Donohue and Levitt (the most controversial part of Freakonomics) gave a different explanation: abortion The U.S. supreme court legalized abortion in early 1973 The number of legal abortions was on the scale of 1,000,000 a year (rising to 1.6 million by 1980), which is quite significant relative to a birth rate around 3,000,000 per year We said before that violent crimes are largely committed by males of certain ages; Donohue and Levitt argue that legalized abortion led to a smaller “cohort” of people in the high-crime age group starting in the early 1990s. (A quick aside: o birth rates, both total and relative to population, were indeed lower from 1973 to 1978 than they had been in previous years o However, they had been dropping steadily well before 1973. o Birth rates, both total and relative to population, were already substantially lower in the late 1960s and early 1970s than they had been in the 50s and early 60s o The birth rate in 1972 was the lowest it had been since 1950, when the population was substantially smaller. o So even if the demographics of adolescent youth were a large part of the drop in crime, that’s not necessarily a direct result of legalized abortion.) Donohue and Levitt do offer some interesting evidence in support of their hypothesis o For one thing, five states legalized abortion three years before Roe v. Wade; the drop in crime rates began earlier in those five states than in the rest of the country o The states with higher abortion rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s did seem to have more dramatic drops in crime from 1985 to 1997, but no different crime patterns before that point o And most of the drop in crime rate was due to a drop in crime committed by that age cohort – that is, the crime rates among “older” people in the 1990s did not fall -4- Donohue and Levitt argue that legalized abortion explains 50% of the drop in crime in the 1990s o of this 50%, half is due to its effect on the size of the cohort (just a reduction in the population of the high-crime age group) o and the other half due to its composition: that those children not born were more likely to have been born to teenage mothers, single mothers, and the poor, and were therefore disproportionately likely to become criminals Obviously a controversial finding, and not totally conclusive, but interesting We’ve already said that imprisonment has multiple effects: acts as a deterrent punishes the guilty gives an opportunity for rehabilitation incapacitates offenders Cooter and Ulen point out that incapacitation is only effective under certain situations First, incapacitation only matters if an arrested criminal won’t be immediately replaced by someone else o If you arrest the head of a drug gang, his top lieutenant might take over, and crime might go on apace o Cooter and Ulen put it this way: incapacitation is effective at reducing crime when the supply of criminals is inelastic Second, incapacitation only matters if it changes the number of crimes a person will commit, rather than just delaying them until he gets out of prison o If punishment for a third offense is very severe, most criminals might choose to only commit crimes until they’ve been caught twice o A longer sentence for the first offense may delay the second round of crimes, but not eliminate it o On the other hand, crimes that are caused by impulsive youth, and whose motivation fades with age, would be lowered by incapacitation. -5- Recent estimates are that the direct costs of holding someone in a maximumsecurity prison are $40,000 per year Some states still have prisoners do useful work o Attica State Prison in New York had a metal shop o There’s a firm in Minnesota that employs inmates as computer programmers o Medium-security prisons in Illinois make marching band uniforms. o However, there are legal limitations on this. Between 1980 and 1990, most state and federal courts moved from giving the judge wide discretion in sentencing toward mandatory sentencing In many cases, a combination of the seriousness of the crime and the offender’s past history pin down the exact punishment. Much of the increase in the prison population is traced to mandatory sentencing in drug cases. In recent years, due partly to overcrowded prisons and rising costs, there’s been some blowback. o Michigan and Louisiana recently moved from mandatory sentencing back to discretionary sentencing o Mississippi, which abolished discretionary parole in 1995, brought it back for nonviolent first-time offenders o Eighteen other states have passed some sort of sentencing reforms. -6- death penalty In 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court found that the death penalty, as it was being applied, was unconstitutional Court found that it was being applied in a way that was “capricious and discriminatory.” Following that, several states changed the way the death penalty was administered comply with the decision In 1976 the Supreme Court upheld some of the new laws. Since then, executions have averaged 41 per year, with Texas and Oklahoma combined accounting for half of them There are around 3000 prisoners on death row, and the number has been falling Since 1976, there have also been 304 inmates on death row who were found to be innocent, and many more who were pardoned or commuted by governors o In 2003, the outgoing governor of Illinois converted the sentences of all 167 Illinois prisoners on death row to life in prison. There have been numerous studies on whether the death penalty actually deters crime, and the results have varied widely o Some have found no deterrent effect o Others have found a strong one o All the results appear to be very sensitive to the exact formulation of the empirical model o (The results literally range from no effect at all on one end, to one study finding that each incremental execution prevents 150 murders, with many studies finding a much lower, but positive, level of deterrence.) One problem complicating things is that, in situations where the death penalty will almost certainly be applied, judges and juries are sometimes less willing to convict someone. There’s a recent paper by Steven Durlauf (here at Wisconsin) and three other authors o They point out that existing results on deterrence are very sensitive to the exact details of the empirical model used o Given that, they argue not that the results are useless, but that model uncertainty – that is, uncertainty over which model is correct – should be explicitly incorporated into the model o They propose a way of doing this, and find a modest, though not particularly strong, deterrent effect. o Durlauf’s explanation of the main results: If you believe the death penalty deters crime, the data won’t convince you it doesn’t; if you believe it doesn’t, the data won’t convince you it will. -7- The direct costs of capital punishment are currently quite high, due to a number of legal protections: o capital cases are longer o more jurors are rejected, so more jurors have to be made available initially o the trial is often divided into two phases, one for guilt and one for sentencing o and defendants are also entitled to automatic appeals In addition, holding someone on death row is more expensive than keeping them with the rest of the prison population In the U.S., it’s currently more expensive to execute someone than to hold them in prison for life drugs Cooter and Ulen discuss a bit the efforts to control illegal drug use They point out that increasing the expected punishment for selling drugs will increase its price What happens then depends on the elasticity of demand. o Casual (occasional) drug users tend to have fairly elastic demand o When the price of drugs (or the risk or difficulty in obtaining them) goes up, their demand goes down significantly o So punishing drug sales has the desired effect. o Addicts, on the other hand, tend to have very inelastic demand o Since they’re physically dependent on the drug, they still want to consume nearly the same amount o So price goes up, but demand stays nearly the same o What changes is expenditures – addicts must pay more for drugs o For those who support their habits via crime, this can lead to more crime. Cooter and Ulen point out that the “ideal” policy might be to raise the price to non-addicts without raising the price to addicts o Several programs in Europe to just that o Addicts can register with the government and receive drugs cheaply o Those who do not register face higher street prices o Not sure I see that happening here so much Cooter and Ulen also point out the difficulty in eradicating supply, since wiping out production in one country leads to more production in other countries And they discuss a bit the arguments for legalization in various forms -8- guns Cooter and Ulen also spend a little time discussing gun control They point out that both violent crime and gun ownership are high in the U.S. relative to Europe, and tend to be correlated over time as well However, causation could go either way o more guns might cause more crime o or more crime might lead more people to want to own guns Empirical work has not demonstrated a clear link between handgun ownership and violent crime One interesting tidbit o The U.S., Canada, and Great Britain have similar burglary rates o In the U.S., where handgun ownership is generally legal, a much smaller fraction of these burglaries occur when the victims are at home o In the U.S., “hot” burglaries are only 10% of total burglaries o In Canada and Great Britain, around 50% o So widespread gun ownership doesn’t seem to reduce the overall number of burglaries, but it changes the composition That’s all I’ll say about criminal law. Next, I want to go back over our use of efficiency throughout this class. -9- Looking back over the semester… We started out by introducing the notion of efficiency, or Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, or wealth maximization, and argued that it’s a pretty good goal for the legal system to aim for With property law, the Coase conjecture suggested that if there are no transaction costs, efficiency is easy to achieve o Just define property rights, choose any initial allocation of rights, and allow people to bargain with each other o (When there are transaction costs, this leaves us with a choice: design the law to minimize transaction costs, or design the law to allocate rights efficiently as often as possible) With contract law, we looked for rules that would yield efficient breach, and efficient reliance, and efficient disclosure of information, among other things With tort law, we looked for rules that would create incentives for efficient precaution to prevent accidents, and efficient levels of risky activities And in the last few lectures, with both civil and criminal law, we discussed designing the legal system more generally to minimize the combined cost of implementing the system and living with its errors – which is the same as maximizing the resources left to society So with each branch of the law, the question we’ve asked is, what would an efficient system look like, and how do the actual rules in place measure up to the standard of efficiency? Now that we’ve made it through all that, it seems like a good idea to look again at efficiency, and return to two key questions: is efficiency the right goal for the law? and should we expect the common law system to naturally tend toward efficiency? - 10 - We addressed the first question early in the class, starting with Posner Posner points out that the appeal of a Pareto-improvement is that everyone would consent to it He tries to make an analogous argument for Kaldor-Hicks improvements, or changes that increase overall efficiency Obviously, you can’t do this after the fact o Once I’ve hit you with my car, I’d prefer a negligence system (or a system of no liability), and you’d prefer a strict liability system But Posner introduces the idea of ex-ante compensation o He points out: “if you buy a lottery ticket and lose the lottery, then… you have consented to the loss” o And similarly: “Suppose some entrepreneur loses money because a competitor develops a superior product. Since the return to entrepreneurial activity will include a premium to cover the risk of losses due to competition, the entrepreneur is compensated for those losses ex ante.” Suppose we all agree that a negligence rule is most efficient than a strict liability rule And suppose for simplicity that everybody in society is the same – everyone is the same age, is equally good drivers, drives the same amount, and so on If I just hit you with my car, you’d prefer a strict liability rule But if we all got together before any accidents happened and chose a system, we’d both agree to the negligence rule o If you wanted to be compensated if you ever got hit by a car, you could buy accident insurance – which, if a negligence system really is more efficient, would cost less than your expected liability would be under a different system So Posner’s idea: we were all compensated ex-ante for the choice of the more efficient system. And therefore, it’s as if we all consented to it - 11 - The argument gets harder if people are different – some people don’t drive, but still get hit by cars But Posner still tries to make it more general Suppose we introduced a law that was inefficient, but favored tenants over landlords We might think that tenants would like it and landlords would not But since rental rates are determined competitively, it would probably just result in higher rents, to compensate landlords for the change in the law So Posner’s general argument: if we could all meet up to choose a rule ahead of time, we’d all choose the efficient one So assume that we all consented to it, and go with it (He points out this is like the principle in contract law, where to deal with an unforeseen contingency, you try to impute the terms the parties would have chosen, if they had addressed that scenario in the contract.) - 12 - So that’s Posner on why the law should aim for efficiency Cooter and Ulen take on the question as well, and offer another reason why the law should aim for efficiency They acknowledge that society may have goals other than efficiency o In particular, a society may care about the distribution of wealth, not just maximizing the total amount of it But, they argue, if society wants achieve redistribution, it is better to design the law to be efficient, and use the tax system to control distribution They give several reasons for why the tax system is a better way to redistribute wealth than the legal system: o The tax system can directly target people with high or low incomes, rather than relying on rough proxies (like “consumers” and “investors”, or “doctors” and “patients”) o Effects of changes in the legal system are harder to predict than changes in tax rates o Lawyers are more expensive than accountants (or really, transaction costs are higher when redistribution is through the legal system) o A law aimed at redistribution would function like a tax on a particular activity; but the more narrow a tax is, the more distortion it causes, and therefore the more deadweight loss it creates So that gives us two views for why we should aim for a legal system that is efficient, or maximizes wealth: Posner: it’s what we’d all agree to ex-ante Cooter and Ulen: if we want to redistribute, it works better to do it through taxes This brings us to the second question: can we expect the common law to naturally tend toward being efficient? - 13 - Posner gives one reason why it would He points out that many people believe the government, and the courts, respond to politically powerful interest groups But the same idea of ex-ante consent suggests that even these groups would probably want efficient laws If landlords, as a group, were more politically connected and influential than tenants, we might expect them to influence the laws But like we said before, landlords wouldn’t get that excited about inefficient prolandlord laws, because they’d probably just lead to lower rents to compensate So well-connected groups wouldn’t resist efficient rules Cooter and Ulen go further, and offer three specific mechanisms that could lead the common law toward being efficient: First, the common law often implements social norms or existing industry practices o These norms and practices likely developed, and lasted, because they were better than the alternatives, so they are likely efficient o We saw this at the beginning of the course, with whaling o The whaling industry in different places developed norms and practices which were well-suited to each environment and therefore efficient o And common-law judges chose to respect these norms, which made the common law efficient as well Second, some judges may deliberately try to make the law more efficient o Under the common law, judges generally follow precedents o But judges do occasionally reverse precedents and “make new law” o If judges are more willing to reverse inefficient precedents and replace them with efficient ones, then this will push the common law in the direction of efficiency o We saw a dramatic example of this with the Hand Rule, where the judge explicitly incorporated efficiency into the legal standard of care for a negligence rule o We also saw this with the ruling in Boomer v Atlantic Cement This was the cement factory that created dust and noise Precedent was to issue an injunction in nuisance cases But the court felt that an injunction would be inefficient, and chose to abandon precedent and order only damages - 14 - Cooter and Ulen also consider a third way the common law could naturally evolve toward efficiency: inefficient laws might lead to more litigation than efficient ones o Inefficient laws have higher social costs than efficient ones o So they must have higher costs for at least one party o So there should be a greater incentive to challenge them or violate them, leading to more litigation o Even if courts do not consciously favor efficiency, but just randomly make new law a certain fraction of the time, more litigation around inefficient rules leads to a greater chance that inefficient rules are the ones that are overturned in favor of new rules o If the new rule is inefficient, it will still lead to a large amount of litigation o But if it’s efficient, it will lead to less litigation, and will more likely survive o So the common law would evolve, over time, in the direction of efficiency o (Cooter and Ulen do concede that while this is an appealing argument, it may be a fairly weak effect o This is because the private gain from challenging a “bad” law is different from the social gain o If I go to court and get an inefficient law overturned, there is a positive externality on the rest of society o Because I bear most of the cost of doing this, but don’t get all of the benefit, the incentives to challenge inefficient laws are not that strong, and therefore it won’t happen as much as it “should”.) - 15 - However, there’s an opposing view that litigation will not always lead to efficient laws The argument is explained in a paper by Gillian Hadfield, “Bias in the Evolution of Legal Rules” Hadfield imagines that every case is a little bit different – so the “ideal” rule might vary from case to case Legal rules can’t be too complicated/ambiguous, so the best the court can hope to do is to be right “on average” The court will form an opinion of what rules are efficient on average based on the cases it sees But the cases the court sees will not be a random sample of all possible cases That is, since there will be a bias in which cases go to trial, the court will have a biased view of what rules are efficient. How does this work? A given legal rule will have different effects on different individuals/firms Some might find it not that costly to follow the rule: Hadfield calls these compliers Others will find it too costly to comply with the rule, and will choose to be violators And finally, some might both these options too costly, and drop out of the market entirely. Being “right on average” means doing what is efficient, given the true mix of compliers and violators But the court mostly sees cases involving violators, so it is likely to choose the rule which would be efficient if everyone in the market looked like the violators If compliers and violators are different enough, this rule will not be efficient overall - 16 - For example We made the point earlier that successive application of the Hand Rule could be used to clarify the standard for negligence Suppose product liability in a certain industry is covered by a simple negligence rule, and the Hand Rule is used to determine the legal standard of care. First, suppose all the firms in the industry face the same cost-benefit tradeoff from taking precaution. TSC wx p(x) A precaution Firms initially take a low level of precaution, so there are some accidents Some lead to lawsuits, the court finds that more precaution would have been costjustified, firms respond by taking a higher level of precaution Eventually, some lawsuits fail because more precaution was not cost-justified, and we’ve stumbled upon the efficient level of precaution, which is now the legal standard for avoiding negligence - 17 - But now suppose all the firms in the industry aren’t the same Suppose that for whatever reason, some firms find it fairly cheap to take precaution, while some firms find it expensive The court can’t distinguish between these firms, so it can’t mandate different levels of care for the two types of firms (Or even if it could, maybe it shouldn’t.) A legal standard for negligence would lead (in theory) to every firm taking the same level of precaution The level that would minimize total social costs would be based on the average costs of all the firms in the industry. (DRAW IT) However, think about what would actually happen as firms applied the Hand Rule Suppose there’s initially some uncertainty about the exact legal standard o Firms who can take precaution cheaply don’t have any need to run the risk o They can set a high level of precaution, leading to very few accidents and very few lawsuits, and be fairly sure they’ll avoid liability when accidents do occur. o On the other hand, the firms who find it very costly to take precaution will take less o Even if they want to meet the legal standard of care, they have a much greater incentive to “cut it close” – to just barely meet the legal standard, rather than exceed it by a lot o Some firms may even find precaution so costly that they choose to ignore the legal standard and accept liability. - 18 - But now think about the cases the court will see: they will consist almost entirely of cases involving firms with high precaution costs The court can only use the information it has So as it applies the Hand Rule, it will constantly be assessing what precautions are cost-justified for these higher-cost firms So by applying the Hand Rule, courts will settle on a legal standard based on what is cost-justified for high-cost firms This rule would be efficient if all the firms in the market were high-cost But applying this rule to all the firms in the market – both the low- and the highcost firms – is inefficient (In this case, it sets the level of precaution below the socially optimal level, leading to too many accidents.) Numerical example of Hadfield (skip) Four possible levels of precaution: none, low, medium, high Accidents cost $1,000 Chance of an accident: 20%, 10%, 5%, 1% Two types of firms: high-cost and low-cost High-cost firms: $0, $60, $120, $180 Low-cost firms: $0, $30, $60, $90 Equal number of high- and low-cost firms Efficient rule: high-cost firms should take low precaution, low-cost firms should take high precaution Single rule for every firm: most efficient would be for everyone to take medium level But if the initial rule is unclear, low-cost firms will take more precaution than high-cost firms, so it will mostly be … - 19 - Hadfield’s claim is that this will happen not just in setting negligence standards, but in any situation where the court adjusts the legal rule based on what appears efficient from the cases it sees Whatever the existing rule, it will lead to some “compliers” and some “violators” The court will mostly see cases involving violators, so it will gravitate toward rules that would be efficient if everyone was violators As long as compliers and violators are different enough, these rules will not be efficient. Hadfield doesn’t use a formal model, but argues the point fairly well She argues that o as long as there is enough heterogeneity among potential cases o that is, as long as different cases vary enough to merit different optimal rules o and as long as the court only learns about cases that go to trial o this bias will lead to inefficient rules She also discusses the assumption that courts only learn about the cases they see, and why this is So that gives us a few reasons why the common law will naturally be efficient, and one reason why it might not We’ll end there for today Thursday: I’ll recap what we’ve done this semester, try to show a couple of consistent themes, and wrap up Next week: optional lecture on Tuesday - 20 -