On Tuesday, we asked the question of what promises the... introduced contract law as the attempt to answer that question.

advertisement

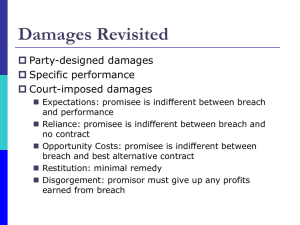

Econ 522 – Lecture 10 (February 19 2009) On Tuesday, we asked the question of what promises the law should enforce, and introduced contract law as the attempt to answer that question. We talked about one early attempt to answer the question, the bargain theory of contracts, and some of the problems with it. o Under the bargain theory, promises are legally enforceable if they were given as part of a bargain; there are three elements that must be present, offer, acceptance, and consideration We showed an example of an agency game, where my inability to commit to a future action (in that case, returning your investment) led to a breakdown in cooperation… …we said that the first purpose of contract law is to enable cooperation, by turning games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solutions… …and we argued that efficiency generally requires a promise to be enforceable if both the promisor and the promisee wanted it to be enforceable when it was made We saw an example of how asymmetric information can inhibit trade… (the example of you being unable to buy my used car, because I “know too much” about its condition and have no incentive to tell you what’s wrong with it) …and claimed that the second purpose of contract law is to encourage the efficient disclosure of information We discussed the fact that efficiency sometimes requires breaching a contract… …and said that the third purpose of contract law is to secure optimal commitment to performing… …and argued that setting the promisor’s liability equal to the promisee’s benefit – expectation damages – accomplishes this goal We introduced the idea of reliance, that is, investments made by the promisee to increase their benefit from the promise… …and said that the fourth purpose of contract law is to secure the optimal level of reliance… …and then we ran out of time. -1- Today, I want to give an example of efficient breach give an example of reliance then move on to default rules and mandatory rules We begin with an example of efficient breach Suppose that I build airplanes, and you contract to buy one from me You value the airplane at $500,000 We agree on a price of $350,000 It will simplify the example if we assume you paid me up front; so let’s assume this contract was money-for-a-promise: you already paid up front and I promised to deliver a plane o (This doesn’t really matter much, it just makes all the numbers positive.) The rule for efficient breach is: If [ Promisor’s Cost ] > [ Promisee’s Benefit ] Efficient to breach If [ Promisor’s Cost ] < [ Promisee’s Benefit ] Efficient to perform The promisee’s benefit is known to be $500,000 So it’s efficient to perform whenever the cost of building the airplane is below $500,000, and efficient to breach whenever the cost is above $500,000. Since the promisor only looks at his own private cost and benefit when deciding whether to breach or perform, If [ Promisor’s Cost ] > [ Liability ] Promisor will breach If [ Promisor’s Cost ] < [ Liability ] Promisor will perform In the case of expectation damages, the promisor’s liability would be the amount of benefit the promisee would have received, which is $500,000 This leads to the promisor performing whenever the cost of building the airplane is less than $500,000, which is exactly what efficiency would require -2- This is what we saw Tuesday – expectation damages, which set liability equal to the promisee’s benefit, lead to breach exactly when it’s efficient. It turns out that any other level of damages would lead to inefficiency Suppose liability were just $350,000 – I can just return your money and get out of building you the plane Then if the cost of building you the plane goes up to $400,000, I would choose to breach, even though performance is efficient – the plane is worth more than it costs to build On the other hand, suppose the penalty for breach of contract was very large – if I breach the contract, I have to pay you $1,000,000, almost triple your money back Then if the cost of building the plane goes up to $700,000, I would perform, even though performance is inefficient – the plane costs more than it’s worth So what, you might ask? Remember Coase? If transaction costs are low, we can just negotiate again, right? Go back to the first example – if I breach, I just owe you your money back We agreed on a price of $350,000 The cost of building the plane goes up to $400,000 I decide to breach We can just renegotiate and agree on a new price of $450,000 But if I can get out of a promise just by returning your money, it might be tempting for me to do this too often, just to try to raise the price Suppose the cost doesn’t change at all But I know you agreed to pay $350,000, so you must value the plane more highly than that So I go to you with a made-up story about one of my workers threatening to quit unless he gets a raise, I tell you my costs went up, and you can only have the plane if you’re willing to pay me $400,000 If it’s too easy to get out of a contract, agreements become meaningless And if transaction costs are high – say, you’re mad because I breached the first contract, and don’t want to deal with me anymore – then you don’t get your plane, even though it would be efficient for me to build it. -3- Now go back to the second example – if I breach, I owe you $1,000,000 Now my costs actually go up, and it would cost me $700,000 to build the plane I go to you and say, “look, I know I promised you a plane, but it would cost me $700,000 to build, can we just agree to undo the deal?” And you say, “Sure, just give me the $700,000.” And I say, “Why? You were only going to get $500,000 of benefit out of the plane.” And you say, “Yeah, so what? If you don’t give me a plane, you owe me a lot more than that. So give me $700,000, or else.” What’s the problem with that? In a static world, nothing Me being forced to pay you $700,000 to get out of my promise is annoying to me, but it’s not inefficient But now go back to when we were originally agreeing to the contract If I know there’s a small chance my costs will go way up, and if contracts are strong enough that you could do this to me, then maybe I don’t want to take the risk of making the promise in the first place So now even though it might be efficient for me to agree to build you a plane, I’d be afraid to make that promise. On the other hand, if the cost to me of breaching the contract – my liability – is exactly equal to your benefit, there is no problem I’ll still build the plane exactly when it’s efficient for me to build the plane – whether or not transaction costs are low enough that we could renegotiate We’ll see later that expectation damages don’t perfectly solve the problem of efficient signing – being willing to sign the right contract in the first place – but at least it doesn’t make this problem too severe. -4- So that’s efficient breach. Next, reliance You’ll recall that reliance is any investment the promisee makes that increases the value of performance So you contract to buy my painting, and go buy a frame for it Or you contract to buy an airplane from me, and you start building a hangar Since reliance increases the value of the promise to you, it increases my liability for breach under the concept of expectation damages as we’ve defined them (That is, if I break my promise, I’m responsible for making you as well off as you would have been if I had kept my word; so if you’ve built a hangar, now I have to reimburse you for the value of the plane with a hangar, rather than the value of a plane without a hangar.) So reliance increases my losses under breach But you don’t take that into account when deciding how much to invest in reliance So there is no guarantee that the level of reliance will be efficient. We’ll use the same example – you contract to buy a plane from me This time, it will be simpler if the bargain was promise-for-a-promise – you agree to pay on delivery And assume the penalty for breach of contract is expectation damages You value the plane at $500,000, and agree to pay $350,000 for it Now you have the option of building yourself a hangar Suppose that building a hangar costs $75,000, and increases the value of owning a plane from $500,000 to $600,000. Suppose that it’s most likely that building the plane will cost me $250,000; but that there’s some probability p that it will instead cost $700,000 Clearly, if it costs $700,000, I won’t build it; I’ll just breach the contract and pay you whatever damages I owe -5- Let’s look at what happens under each outcome First, suppose the cost of the plane is $250,000, so I build it. Our payoffs (in thousands): If you relied (built the hangar): you get 600 – 75 – 350 = 175 I get 350 – 250 = 100 If you didn’t rely (build) you get 500 – 350 = 150 I get the same 350 – 250 = 100 Now look at the case where the cost of sheet metal went through the roof and I choose to breach. I owe expectation damages as we’ve defined them – that is, enough to make you as well off as if I’d performed. If you relied (built the hangar): Your surplus would have been 600 – 350 = 250 from the plane, so I owe you 250 in damages And you paid 75 to build the hangar So you end up with payoff of 175 I get –250 (since I have to pay you 250 in damages) If you didn’t rely (build) Your surplus would have been 500 – 350 = 150, so I owe you 150 in damages, which is your payoff I get –150 after paying you damages So whether or not I perform, you get 175 if you relied, 150 if you didn’t. So clearly, reliance makes you better off. But then the question is, is reliance efficient? That depends on how likely I am to breach. Let p be the probability that costs go up, that is, the probability of breach If you rely, our combined expected payoffs are (1–p) (175 + 100) + p (175 – 250) = 275 (1–p) – 75 p = 275 – 350 p If you didn’t rely, our combined expected payoffs are (1-p) (150 + 100) + p (150 – 150) = 250 – 250 p So the total social gain from you building the hangar is (275 – 350 p) – (250 – 250 p) = 25 – 100 p -6- So it turns out that when p < ¼, reliance is efficient – it increases our combined payoffs. When p > ¼, reliance is inefficient – it decreases our combined payoffs. This is indicative of a more general idea: when the probability of breach is low, more reliance tends to be efficient; when the probability of breach is high, less reliance tends to be efficient. But if my damages cover your benefit whether or not it’s efficient, then you don’t care about the risk of breach – you end up just as well off whether or not I breach So you’ll clearly choose the higher level of reliance, whether it’s efficient or not This will sometimes lead to overreliance – more reliance than is efficient. So how do we fix this? Cooter and Ulen adjust their definition of expectation damages in the following way: Perfect expectation damages restore the promisee to the level of well-being he would have had, had the promise been kept, and had he relied the optimal amount (This is why they attach the word “perfect” to expectation damages) Thus, the promisee is rewarded for efficient reliance o this increases his payoff from performance of the promise, and also increases his payoff from breach, since it increases the amount of damages he receives But the promisee is not rewarded for excessive reliance – overreliance o damages are limited to the benefit he would have received given the optimal level of reliance. It’s a nice idea, but it seems like it would be very hard in general for a court to determine after the fact what the optimal level of reliance was (It might also be hard for the promisee to know this, since he may not know the probability of breach.) What is actually done in practice? The usual rule is that liability is limited to the level of reliance that is foreseeable. Reliance is foreseeable if the promisor could reasonably expect the promisee to rely that much under the circumstances Reliance is unforeseeable if it would not be reasonably expected American and British law tend to define overreliance as unforeseeable, and therefore noncompensable. -7- An example of unforeseeable reliance telegraph company fails to transmit a stockbroker’s message, resulting in millions of dollars in losses the telegraph company could not reasonably expect the stockbroker to rely that heavily on one message so the telegraph company would not be liable for the full extent of the losses Another example: the rich uncle’s nephew, when he was promised a trip around the world, goes out and buys “a white silk suit for the tropics and matching diamond belt buckle”. After the uncle refuses to pay for the trip, the nephew sells the suit and belt buckle at a loss, and sues his uncle for the difference The court might find the silk suit foreseeable reliance, but the diamond belt buckle unforeseeable, and only award him the loss on the suit. (The book points out that “in American law, gift promises are usually enforceable to the extent of reasonable reliance.”) -8- Reliance is part of the issue in the famous case of Hadley v Baxendale, a precedentsetting English case decided in the 1850s I give a link to the actual court decision on the syllabus Here is Cooter and Ulen’s summary of the case: Hadley owned a gristmill; the main shaft of the mill broke; and Hadley hired a shipping firm where Baxendale worked to transport the shaft for repair. The damaged shaft was the only one in Hadley’s mill, which remained closed awaiting return of the repaired shaft. The shaft was supposed to be delivered in one day Baxendale decided to ship it by boat instead of by train, and as a result, it arrived a week late Hadley sued for the profits he lost during that extra week in which the mill was shut down Quoting again: The shipper assumed that Hadley, like most millers, kept a spare shaft. The shipper contended that Hadley did not inform him of the special urgency in getting the shaft repaired. The shipper prevailed in court on the damages issue, and the case subsequently stands for the principle that recovery for breach of contract is limited to foreseeable damages. The ruling was that the lost profits were not foreseeable o the court specifically listed several circumstances in which a broken crankshaft would not force a mill to shut down Baxendale was only held liable for damages he could reasonably have foreseen However, this isn’t only a question of reliance Part of the issue is that Hadley knew about the urgency of getting the crankshaft fixed quickly, but did not tell Baxendale Recall on Tuesday, we said that the second purpose of contract law is to encourage the efficient disclosure of information We’ll come back to this question of information shortly. -9- default rules In a world without any transaction costs, the two sides to a contract could spell out exactly what should occur in every possible contingency o what happens if the cost of sheet metal rises o what happens if my uncle wants my painting o what happens if a shipment is delayed, and so on This would make contract law much simpler – courts could simply enforce the letter of the contract, since nothing was left unclear However, in reality, some circumstances are impossible to foresee And even if they weren’t, the cost and complexity of writing a contract to deal with every possibility would make perfect contracts unworkable Risks or circumstances that aren’t specifically addressed in a contract are called gaps; default rules are rules that the court applies to fill in these gaps. Gaps can be inadvertent or deliberate Our contract to sell you my painting might not have addressed my uncle wanting the painting because I didn’t know he was coming to visit, or because I never would have imagined he would be so excited about it On the other hand, we could have imagined that it was at least possible for the price of raw materials for building an airplane to go up significantly But we might have felt it was such a remote risk that it was not worth the time and effort to build it into the contract. The decision to leave a gap or to fill it (specifically address a particular contingency) is the difference between allocating a loss after it has occurred (ex post) and allocating a risk before it becomes a loss (ex ante) At the time I agree to build you an airplane, there is some risk that the cost of raw materials will go up We can choose to worry now about who should bear that risk Or we can leave it out of the contract, and if that risk becomes a loss (that is, if the costs do go up), then we can worry about who should bear the loss In the first case, allocating the risk, the cost of adding it to the contract is definitely incurred But in the second case, allocating a loss that has occurred, the cost of allocating the loss is only incurred when the loss occurs Thus, it is often rational to leave gaps when the risk is very remote - 10 - But this means that courts must decide what “default rules” should apply to circumstances that are not addressed in a contract That is, what rules should fill the gaps that are left in imperfect contracts The next obvious question is: what should these default rules be? We will look at two different views of this Cooter and Ulen answer this question by going back to the Normative Coase view: the law should be structured to minimize transaction costs Since filling a gap in a contract requires some cost, the default rule should be the rule that most parties would want if they chose to negotiate over the issue This way, most contracts will not have to address this particular rule – they can use the default rule – and therefore avoid additional transaction costs And the rule that most parties would want is whatever rule is efficient. They give an example A construction company has contracted to build a house for a family, and there is some risk of a worker strike at the company which would delay completion Suppose that the company can bear the risk of a strike at a cost of $60, and that the family can bear the risk at a cost of $20 (It might be cheaper for the family to bear the risk because they could stay with friends for a while if the house were delayed; if the company held the risk, it might have to pay for a hotel for the family.) (Also note that these numbers are low not because a strike would have low costs, but because a strike might be fairly unlikely, so the expected cost is fairly low.) If the risk were not addressed by the contract, the default rule would apply. If the default rule were for the construction company to bear the risk, this would be inefficient in this case The parties could create an additional $40 of surplus by overruling the default rule (addressing the risk) So as long as the transaction cost of allocating the risk were not too large, they would choose to do so, but incur this transaction cost. On the other hand, if the default rule were for the family to bear the risk, they would not need to address the risk in the contract, and would not incur the transaction cost. - 11 - This brings Cooter and Ulen to their fifth pronouncement: The fifth purpose of contract law is to minimize transaction costs of negotiating contracts by supplying efficient default rules. (leave space) They also offer a simple rule for doing this: Impute the terms to the contract that the parties would have agreed to if they had bargained over the relevant risk. That is, figure out what terms the parties would have chosen if they had chosen to address a risk, and let those be the default rule. Of course, you don’t want a lot of ambiguity in the law So you don’t want the default rule to vary constantly with the particular circumstances of a given case So what’s more practical to do is to set the default rule to the terms that most parties would have agreed to This is called a majoritarian default rule In circumstances where this is not the efficient rule, the parties are still free to contract around it, that is, to put terms in the contract that override the default rule If the parties had chosen to address a particular risk, it’s safe to assume that they would have allocated it efficiently That is, as long as the parties were choosing to consider a risk, they would allocate it in the way that led to the highest total surplus, and then compensate the party who bears the risk for bearing it Thus, this is what the court would need to do to figure out the efficient default rule: it should figure out the efficient allocation of risks, and then adjust prices in a reasonable way The book gives an example of this Again, suppose a family is having a house built The family and the construction company are negotiating a contract The construction company knows that with probability ½ , the price of copper pipe will go up in such a way as to increase the cost of construction by $2,000 So in expectation, the cost of construction will be $1,000 higher due to this risk The company can hedge against this risk (by buying copper pipe in advance and then paying to store it somewhere) at a cost of $400 Assume that the family has no reason to know anything about the cost of copper pipes, and therefore does not anticipate the risk or have any way to mitigate it. - 12 - The company chooses not to hedge this risk The price of copper pipes does go up The company builds the house and bills the family $2,000 more than they had expected The family refuses to pay, and the case goes to court The original contract does not say anything about the risk of rising copper prices. So how would the court address this? First, the court must decide to whom the contract would have allocated this risk, if it had addressed it. Then it must adjust prices to reflect this. In this case, the cost of bearing the risk would be $1,000 to the family (since they have no way to mitigate it), but $400 to the company (since hedging the risk is cheaper than bearing it) So the company is the efficient bearer of the risk That is, an efficient contract would have allocated this risk to the construction company Next, the court must consider whether the price should be adjusted In this case, the court might rule that the risk of a spike in copper prices was foreseeable The construction company was the efficient bearer of risk, and foresaw, or should have foreseen, that this risk was present So the court could assume that the price the parties negotiated already included compensation for bearing this risk On the other hand, there are some risks that are unforeseeable Suppose that the leader of the copper miners’ union in Peru died, and there was a battle to succeed him, and that his replacement called a strike to flex his muscles, and that this strike was what led to the increase in copper prices Here, it’s reasonable that neither party would have foreseen the risk. In this case, the construction company might still be the efficient bearer of this risk – since they might be able to make changes to the construction plan to use less copper and more of other materials But since the risk was unforeseen, it was not included in the negotiated price So the court might adjust the price paid to the construction company, to compensate them for the risk; but then still hold the construction company responsible for the extra $2,000 in costs - 13 - Thus, the ruling might be that the family should pay some smaller amount – say, $700 – which is what the company would have needed to receive as compensation for bearing this risk – but that the company was then responsible for the rest of the $2,000. (The book then continues this story to give another example of overreliance and breach – check it out if you’re still confused about these points.) So the rule in Cooter and Ulen is fairly straightforward: Courts should set default rules that are efficient in the majority cases, so that… o most parties can leave that risk unaddressed and save on transaction costs o while parties can contract around this rule in circumstances where it is not efficient. Ian Ayres and Robert Gertner offer a very different take on default rules, in the article on the syllabus, “Filling Gaps in Incomplete Contracts: An Economic Theory of Default Rules.” They argue that in some instances, it is better to make the default rule something the parties would not have wanted Either to give the parties an incentive to specifically address an issue rather than leaving a gap Or to give one of the parties an incentive to disclose information They refer to this type of intentionally-inefficient default rule as a penalty default Ayres and Gertner argue that in some cases, gaps are left not because the of the transaction costs of filling them, but for strategic reasons One party might know that the default rule is inefficient; but negotiating around the default rule would require him to give up some valuable information, so he might be tempted not to - 14 - Consider again the case of Hadley v Baxendale, the miller with the broken crankshaft While the crankshaft is en route, Hadley’s mill is not operating, so he’s losing money Baxendale, the shipper, is the only one who can influence when the crankshaft is delivered; so he is likely the efficient bearer of this risk (It was his choice to ship the crankshaft by boat, rather than by rail, that led to the delay.) If the default rule were for Baxendale to be responsible for any lost profits, however, Hadley has no incentive to tell him how urgent the shipment is In fact, he is likely to not want to mention it; if he made it clear how important the crankshaft was, Baxendale might try to charge him a higher price for delivery! So a default rule holding Baxendale responsible for lost profits due to delay would lead Hadley not to disclose the urgency of his shipment And this would be inefficient, since it could lead to Baxendale making a bad decision about what method of shipment to use (this is what happened) On the other hand, a default rule that Baxendale is not responsible for lost profits seems to be inefficient o we just argued that Baxendale is the efficient bearer of this risk This gives Hadley an incentive to try to negotiate different terms in the actual contract Over the course of the negotiations, the urgency would become apparent Baxendale would agree to take on the risk But he would also know the costs of delay, and could plan around them better. So Ayres and Gertner argue that the ruling in Hadley was a good one Not because the default rule was efficient But because it was inefficient in a way that created good incentives In this case, the incentive for the better-informed party to disclose information (In this sense, the default rule is a “penalty default:” it penalizes the betterinformed party, giving an incentive to contract around the default.) - 15 - Ayres and Gertner offer other examples where penalty defaults are used in the same way Consider a real estate broker who is handling the sale of a house by a private seller to a private buyer When a buyer’s offer is accepted, he puts down a deposit, called “earnest money,” to show that he is serious If he then backs out of the deal, he doesn’t get this earnest money back The question remains, though, how should the earnest money be divided between the seller and the broker? Both the broker and the seller are inconvenienced by the breach; it’s not really clear who is the efficient bearer of this risk However, what is clear is that the broker probably knows more about real estate law than the seller o The broker is a professional, who does this type of transaction for a living o The seller might be selling a house for the first time. If the default rule allowed the broker to keep the earnest money, the broker has no reason to bring this up when negotiating a contract with the seller But the seller might not know to bring this up; the seller might have no idea about earnest money, and not realize that this was another point that could be negotiated with the broker. On the other hand, if the default rule gave the earnest money to the seller, the broker would have a clear incentive to raise this with the seller And so they could negotiate whatever was the efficient allocation of the earnest money. Thus, whether or not it’s efficient, a default rule favoring the less-informed party once again gives an incentive to disclose information, which may be desireable. - 16 - Ayres and Gertner give another nice example of penalty defaults used for a different purpose When a contract does not specify a price for a good, courts will tend to impute whatever the market price was at the time of the transaction That is, they will enforce the contract, and just impose the market price However, when a contract does not specify a quantity, courts will refuse to enforce the contract This means the default rule for price is the market price, but the default rule for quantity is 0 A quantity of 0 cannot possibly be what the parties would have wanted Nobody would go through the hassle of signing a contract in order to transact no goods So what is the reason for this default rule? Ayres and Gertner argue it is a penalty default, to force the parties to decide on a quantity Why should the parties be forced to decide on a quantity and not a price? Because it’s easier (cheaper) for the court to fill in the price than the quantity The rule for figuring out the price the parties would have agreed to is easy – the court can usually ascertain the market price of a given good on a given date However, if the court had to impute the quantity the parties would have wanted, this is much more difficult The court would have to figure out the marginal value of an incremental unit of the good to each side to figure out the efficient amount to transact Thus, shifting the burden of calculating the right quantity from the parties in the contract to the courts is inefficient So the default rule forces the parties to decide on the quantity themselves. Ayres and Gertner do not argue penalty defaults should always be used, only that they are appropriate in certain circumstances They basically argue that we need to look at why parties to a contract leave a particular type of gap When gaps are left due to transaction costs of filling them, efficient defaults make sense However, when gaps are left strategically – by a well-informed party who chooses not to contract around an inefficient default in order to get “a bigger share of a smaller pie” – penalty defaults may be more efficient. - 17 - In the conclusion to their paper, Ayres and Gertner cite a similar point from a dissent by Supreme Court Justice Scalia The legislature had passed a RICO (racketeering/corruption) statute and had not specified a statute of limitations The Court was therefore being asked to decide on the statute of limitations The majority set the statute of limitations at 4 years, figuring that’s what the legislature most likely would have chosen had they remembered to specify it Scalia proposed no statute of limitations He was “unmoved by the fear that this… might prove repugnant to the genius of our law” Instead, he pointed out, “indeed, it might even prompt Congress to enact a limitations period that it believes appropriate, a judgment far more within its competence than ours.” So his view: rather than do what Congress would have wanted, do something they would not have wanted, to force them to do it themselves next time Exactly the same idea as a penalty default for a contract It’s a pretty cool article – take a look if you’re interested. - 18 - Default rules are rules which hold when a contract leaves gaps, but which parties to a contract are free to contract around That is, by specifying what should happen in a particular situation, the parties can override the default rule If the default rule did not hold shippers liable for unforeseen losses, Hadley and Baxendale could still choose negotiate a contract under which the shipper was liable for all losses However, there are some rules that cannot be contracted around Ayres and Gertner refer to these as immutable rules Cooter and Ulen refer to them as mandatory rules, or as regulations Their Fifth Purpose of Contract Law, which we mentioned earlier, is actually, The fifth purpose of contract law is to minimize transaction costs of negotiating contracts by supplying efficient default rules AND REGULATIONS. What are the circumstances where regulations, or mandatory rules, or immutable rules, make sense? That is, in what circumstances should a rule be made that individuals are not able to voluntarily contract around? Think back to Coase If individuals are rational and there are no transaction costs, private negotiations (in this case, contracting) will lead to efficiency So if individuals are rational and there are no transaction costs, any additional regulation would just get in the way On the other hand, when individuals are not rational, or when there are transaction costs or market failures, regulation/immutable rules might be efficient Next week, we will look at a bunch of these cases. - 19 -