efficiency “goodness”, and considered two arguments why the law should be... efficient:

advertisement

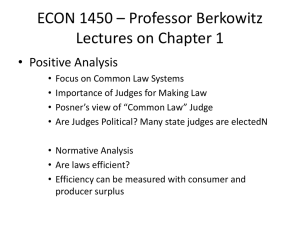

Econ 522 – Lecture 3 (Jan 27 2009) Last lecture, we defined efficiency, considered its limitations as a measure of normative “goodness”, and considered two arguments why the law should be designed to be efficient: Posner: “ex-ante consent” – if we all negotiated a legal system before we knew which part we’d play, we’d all agree to the one that was wealth-maximizing Cooter/Ulen: if we’re worried about distribution/equity, we should still design the law to be efficient, and use the tax system to redistribute wealth I realized after Thursday’s lecture that there were a couple of details of the lecture that stuck out, but that I think are very representative of how I teach First of all, I personally don’t have a lot of “absolute beliefs” in economics If you read Posner, he believes very strongly that efficiency is the right way to design the law, and that the common law will naturally evolve in the direction of efficiency (We’ll come back to the latter point at the end of the semester) Posner offers some rational arguments for these positions, but at times, he also seems to take them almost as an act of faith That’s pretty reasonable – Posner has been a law professor for 40 years, and a judge for almost 30; he knows a lot more than me about a lot of things But to me, there are very few certainties about economics If you give me something – the notion that efficiency is the “right” measure to try to get the law to conform to – I can always think of arguments in favor and arguments against And I have a tendency to make this class more confusing than it has to be, by giving you both Thursday’s lecture would have been simpler if I had said, “Efficiency means X. In this class, we want the law to be efficient. Here’s why. Let’s move on.” But that’s not how I see the world. I hope that it isn’t too confusing when I do things like this: give both the principle (what efficiency is, and how we’ll use it in this class) but also the reasons for skepticism -1- This brings me to my other point Since I don’t see economics as a bunch of certainties, how do I know the things I know? Well, the way I believe something is true in economics is to see how it works That is, to see a model, or an example, that demonstrates it So last Thursday, I made the claim that narrower taxes cause greater distortion, and therefore greater inefficiency (or deadweight loss) But I know this not because someone told me; I know it because I can give a simple model that shows it And so that was the purpose of the example I showed – to try to SHOW you that narrower taxes cause greater distortion, rather than just asking you to believe me I’ll often try to do this – introduce an example to prove a point I sometimes go through these examples a bit fast – I suspect I did this on Thursday Please feel free to ask me to slow down, or ask questions if you miss a step (Also, as some of you have probably discovered, I post my lecture notes online after each lecture, so hopefully this helps if you missed a step) Now, for today, I want to do two things: first, introduce some basic game theory second, begin talking about the first major section of this course, property law. -2- First, a brief introduction to game theory Specifically, Static Games, or Simultaneous-Move Games – that is, games where all the players decide what to do at the same time. A static game is completely described by three things: Who the players are What actions are available to each player What payoffs each player will get, given his own action and the actions of the other players The simplest games to analyze are those with two players, and a finite number of actions for each player; games like these can be summarized in a payoff matrix We’ll use a classic example, the referred to as the Prisoner’s Dilemma (story): Player 1’s Action: Shut up Rat on his friend Player 2’s Action: Shut up -1, -1 0, -10 Rat on his friend -10, 0 -5, -5 When one player’s best move does not depend on what his opponent does, this is called a dominant strategy In this case, considering only his own payoffs, player 1 is always better off ratting on his friend If his friend keep quiet, this is because 0 > -1 If his friend rats on him, this is because -5 > -10 Similarly, player 2 is better off ratting, regardless of what player 1 does So game theory predicts that both players rat, for payoffs of (-5, -5) Even though if they both kept quiet instead, they’d get (-1, -1). In many games, players won’t have a single move that’s always best; their best move will depend on what the other player (or players) is doing In those cases, the way we solve a game is to look for a Nash Equilibrium Nash Equilibrium is a plan (an action) for each player such that if everyone else sticks to the plan, I should stick to the plan as well That is, a Nash Equilibrium is a set of strategies, one for each player, such that if I believe everyone else is going to play their equilibrium strategy, I can’t do any better by playing a different strategy. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, both players ratting is an equilibrium o If I know my friend is going to rat, I still want to rat And it turns out to be the only equilibrium -3- In general, in a normal-form game, the easiest way to find Nash equilibria is to circle each player’s best-responses to each of his opponent’s potential moves: Player 1’s Action: Shut up Rat on his friend Player 2’s Action: Shut up -1, -1 0, -10 Rat on his friend -10, 0 -5, -5 Any square that has both payoffs circled is a Nash Equilibrium. Some games will have multiple equilibria. For example, the Battle of the Sexes: Player 1’s Action: Baseball Game Opera Player 2’s Action: Baseball Game 6,3 0,0 Opera 0,0 3,6 Some games will have multiple equilibria where one seems obviously better than the other: Player 1’s Action: Up Down Player 2’s Action: Left 50,50 0,0 Right 0,0 1,1 In this case, (Up, Left) Pareto-dominates (Down, Right) – both players are better off. So if the players could communicate, you’d expect them to play the “better” equilibrium But (Down, Right) is still an equilibrium – if 1 expects 2 to play Right, he should play Down; and if 2 expects 1 to play Down, he should play Right. -4- Some games – especially games where the players’ interests are opposite to each other – do not have any Nash equilibria where each player plays a single strategy. An example: consider playing a single round of Rock/Paper/Scissors, where the loser will pay the winner a dollar: Player 1: Rock Paper Scissors Player 2: Rock 0,0 1, -1 -1, 1 Paper -1, 1 0,0 1, -1 Scissors 1, -1 -1, 1 0,0 In a game like this, equilibrium is found by assuming that each player flips a coin at the last minute, and does what the coin says; his opponent knows what probability he puts on playing each of his actions, but not which one he will actually use. It turns out, the only equilibrium in this game is for each of us to play each strategy with equal probabilities This is called a mixed-strategy equilibrium, since the equilibrium involves the players playing a mixture of different strategies But in this class, we’ll be focusing on games that do have pure-strategy equilibria. -5- Next, on to Property Law We begin with the question: Why do we need property law at all? In a sense, this is simply a question of why we prefer an organized society of any sort to anarchy Suppose there are two neighboring farmers, who can do one of two things: farm their own land, or steal crops from their neighbor. Stealing is probably less efficient than planting my own crops o I have to carry the crops from your land to mine o I may drop some along the way o I have to steal at night, so you won’t see me, so I have to move slower But if I steal your crops, I don’t have to put in all the effort of planting and watering – I let you do the work and I steal at the end, just before you harvest. Suppose that planting and watering costs 5, the crops either of us could grow are worth 15, and stealing costs 3. If there is no legal system, the game has the following payoffs: Farmer 1 Farm Steal Farmer 2 Farm 10, 10 12, -5 Steal -5, 12 0,0 Just like the prisoner’s dilemma – both farmers stealing from each other is the only equilibrium, even though that outcome is Pareto-dominated by both farmers actually farming Now suppose there were lots of farmers facing this same problem And they came up with the idea to institute some property rights, and some type of government that could punish people who steal others’ crops Obviously, setting up this system would cost something – suppose it imposes costs of c on everyone who behaves well. Now the game becomes Farmer 1 Farm Steal Farmer 2 Farm 10-c, 10-c 12-P, -5-c Steal -5-c,12-P -P,-P If the punishment is big enough, and the cost to each farmer is not too big, this would establish (Farm,Farm) as an equilibrium, where before the only equilibrium was (Steal, Steal). So now we’re much better off. The main idea here is that anarchy is inefficient – I spend time and effort stealing from you, or defending my own property from thieves, instead of doing productive work. Establishing property rights, and legal recourse for when they are violated, is one way to get around this problem. -6- Overview of Property Law Cooter and Ulen define property as “a bundle of legal rights over resources that the owner is free to exercise and whose exercise is protected from interference by others.” Of course, property rights aren’t absolute. In the appendix to chapter 4, they give examples of different conceptions of property rights. Without getting into the philosophy behind a property rights system, it’s clear that a conception of property rights has to answer four fundamental questions: What things can be privately owned? o Clearly not everything can be owned – nobody owns the ocean, you can’t own another person, etc. o Cultural artifacts o Ancient Jewish law – ownership over sold land was not permanent, it reverted to its ancestral owner after 50 years o Intangible property – copyrights, patents, trademarks What can (and can’t) an owner do with his property? o Again, not everything o Property rights can’t be absolute, because my exercising my rights might interfere with you exercising your rights – I want to sleep at home, you want to have a party next door o Typically, you can’t use your own property in a way that creates a nuisance to others o Many of the examples when we discuss Coase will have to do with limiting what a person can do with his property. o I own my kidneys, but I can’t sell one o If I own a building that has historical significance, I can’t necessarily destroy it or change it in certain ways. How are property rights established? o In the whaling example, what does it take to establish ownership? o And on the flip side, when can property rights be revoked? o Eminent domain – the government’s right to seize private property o In many cases when government wanted to encourage migration into new areas, free land, conditional on you farming it or developing it. Negligent landlords. What remedies are given when property rights are violated? o Rights – my right to use my property in certain ways – and prohibitions – other people can’t interfere – have no meaning unless they are enforced o So how do I get compensated if my property rights are violated? Answers to some of these may seem obvious, but they’re not always. For example: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21088150/ -7- One early, “classic” court ruling on property law: Pierson v. Post Decided in 1805 by the New York Supreme Court Post had organized a fox hunt, and was in pursuit of a fox Pierson appeared “out of nowhere,” killed the fox, and took off with it Post sued to get the fox back, saying that since he was chasing it, he owned it Lower court sided with Post; Pierson appealed the decision to the NY Sup Ct (Post and Pierson were apparently both wealthy, and pursued the case on principal or out of spite – both spent far more than the value of the fox in pursuing the claim) The fundamental question: when do you own an animal? I mention it here not because we care that much about when you establish possession of a wild animal, but because the court – both the majority and the dissenting opinion – were explicit about considering the economic effects their ruling would lead to Court ruled for Pierson – among other things, they say that: “If the first seeing, starting or pursuing such animals . . . . should afford the basis of actions against others for intercepting and killing them, it would prove a fertile source of quarrels and litigation.” That is, if the first to chase an animal owned it, there would be endless disputes and court cases; and so they favored a more “bright line” rule of ownership which would lead to fewer disagreements (They also point out that just because an action is “uncourteous or unkind” does not make it illegal) Dissenting opinion, however: a fox is a “wild and noxious beast,” and killing them is “meritorious and of public benefit” – Post should own the fox, in order to create incentive for fox hunting So, tradeoff: Pierson gets the fox Simpler rule Easier to implement Fewer disagreements Post gets the fox More efficient incentives (stronger incentive to pursue animals that may be harder to catch) Same tradeoff as Fast Fish/Loose Fish versus Iron-Holds-The-Whale. Fast Fish/Loose Fish is the simpler rule, and should lead to fewer disputes; and when it was good enough to work, it tended to be chosen. Iron-Holds-The-Whale is more complicated, should lead to more disputes, but is necessary in some cases (sperm whales) to create a good enough incentive. -8- Before we go about trying to answer these questions in detail, we begin with Coase. We said on Thursday that, despite its problems, we’ll generally be looking at the law with an eye toward efficiency When we consider property, and we’re worried about efficiency, the main question to ask is often simply, who gets to own what? Ronald Coase (1960), “The Problem of Social Cost,” gives the rather surprising answer: it doesn’t matter. That’s oversimplifying it a bit. What Coase says, which has become known as the Coase Theorem, is: In the absence of transaction costs, if property rights are well-defined and tradeable, voluntary negotiations will lead to efficiency. The initial allocation of property rights (who owns what to start with) will matter for distribution, but will not matter for efficiency. This is easiest to illustrate with an example we’ve already seen: my car. There’s a car, and, in the words of Cooter and Ulen, “the pleasure of owning and driving the car” is worth $3,000 to me, and $5,000 to you. Since the car’s worth more to you than it is to me, we know it’s efficient for you to have the car. (Assume there are no externalities – your neighbors don’t care.) If you start off with the car, then great – you have the car, there’s no reason for me to buy it from you, you end up with the car, and we get efficiency. If I start off with the car, then we clearly have an incentive to come to some arrangement. Property rights have to be well-defined – it has to be clear that it’s my car, and I have to be allowed to sell it to you. But as long as that’s the case, we should be able to reach some bargain – you give me $4,000, or maybe a bit more, or maybe a bit less – and I give you the car. So you end up with the car, which is efficient. The point is, regardless of who starts off with the car, you’re going to end up with it. I’d rather I start with the car – that way, I end up with a bunch of your money. You’d rather you start with the car – that way, you don’t have to pay me anything. But for efficiency, it doesn’t matter who starts with the car, we’ll achieve efficiency (you having the car) either way. -9- The key here is the absence of transaction costs. Basically, there can’t be any impediments to us reaching a private agreement If every time someone sold a used car, the buyer had to pay a huge tax to the government, the Coase theorem would fail Next lecture, we’ll discuss what some sources of transaction costs are; for now, just think of them as anything that gets in the way of us trading among ourselves. Now, the Coase theorem sounds pretty obvious when it comes to objects. If I own something, but it’s worth more to you, and there’s nothing to stop me from selling it to you, I guess I’ll end up selling it to you. Obviously. What Coase did, though, was apply this to rights, and situations with externalities, as well. Suppose I have an apartment, and you live next door. You want to have a party on Saturday. I hate noise, and don’t want you to. Well, the right to make noise is worth something to you. And the right to be undisturbed is worth something to me. If the right to make noise is worth more to you then the right to be undisturbed is worth to me, then it’s efficient for you to have the party. If the right to be undisturbed is worth more to me, it’s efficient for you not to have the party. What does Coase say? Coase says, think of these “party rights” as an object. As long as we know who starts off with these rights, and we’re allowed to buy and sell them, we’ll get efficiency no matter what. If I start off with the “party rights” – the right to be undisturbed – but they’re worth more to you, you can buy them from me Similarly, if you start off with the rights, but they’re worth more to me, I can buy them from you For distribution, who starts off with the rights matters – since they’re worth something, we’d both rather have them But who starts off with them doesn’t matter for efficiency – we’ll get to efficiency either way - 10 - In his paper, Coase begins with a different example Suppose that on adjacent tracts of land, there is a farmer and a cattle rancher The rancher’s cattle will occasionally stray onto the farmer’s land and eat some of the crops And the bigger the cattleman’s herd, the more damage will be done to the farmer’s crops First, consider what happens when the farmer has no recourse, that is, when the rancher is not liable for damage done by his herd When the rancher is deciding on the size of his herd, he weighs only the private costs and benefits, ignoring the incremental damage that a larger herd would do to his neighbor’s crops – that is, ignoring the externality he imposes So on the margin, this may lead him to a cattle herd that’s inefficiently large In addition, since he isn’t harmed by the damage done by his herd, he has no incentive to build a fence or to do anything else to rein in his herd, Next, consider what happens when the rancher is liable for any damage done by his herd Now, when he decides how big a herd to raise, he will consider the incremental damage done to his neighbor, since he has to pay for the damage; and he will consider actions that he can take to restrain his herd, if they are cheaper than paying for the damage But now there is no incentive for the farmer himself to take any steps to reduce the damage, such as o building a fence o planting less o planting less along the boundary between the two tracts of land o or planting crops that cows don’t like along the boundary o or any other steps that might also be cheaper than the damage done. Now, suppose that it’s cheaper for the farmer to fence in his crops, than for the rancher to fence in his herd When the rancher is not liable for damage done by his herd, this is what will happen But when the rancher is liable, the farmer will have no reason to build the fence; so the rancher might build his fence, which is more expensive So one allocation of legal liability seems to be more efficient than the other - 11 - But then Coase makes two major points: First of all, the problem is not just that the rancher is doing harm to the farmer; since if the rancher is made liable for the damage, or forced to restrain his herd, then it is instead the farmer who in a sense is doing harm to the rancher Coase refers to this as the “reciprocal nature” of the problem Thus, he rephrases the question in terms of efficiency instead of blame That is, he doesn’t ask, should the rancher be allowed to harm the farmer or not? Instead, he points out, either the rancher’s activities will harm the farmer, or the farmer’s presence, by restraining the rancher, will harm the rancher; so we should figure out which harm is greater And the second, more important point of Coase is that, in his words, as long as the pricing system works smoothly, that is, as long as there are not great costs and impediments that prevent the rancher and farmer from bargaining with each other and striking mutually beneficial deals, then they will negotiate themselves back into an efficient situation If it’s cheaper for the farmer to fence in his land rather than the rancher to fence in his herd, then the rancher will pay the farmer to do this, rather than incur the costs of the losses or build his own fence Or, if the rancher is not liable, the farmer will choose do this on his own If it’s cheaper for the rancher to reduce the size of his herd, he’ll do this on his own (because he’s liable), or because the farmer pays him to So as long as the rancher and farmer are allowed to bargain and come to mutually beneficial agreements, they will lead themselves to the efficient outcome (You can think of this as “creating a market for crop damage.”) Coase gives a number of other examples of situations with externalities, mostly in the area of nuisance law, and repeats the point that, regardless of who is initially held responsible for the harm, negotiation and trade will lead to efficiency from any starting point. Some of his other examples: An early English case of a building which was built in such a way that it blocked air currents from turning a windmill A building in Florida which cast a shadow over the swimming pool and sunbathing areas of a nearby hotel A doctor whose office was next door to a confectioner, who built a new examination room and found that the vibration from the confectionery’s machinery prevented him from listening to his patients’ chests through a stethoscope in that room A chemical manufacturer whose fumes interacted with a weaver’s products while they were drying after bleaching A house whose chimney no longer worked well after its neighbors rebuilt their house to be taller - 12 - In each example, he argues that, regardless of who is held to be liable, the parties can negotiate with each other and take whatever remedy is cheapest to fix (or endure) the situation. To quote Coase: “Judges have to decide on legal liability but this should not confuse economists about the nature of the economic problem involved. In the case of the cattle and the crops, it is true that there would be no crop damage without the cattle. It is equally true that there would be no crop damage without the crops. The doctor’s work would not have been disturbed if the confectioner had not worked his machinery; but the machinery would have disturbed no one if the doctor had not set up his consulting room in that particular place… If we are to discuss the problem in terms of causation, both parties cause the damage. If we are to attain an optimum allocation of resources, it is therefore desireable that both parties should take the harmful effect into account when deciding on their course of action. It is one of the beauties of a smoothly operating pricing system that… the fall in the value of production due to the harmful effect would be a cost for both parties.” - 13 -