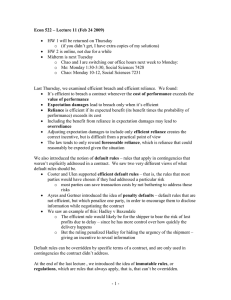

Econ 522 – Lecture 12 (Oct 16 2007)

advertisement

Econ 522 – Lecture 12 (Oct 16 2007) Last week, we asserted five economic purposes to contract law: enable cooperation by turning games with noncooperative solutions into games with cooperative solutions encourage efficient disclosure of information secure optimal performance (efficient breach) secure optimal reliance (although what’s actually done is rewarding “foreseeable” reliance) lower transaction costs by supplying efficient default rules for when gaps are left in contract terms, and efficient regulations (immutable rules) (We’ll get to a sixth today.) We discussed Ayres and Gertner, who give a different view of default rules: that default rules should not always be efficient, but should be designed in such a way as to give an incentive to disclose relevant information. (This is what was done implicitly in the Hadley v Baxendale decision – the shipper was not liable for the miller’s lost profits, since the miller did not tell him how urgently he needed the crankshaft delivered.) We wrapped up with examples of some regulations, or immutable rules. In particular, we looked at some situations in which a contract would not be held to be binding, even if both parties apparently wanted it to be binding at the time it was signed. Two were examples where the rationality of the parties was in question – when one of them was a minor, or insane. Two were examples where one of the players faced “dire constraints,” specifically, duress or necessity. It’s not that hard to argue against holding you responsible for promises made under duress or necessity based on notions of fairness and morality. The Friedman book (Law’s Order) tries to understand these in straight economic terms, and I think it’s worth a digression. Duress He begins with an example of duress. A mugger approaches you in an alley and threatens to kill you unless you give him $100. You don’t have $100 on you, but he says he’ll accept a check. When you get home, can you stop payment on the check? Or do you have to honor the agreement you made? Clearly, he wants the agreement to be enforceable; he’d rather have $100 than kill you. And if you believe he’ll kill you if you don’t give him the money, then you clearly want it to be enforceable as well. So making the contract enforceable seems to be a Paretoimprovement. So what’s the problem? The problem, of course, is that even if such a contract is a Pareto-improvement once you’re in the situation, making such contracts enforceable encourages more muggings, since it increases the gains. So refusing to enforce contracts signed under duress seems to trade off a short-term “loss” – the efficiency lost by ruling out some mutually beneficial trades – against creating less incentive for the bad behavior that put you in that situation in the first place. (The fact that there is a tradeoff implies that it may not be optimal to rule out enforceability under every instance of duress. For example, peace treaties can be thought of as contracts signed under duress – the losing side is facing the threat of continuing to battle a superior force. Most people agree that peace treaties being enforceable is a good thing. Peace treaties are clearly a good thing “ex post” – they make war less costly, by ending it more quickly. Perhaps by making war less costly, they encourage more wars – but it seems unlikely that this has much effect. It’s probably efficient for peace treaties to be enforceable, but for promises made to a mugger to be unenforceable.) Necessity However, the logic that tells us that contracts with muggers shouldn’t be enforced doesn’t work for contracts signed under necessity. You’re out sailing on your $10 million boat and get caught in a storm. The boat starts taking on water and slowly begins to sink. A tugboat comes by and offers to tow you back to shore, if you pay him $9 million. If not, he won’t leave you to die – he’ll give you and your crew a ride back to shore, but your boat will be lost. With duress, we argued that making the contract enforceable would encourage muggers to commit more crimes, which is bad. But here, making the contract enforceable would encourage tugboats to make themselves available to rescue more boats – so how is that a bad thing? In fact, Friedman points out that if we consider the tugboat captain’s decision beforehand – how much to invest in being in the right place at the right time – the higher the price, the better. The total gain (to all parties) from the tugboat being there is the value of your boat, minus the cost of rescuing it – say, $10,000,000 - $10,000 = $9,990,000. Allowing the tugboat to recover the entire value of the boat would make his private gain from rescuing you exactly match the social gain – which would cause the tugboat captain to invest the socially optimal amount in being able to rescue you! But on the other hand, consider your decision about whether to take your boat out on a day when a storm is a possibility. Suppose there’s a 1-in-100 chance of being caught in a storm; and if you are caught in a storm, there’s a one-in-two chance a tugboat will be there to rescue you. If he can charge you the full value of your boat, then when weighing the costs and benefits of going sailing that day, you consider a 1-in-100 chance of losing the full value of the boat. That is, in your analysis of whether it’s worth going sailing, you’ll include the 1/200 possibility the boat sinks, and the 1/200 possibility you pay its full value to an opportunistic tugboat captain – a total expected cost of $100,000. So you’ll only go sailing on days where your benefit is greater than $100,000. But when you go sailing and start to sink, half the time, your loss is the tugboat captain’s gain. The social cost of you sailing includes a 1-in-200 chance the boat is lost, plus a 1in-200 chance it has to be towed to shore; for an expected cost of $10,000,000 / 200 + $10,000 / 200 = $50,050. So efficiency says you should go out sailing whenever the benefit to you is greater than $50,050. So if the tugboat captain is able to charge you the full value of the boat, you will “undersail” – that is, in cases where your private gain from sailing is between $50,050 and $100,000, efficiency would suggest you should sail, but since the private cost outweighs the benefit, you choose not to. On the other hand, suppose the tugboat could only charge you the cost of the tow. Then the social cost of sailing would match the private cost to you - $50,050. This would lead you to go sailing exactly the efficient amount. Friedman, then, makes the following point. The same transaction sets ex-ante incentives on both parties; and the price that would lead to an efficient decision by one of them, would lead to an inefficient decision by the other. So, what to do? As Friedman puts it, “put the incentive where it will do the most good.” Somewhere in between the cost of the tow and $10 million is the “least bad” price – the price that minimizes the losses due to inefficient choices by both sides. If the tugboat captain is more sensitive to incentives than you are, the best price is likely closer to the value of the boat; if you respond more to incentives than he does, the best price may be closer to the cost of the tow. But regardless of the details, two things will generally be true: the least inefficient price is somewhere in the middle and there’s no reason for it to be the price that would be negotiated during the storm That is, once you’re caught in a storm, all the relevant decisions have already been made – you’ve decided whether to sail, the tugboat captain has decided whether to be out there looking for sinking sailboats. Those are like sunk costs – they don’t affect your bargaining position now. So there’s no reason that, if you bargained over saving your boat during the storm, you’d end up anywhere near that efficient price. On the other hand, there’s always the risk that bargaining breaks down and you refuse the tugboat captain’s offer, incurring a large social cost (the value of the boat minus the tow is lost). So from an efficiency point of view, it makes sense for courts to step in, overturn contracts that were signed under necessity, and replace them with what would have been ex-ante optimal terms. This takes away the need to bargain hard during the storm, ensuring that the boat is saved; and it creates the “least bad” combination of incentives. So that’s Friedman’s take on duress and necessity. (The same observation – that a single price creates multiple incentives, which cannot all be set efficiently – holds true in other areas too. We showed before that expectation damages set the incentive to breach the contract efficiently – that is, lead to efficient breach. However, Friedman gives the example that expectation damages set a different incentive incorrectly – the incentive to sign the contract in the first place! If you will owe expectation damages under circumstances that favor breach, the private cost of those circumstances is higher to you than the social cost, so you may forego some contracts that would be overall value-creating. Later on, we’ll come to a different type of damages which would lead to efficient signing decisions, but inefficient breach. Again, it’s impossible to set both incentives correctly at the same time. Later today, we’ll see the Peevyhouse case, which is an example of this.) Misinformation So that’s dire constraints. There are also four doctrines in contract law that excuse breach if a promise was made due to bad information: fraud failure to disclose frustration of purpose mutual mistake In the grasshopper example from day 1 of contract law, the seller of “a sure method of killing grasshoppers” defrauded the customer by deliberately tricking or misinforming him; the contract between them would not be enforced, so the customer would get his money back. Fraud violates the “negative duty” not to misinform the other party in a contract. In some circumstances, parties also have a positive duty to disclose certain information – but this is not always the case. In the civil law tradition, a contract may be void because you did not supply the information that you should have. In many common law situations, a seller is required to warn the buyer about hidden dangers associated with a product, such as the side effects of a drug. In the common law, however, there is not a general duty to disclose information that makes a product less valuable without making it dangerous. Under the common law, a used car dealer does not have to tell you every flaw about a car he is selling you, although he cannot lie about these faults if you ask him. (On the other hand, a new car comes with an “implied warranty of fitness” – the seller of a new car must return the purchase price if the car proves unfit to perform its basic function, transportation.) Fraud and failure to disclose are situations where one party is misinformed. There are also situations in which both parties to a contract are misinformed. When both parties base a contract on the same misinformation, the contract will often not be enforced based on the doctrine of frustration of purpose. An example of this comes from the English law treatment of the Coronation Cases. In the early 1900s, rooms in buildings along certain streets in London were rented in advance for the day of the new king’s coronation parade. The new king became ill, and the coronation was postponed. The renters, then, did not want the rooms, but some of the owners tried to collect the rent anyway. The courts ruled that a change in circumstance had “frustrated the purpose” of the original contracts, and refused to enforce them. Frustration of purpose would also presumably void the agreement if you won an auction for an expensive painting, and then you and the seller both discovered it was a forgery. When the parties to a contract base the agreement on different misinformation, it is a case of mutual mistake. One of our early examples featured a beat-up Chevy and a shiny new Cadillac. The seller believed he was negotiating the sale of the Chevy; the buyer thought she was negotiating the purchase of the Cadillac. In this case, the court would typically invalidate the contract based on mutual mistake and simply return the buyer’s money and the seller’s keys. In some cases, when monopoly (or some other circumstance) leads to parties agreeing to a very unequal contract, the court may refuse to enforce the contract on the basis of unconscionability. Unconscionability is defined as clauses or terms that are so unfair that they would “shock the conscience of the court.” The civil law tradition has a similar concept, called lesion. In both cases, courts may refuse to enforce a contract where one side is clearly being taken advantage of. The book gives the example of a customer signing a contract which allows a furniture seller to repossess all the furniture in his house if he is a single day late on a single payment on a single item. The court may find such a clause “unconscionable” and refuse to enforce it. Unconscionability tends to be invoked not in the usual circumstances of monopoly, but in “situational monopolies,” that is, particular circumstances that limit one’s choice of trading partners to a single person. This was the example in Ploof v Putnam – Ploof was sailing on a lake when a storm appeared, and Putnam was the only person who could give him safe harbor, becoming a monopolist in this situation even though he normally would not have been. Repeated Games Nearly everything we’ve done so far has assumed a one-shot interaction – that is, we’ve been assuming that the parties to a contract are only interested in maximizing their gain from that one particular contract, and are not concerned with any future interactions with the same partner. Of course, in many cases, this is not true. Suppose there’s a coffee shop near my house, and I go there several times a week. One day, I forget my wallet, and ask if I can pay them back the next day for a cup of coffee and a muffin. They say yes, and I show up the next day with the money. Why? Economists would say, The reason I pay them back is that I want to keep transacting with them in the future, and the value I expect to get from those future transactions is worth more to me than the $3 I could save by breaking my promise now. The reason they trusted me is that they expected this would be the case. From a theoretical point of view, repeated games can be very hard to analyze, because a lot of different things can happen. But one of the things that can happen is that we can cooperate in a repeated game, even if we could not cooperate in the same one-shot game. Let’s go back to the original agency game we did last week. You choose whether to trust me with $100, which I can double by investing it; and then I decide whether to keep the $200 or return $150 to you and keep $50 for myself. But now, suppose there is the possibility of playing the game more than once. In particular, suppose that each time we play the game, there is a 10% chance it’s the last time we play, and a 90% chance that we get to play again. Think about my incentives to repay your money or keep it for myself. If I keep it for myself, I get a payoff of $200; but then you’ll never trust me again, so that’s all I’ll ever get. On the other hand, if I give you back your $150, you’ll probably trust me again the next time, and the time after that, and the time after that (provided I keep returning it). So the value I expect to get out of the relationship is 50 + .9 X 50 + .9^2 X 50 + .9^3 X 50 + … = 50 / (1 - .9) = 500 > 200 So I’m much better off returning your money, since I’ll make more money in the longrun if you keep trusting me. The same thing can happen with a repeated version of the prisoner’s dilemma. Recall that in the one-shot prisoner’s dilemma, the only equilibrium was for both of us to rat on each other and go to jail for several years. However, if we expect to play the prisoner’s dilemma over and over, it turns out to be an equilibrium to both keep quiet. Actually, what turns out to be an equilibrium is for both of us to do the following: Keep quiet the first time we play As long as neither of us has ever ratted on the other, keep quiet Once either of us has ever ratted, I rat every time we play forever This is called a “grim trigger” strategy – we play a good (cooperative) strategy, but if either of us every rats, this triggers a “punishment phase” where we are unable to cooperate. The threat of moving to this punishment phase keeps us both quiet, even though either of us would gain in the short-term by ratting each other out. So in the prisoner’s dilemma, or the agency game, if the game will be played over and over, it’s possible to get cooperation. Similarly, in situations where contracts cannot be enforced, repeated interactions with the same parties can lead to voluntary cooperation. Even when you won’t always be transacting with the same person, transacting within a small community, where people are aware of your reputation, leads to a similar incentive. The Friedman book mentions an article by Lisa Bernstein on diamond dealers in New York. To quote: Buying and selling diamonds is a business in which people routinely exchange large sums of money for envelopes containing lots of little stones without first inspecting, weighing, and testing each one. The New York diamond industry was at one time dominated by orthodox Jews, forbidden by their religious beliefs from suing each other – making it a trust-intensive industry conducted almost entirely by people who could not use the legal system to enforce their agreements. While the industry had become more diverse by the time Bernstein studied it, dealers continue to rely almost entirely on private mechanisms to enforce contracts – in part for religious reasons, in part to maintain privacy, in part, perhaps, because those mechanisms functioned better than the courts. At the center of the system is the New York Diamond Dealers’ Club, which arranges private arbitration of disputes among diamond merchants. Parties to a contract agree in advance to arbitration; if, when a dispute arises, one of them refuses to accept the arbitrator’s verdict, he is no longer a diamond merchant – because everyone in the industry now knows he cannot be trusted. Similar arrangements exist elsewhere in the world and exchange information with each other. Presumably the amount diamond merchants are willing to risk on a single deal depends in part on how long the other party has been involved in the industry and thus how much he would lose if he had to leave it. Thus, Cooter and Ulen propose a sixth purpose of contract law: The sixth purpose of contract law is to foster enduring relationships, which solve the problem of cooperation with less reliance on the courts to enforce contracts. (We saw with the agency game that one way to allow for cooperation was to introduce enforceable contracts. Repeated interactions, or enduring relationships, give another way to get cooperation in what seems like a game with a noncooperative solution.) The textbook gives a couple of examples of how courts sometimes do this. For instance, by assigning legal duties to relationships that arise out of contracts – for instance, a bank has a fiduciary duty to its depositors which goes well beyond the terms they agree to on the account; a franchisee who runs a local McDonalds has certain duties to the franchisor. These duties are meant to encourage an enduring business relationship. Similarly, courts sometimes treat long-term business relationships differently, encouraging the parties to “repair the relationship” rather than simply ruling on the merits of the dispute. endgames However, there is a problem with enforcing agreements via reputation or repeated interaction. In the examples so far, we’ve assumed that we don’t know how long we’ll keep interacting, but that it might go on indefinitely. However, if there is a particular date when we know our relationship will be over for sure, this can lead to a problem. Suppose we are going to play the agency game once a month for five years – that is, we’re going to play 60 times. Clearly, getting $50 60 times is much better than getting $200 once, so it seems there should be no problem with getting me to return your money early on in the interaction. However, think about the problem from the other end. The last time we play, there’s no longer any future gain if I return your money, since we already know it’s our last time playing. Given that, you expect me to steal the money you give me in game #60, so you don’t lend me the money. But now think about game #59. We both know that we won’t cooperate in game #60 – that’s true regardless of what happens in game #59. So what happens here doesn’t affect future play – so once again I have no reason to return your money, so I keep it; and you expect this, so you don’t trust me. But now if we don’t expect to cooperate in game #59 or #60, there’s no reason for you to trust me in game #58. And so on. So in a finitely repeated game, cooperation can unravel from the back, and we can fail to cooperate form the very beginning! (People have done lab experiments – getting people (usually undergrads) to play the prisoner’s dilemma with each other for small cash payments. In finitely repeated games, people usually do choose to cooperate in the early stages, but not toward the end. The theory, however, predicts that we shouldn’t even get cooperation in the early stages of the game.) This is referred to in Cooter and Ulen as the “endgame problem” – once we know there is a finite end date to our interaction, cooperation can unravel. They discuss an example where this happened: the collapse of communism across much of eastern Europe in 1989. While communism was felt to be much less efficient than capitalism, the replacement of central planning with markets actually led to a decrease in growth rather than the anticipated increase. Why? Under communism, a lot of production relied on the black market, or the semi-legal gray market. Since these transactions weren’t protected by law, they relied on long-term relationships to accomplish cooperation. However, the fall of communism, and the uncertainty that came with it, upset these relationships, causing much important cooperation to break down. So while repeated interaction gives us a way to cooperate without relying on courts to enforce contracts, having a definite end date to the interaction can spoil it. Keep in mind, though, that to sustain cooperation, the game doesn’t have to go on forever; it just has be possible at each stage that it might continue. The probability the game is played again functions like a discount factor – you discount the future gains by the probability they will occur, but if the probability is reasonable, these gains may still be enough to sustain cooperation. Peevyhouse We said before that default rules are rules which hold when the contract leaves a gap; but which the parties are free to contract around. And we said that expectation damages were a good default rule, since they would lead to efficient breach. We never argued that expectation damages should be a mandatory rule – that is, we never said that parties should not be allowed to specify their own rule for breach. We also mentioned that a single transaction or price will set multiple different incentives, and it may be impossible to set all of them optimally. One interesting application of both these principles is the case of Peevyhouse v Garland Coal and Mining Company, decided by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma in 1962. Peevyhouse owned a farm in Oklahoma, and Garland contracted to strip-mine some coal on the property. The contract specified that Garland would take certain steps to restore the property to its previous condition after mining the coal. After mining the coal, Garland made no attempt to take these restorative steps, which it was estimated at trial would have cost $29,000. Peevyhouse sued for about that much ($25,000). The parties agreed during trial that everything else in the contract had been performed. The defendant introduced evidence that although the damage would cost $29,000 to repair, it lowered the value of the plaintiffs’ farm by only $300. (The “diminution in value” of the farm due to the damage was $300.) The original jury awarded Peevyhouse $5000 in damages, and both parties appealed to the Oklahoma Supreme Court – Peevyhouse saying this was less than the service that had been promised, Garland saying this was still more even than the total value of the farm after repairs. The OK Supreme Court reduced the damage award to $300. At first glance, this seems like a nice example of efficient breach – performing the last part of the contract would cost $29,000, and benefit the Peevyhouses by $300, so it is efficient to breach and pay expectation damages, which is what was awarded. However, the dissenting opinion noted that the coal company was well aware of what they were getting into when they signed the contract. Most coal mining contracts at that time contained a standard per-acre diminution payment, that the coal company paid instead of repairing the property. The Peevyhouses specifically rejected that clause of the contract during initial negotiations, and would not sign the contract unless it specifically promised the restorative work. The dissent argued that the Peevyhouses were therefore entitled to “specific performance” of the contract, that is, to have the restorative work completed as promised. As we mentioned before, expectation damages here would lead to efficient breach; but would not have led to efficient signing, as the Peevyhouses apparently would not have agreed to a contract they thought would low efficient breach. Clearly, the Peevyhouses have a right to their own property, and to attach terms to using it; and the dissent noted that circumstances had not changed since the contract was signed, so Garland should have known the approximate costs of the restorative work when they signed the contract. At least one scholar has claimed that the judges who decided Peevyhouse were incompetent or corrupt – one was later impeached, and others resigned – although others have disagreed. Still, it appears that the ruling here attempted to turn an efficient default rule – expectation damages – into a mandatory rule, that is, a rule that would be enforced even when it was not what the parties intended at the time of the contract. The case also, I think, gives a clear illustration of the competing forces of efficient breach and efficient signing, and the fact that no damage rule would lead to both.