First Responders Dr. Abdul-Monim Batiha Assistant Professor Critical Care Nursing

advertisement

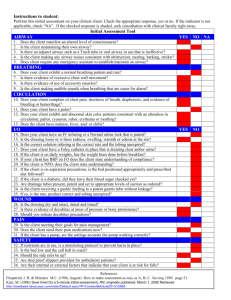

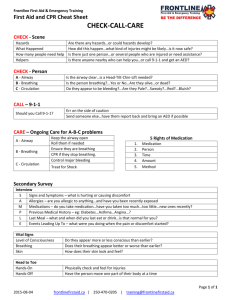

First Responders Dr. Abdul-Monim Batiha Assistant Professor Critical Care Nursing Philadelphia university Patient Assessment • • • • Scene assessment Primary survey Secondary Survey Reporting of data Scene Assessment Make a quick assessment of the overall situation at an accident scene. Concentrate on the big “big picture.” Consider three things: • Environment • Hazards • Mechanism of injury Look for anything that may threaten your safety and the safety of others, such as downed power lines, falling rocks, traffic, fire, smoke, etc. Do not move a casualty unless he or she is in immediate danger, If you must move the casualty, do so as quickly as possible. Mechanism Of Injury The mechanism of injury can alert you to the possibility that certain types of injuries may be present. For example, fractured bones are usually associated with falls and motor vehicle accidents, burns with fires, and soft tissue injuries with gunshot wounds. Remember, however, that for every obvious injury, there may be a number of hidden ones. Primary Survey The primary survey is conducted once dangers at the scene have been neutralized. It is the first step in the physical assessment and consists of the following: • Check of level of consciousness (LOC) as you approach the patient. • Check of DABC (Delicate spine, Airway, Breathing, and Circulation) • Rapid body survey (RBS) for external blood loss and deformities While conducting the primary survey, you may discover lifethreatening emergencies such as obstructed airways, respiratory difficulties, external bleeding, and obvious shock. Treat these problems immediately. For your protection, wear disposable gloves whenever you might be handling blood, body fluids, or secretions. Perform A Primary Survey To perform a primary survey, you must be able to do the following: • Assess level of consciousness (LOC) using the AVPU method. • Manage a delicate spine. • Open and maintain the airway. – Clear obstructions from the patients mouth. – Open the airway. – Correctly use an oral airway for unconscious. – Suction the mouth cavity if required. – Place unconscious patients and patients with compromised airways in the recovery position and monitor breathing. Continued • Assess and manage the patient’s breathing. – Determine when a patient is not breathing adequately. – Use a pocket mask to ventilate patients with inadequate breathing. – Ventilate an infant using a pocket mask, connected to oxygen, and mouth-to-mask ventilation's. – Use the bag-valve-mask-oxygen reservoir unit to ventilate patients with inadequate breathing. • Assess and manage the patients circulation. • Perform a rapid body survey (RBS). – Perform a rapid body survey. – Give oxygen at high flow (10 L/min) with a standard face mask. – Describe the pathophysiology of hypoxic drive and the management of a COPD patient. Assess Level of Consciousness (LOC) • Check for LOC as you approach the patient. • The A,V,P,U method is a short and simple way to assess the LOC: A - patient is Alert V - patient responds to Verbal stimuli P - patient responds to Pain (Use a trapezoidal squeeze to administer a painful stimulus.) U - patient is Unresponsive to verbal and painful stimuli A change in the level of consciousness is the first sign of a brain injury or other serious medical conditions. Manage A Delicate Spine Always assume that the patient has a neck or spine injury(delicate spine). You may rule it out after considering the mechanism of injury, bur always check for a delicate spine if the patient must be moved. If you suspect that the patient has a delicate spine, do the following: • Approach the patient from the head. • Tell the patient, “If you can hear me, don’t move.” • Stabilize the head in the position found. • Do not move the patient unless absolutely necessary to maintain an an open airway. When using the various grips remember to use the principles of STABLE to UNSTABLE Open and Maintain The Airway Airway management involves three things: • Opening the airway • Maintaining the open airway • Helping the patient breathe effectively (ventilation) Look, listen, and feel for the movement of air at the mouth and/ or nose. After an injury, a patient’s airway may become closed or blocked by teeth, the tongue, or foreign objects. “check for 5 seconds” Continued Before taking steps to open the airway, make sure you have ruled out a delicate spine or protected the neck. The technique you use will depend on whether or not the mechanism of injury indicates a delicate spine. To manage the airway, you must be able to do the following: • Clear obstructions from the patient's mouth. • Open the airway. • Correctly use an oral airway for unconscious patients. • Suction the mouth cavity if required. • Place unconscious patients and patients with compromised airway in the recovery position and monitor breathing. Clear Obstructions From The Patient’s Mouth And Throat. Make sure your patient’s airway is clear before trying to open it. Remove foreign materials such as broken teeth, vomitus, fluid and mucus before attempting any further treatment. Use a crossedover finger technique to open the patient's mouth, and do a visual check. Crossed-over Finger Technique Opening The Airway Open the airway after clearing foreign materials form the mouth. The tongue can easily act as a lid, closing down onto the back of the throat and making breathing impossible. To open your patient’s airway, you must lift the tongue up and off the back of the throat. NO NECK INJURY: • Use the Head-Tilt/Chin-Lift Method Do not use this procedure on any patient with neck or spinal injuries. NECK INJURY SUSPECTED: • Use the jaw thrust or modified jaw thrust If you suspect a neck injury, take care not to move the neck. Head-Tilt/Chin-Lift Modified Jaw Thrust Method Oral Airways Once the airway passage is clear and open, you must keep it open, especially if the patient is unconscious and cannot do it himself or herself. The oral airway (oropharyngeal airway), a hard plastic tube, is the ideal tool for this. Inserted correctly, it prevents the tongue from falling back and blocking the airway. Oral Airways For Unconscious Patients Moving Patients A general principle for First Responders is that patients should be cared for in the position found. This principle is based on the assumption that certain conditions or injuries (such as a neck fracture in an unconscious patient) can be hidden so that it is missed during initial assessment, and unnecessary movement may make the situation worse. However, there are three situations in which you, the First Responder, will have to move the patient: • Repositioning the patient to manage immediate ABC’s. • Moving patients as quickly as possible out of hazardous areas. • Rescuing and transporting patients. Repositioning The Patients To Manage Immediate ABC’s Many patients are found in unusual or difficult positions. It may be necessary to move them in order to effectively assess or manage their ABC’s. If you must move a patient, follow these principles: • Moves are best done with the help of two or more people. • Although managing the ABC’s is always a priority, try to minimize movement during urgent repositioning. • Movement of the neck and spine is potentially more dangerous than moving an extremity. • In an awake patient, increased pain with movement should limit your repositioning. Positioning The Patient In most cases, positioning of the patient is determined by patient comfort. If possible, the patient should be left in the position found. However, if moving the patient results in better patient care, consider the following options: • Semi-sitting – Shortness of breath; obese patients; chest pain. • Supine – Suspected neck injuries; patient with no radial pulse; hip fractures. • 3/4 Prone or Recovery Position – All unconscious patients with no neck injury. – All patients with airway problems that cannot be controlled by suctioning. Suction Suctioning the mouth cavity is another procedure used to keep the airway clear. Secretions and other debris are removed by applying negative pressure through a hollow tube. If you do not remove the debris, you may force it into the patient’s lungs during ventilation. Assess And Manage The Patient’s Breathing A patient may be breathing on his or her own but not doing so adequately. Do not wait for respiratory arrest before ventilating the patient.(below 10, and over 30). To assess and manage the patient’s breathing, you must be able to do the following: • Determine when a patient is not breathing adequately. • Use a pocket mask to ventilate patients with inadequate breathing. • Ventilate an infant using pocket mask, connected oxygen, and mouth-to-mask ventilation's. • Use the bag-valve-mask-oxygen reservoir unit to ventilate patients with inadequate breathing. Determine When A Patient Is Not Breathing Adequately A patient is not breathing adequately if he or she has fewer than 10 respirations per minute and/ or shows some or all of the following signs of hypoxia (low oxygen level in the blood): • • • • • • • • • • agitation irritability drowsiness headache decreased level of consciousness rapid pulse labored breathing abdominal breathing bluish skin color irregular heartbeat BVM The bag-valve-mask-oxygen reservoir (BVM) unit allows you to ventilate a patient by moving enriched, oxygenated air into the lungs and removing carbon dioxide. The unit consists of the following: • oxygen reservoir • a bag • a non-return valve(to prevent rebirthing) • an anesthetic-type mask of various sizes (the pocket mask may also be used with this unit) • an inlet for oxygen delivery Circulation - Radial Pulse Circulation - Carotid Pulse Causes of Cardiac Arrest • • • • • heart attack electric shock drowning asphyxiation sensitivity reaction Compression Rates • One person adult CPR: 15 compressions 2 ventilation • Two person adult CPR: 5 compressions 1 ventilation • One person child CPR: 5 compressions 1 ventilation • Two person child CPR: 5 compressions 1 ventilation • One person infant CPR: 5 compressions 1 ventilation Perform A Rapid Body Survey (RBS). The rapid body survey will help you to locate and expose injury sites, stabilize fractures, and control bleeding. You should be able to accomplish the following: • Perform a rapid body survey. • Give oxygen at high flow (10 L/min) with a standard face mask. • Describe the pathophysiology of hypoxic drive and the management of a COPD patient. Rapid Body Survey Check for bleeding, deformity, and your patient’s response to pain by systematically running your hands over and under the following: • head and neck • chest and abdomen • back • lower extremities • upper extremities You should take no more than 30 seconds to perform a rapid body survey. It should be interrupted only long enough to provide intervention for life-threatening injuries. Oxygen Flow Rates • 5 Litres per minute – COPD Patients (No Trauma) • 10 Litres per minute – All trauma patients – Medical emergencies • 15 Litres per minute – Smoke and/ or gas inhalation – Carbon monoxide poisoning Oxygen Delivery Masks Bag-Valve-Mask (BVM) – Assist patients patients with inadequate respiration's. – Hyperventilate unconscious patients with head injuries. Pocket Mask – CPR-on-the-move. – Infant ventilation's. – when resuscitation from BVM does not create an effective seal. Non-Rebreather Mask – Victims of smoke and/ or gas inhalation. – Victims of carbon monoxide poisoning Full Face Mask – Patients with adequate respiration's. Oxygen As a first responder, you should use a standard face mask to give oxygen at 10 L/min to: • All trauma patients • All medical patients except those with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Oxygen therapy for the non-traumatic COPD patient is 5 L/min through a standard adult oxygen mask. But at a 10 L/min flow for traumatic COPD patient’s. COPD Patients In normal people, the breathing reflex is triggered by high level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the blood. Patients with emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and chronic asthma may have a condition know as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). They retain CO2 and thus have a chronically high level of this gas. Their breathing reflex is triggered only when the oxygen level in their blood is low. This mechanism is known as hypoxic drive. By giving COPD patients oxygen, you may suppress their breathing reflex. Give the patient with COPD, 5 L/min through a standard adult oxygen mask. Closely monitor the patient’s respiratory rate, depth, and volume. Assist the patient’s ventilation's if necessary. Perform A Secondary Survey The purpose of a secondary survey is to identify problems that, while not immediately lifethreatening, may threaten the patient’s survival if left undetected. The secondary survey consists of the: • Medical history (chief complaint and history of chief complaint) • Vital signs (LOC, pulse, respiration's, and skin colour and temperature) • Head-to-toe physical examination (if time permits) The information you gather here will be vital for the patient’s later care. You should be able to report it accurately and concisely to ambulance personnel when they arrive. Chief Complaint The chief complaint is what the patient says is wrong with him or her. Record and report it using the patient’s own words. This will help you avoid interpreting what was said, which may obscure or change the nature of the problem. Most chief complaints are characterized by pain or abnormal function. Find out what is bothering the patient most. For example, a victim of a motor vehicle accident may have an obvious leg fracture but his chief concern may be,”I can’t breath.” This may help you discover an unsuspected chest injury. History Of The Chief Complaint The history of the chief complaint examines the chief complaint in greater detail. Get a description of the events that caused the chief complaint. If pain is the chief complaint, use the PQRST method to help you organize your questioning. Ask the following: • Position of the pain. • Quality of the pain. • Does the pain Radiate?. • Severity of the pain. • Timing of the pain. P - Position – Where is it located? Can you point to it? Q - Quality – What does it feel like? Is it sharp, dull, throbbing, or crushing? R - Radiation – Does it radiate anywhere? or Does it stay in one place or move around? Does anything relieve it? What makes it worse? S - Severity – How would you rate the pain on a scale of 1 to 10 – (10 being the worst)? T - Timing – When did it start? What brought it on? Have you had it before? How long does it last? Guidelines When Interviewing A Patient • Allow the patient to answer in his or her own words. • Avoid suggesting answers. (“What provoked the pain?” Not “Does the pain come after exertion?”) • Use open-ended questions. Avoid asking questions that can be answered with yes or no. • To pinpoint responses, give the patient alternatives. (Does the pain stay in one place or does it move around?) • Reassure the patient frequently. Vital Signs Baseline vital signs are one of the most important aspects of patient assessment. They are taken after the primary survey and the medical history. Based on them, ambulance personnel and receiving hospital staff can tell whether or not the patient’s condition is deteriorating. As a First Responder you should record the following: • LOC (using the AVPU method) • Skin - colour, condition and temperature • Pulse - rate, rhythm, and strength • Respiration's - rate, rhythm, and volume (quality) Monitor the LOC, take the pulse, and count the respiration's every five minutes. Check whether the patient’s skin is: • cool or warm • moist or dry • pale or normal in colour • condition Recording And Reporting Data Recording and reporting data is the last major component of the patient assessment model. Your report will help guide the ambulance personnel and hospital staff in treating the patient. Report your findings orally to responding ambulance personnel. Your oral report should include the following: • Mechanism of injury • Chief complaint • History of chief complaint • LOC, pulse, respiration's, and skin colour and temperature • Treatment given • All relevant physical findings Follow up your oral report with a completed copy of the First Responder Report. (within 24 hours of the incident) Manage An Unconscious Medical Patient Assess And Manage Victims Of A Heart Attack Manage A Patient Experiencing A Heart Attack Assess and Manage Victims of Respiratory Emergency People experience difficulty breathing for many reasons. Some conditions that cause respiratory distress are: • Asthma - spasms occurring in the airways of the lungs, causing wheezes. • Pneumonia - infection of the lungs. • Bronchitis - inflammation of the bronchi in the lungs. • Emphysema - a chronic decrease in the lung’s ability to expel air due to cell damage If respiratory distress is not relived, respiratory failure and respiratory arrest may follow. Signs and Symptoms of Respiratory Distress • • • • • • • • • Laboured, Noisy Breathing Irregular Rate, Rhythm, and depth of breathing Unusual Pulse Rate and Character Flaring Nostrils Pursed Lips Numbness or Tingling in Hands ands And Feet Blue or Grey Lips, Skin, or Nail Beds Confusion, Hallucinations Desire to Lean Forward Manage A Patient Experiencing A Respiratory Emergency Assess and Manage Stroke Victims • Strokes are sudden brain damage caused by blocked or ruptured arteries. A severe stroke may cause death; less severe one may impair certain bodily functions. Because each of the two hemispheres in the brain controls the opposite side if the body, damage in one hemisphere causes weakness or paralysis in the opposite side of the body. Signs and Symptoms of a Stroke • Change in level of mental ability • Decreased consciousness • Change in personality • Trouble understanding speech • Convulsions • Severe headache • Loss of vision, or dimness • Pupils unequal in size • • • • Drooping mouth, eyelids Inability to speak Respiratory distress Loss of bladder or bowel control • Nausea and/ or vomiting • Paralysis or weakness on one or both sides of the body(face, arm, or leg) • Rapid, strong pulse Manage a Patient Experiencing a Stroke Do the following: • Maintain an open airway and provide O2 . • Keep the patient at rest. – Turn an unconscious patient 3/4 prone onto the affected side. – Place a conscious patient in the position with head and shoulders slightly elevated to relieve pressure on the brain. Continued • Protect the patient from injury when being lifted or moved or during convulsions. • Do not allow the patient to become overheated. • Do not give the patient anything by mouth. Assess and Manage Patients With Seizures A seizure is a sudden change in sensation, behavior, muscle activity, or level of consciousness. It is not a disease but a symptom of an underlying problem. The most common cause of seizure is epilepsy. Epileptic have recurrent seizures, but the cause is not always known. Focal seizures begin with convulsive movements in one part of the body. Generalized seizures may begin suddenly and spread rapidly. Continued Other causes of seizures are: • head trauma • infection and high fever • tumors • hypoglycemia (too little sugar or too much insulin) • stroke • poisoning Signs and Symptoms of a Generalized Seizure • The patient has sudden loss of consciousness and collapses. • The patient’s body stiffens. • Convulsions occur, jerking all parts of the body. • Breathing is laboured. • There is frothing at the mouth. • After convulsions, the patient's body relaxes completely. • The patient becomes conscious, but is very tired and confused. Manage A Patient Experiencing A Seizure • Place the patient on the floor or ground if the patient is not already down. • Check the patient’s ABCs. Intervene if necessary to maintain an open airway or to ventilate the patient. If an oral airway is not tolerated, do not force any other objects between the patient’s teeth while the seizure is going on. • • • • Administer high flow O2 at 10 L/ min. Loosen tight clothing. Do not hold the patient during the convulsions. Protect the patient from injury and from onlookers. Remove any potentially harmful objects. • After the seizure, turn the patient on his or her side (3/4/ prone recovery position). • If the seizure resulted from high fever, cool the patient by removing excess clothing.