Designing and Implementing Standardized Clinical Encounter Forms

advertisement

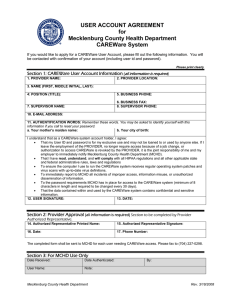

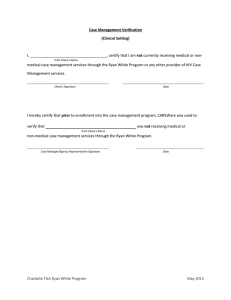

Designing and Implementing Standardized Clinical Encounter Forms and Modules to Support HIV Care Geneva- March 2004 John Milberg, US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau, Rockville, MD USA The Challenge • Design and implementation: How do you get useful and timely information into and out of a data collection system designed to track a multi-faceted, chronic condition • Whether it’s a paper form or a computerized information system, PDA, or phone-based system, the HMIS should help: – The provider of care in their daily activities; – The larger public health system and the ability to monitor HIV care and supplies on a population basis System Functions and Outputs • Enable care providers to readily collect, use and report information on main aspects of HIV care, TB treatment and follow-up, pregnancy/ PMTCT. etc. in a format that is useful to them and to others providing clinical support. • Track prescriptions(and fees?) and drug stocks at point of care • “Deliver data to and from central monitoring points” (WHO): Provide mechanism for data to be entered into or transmitted to a central location so that treatment and care information can be used for quality of care management and oversight • Provide clinical support for treatment decision-making (real-time vs. delayed) If caregiver is uncertain how to treat, how do they get support? Can they get it in real-time? Do they need clinical decision support in real-time in all instances? Standards to do What? • Provide treatment and ensure quality of care • Track: • – Drug prescriptions and inventories, lab results – Adverse events/side effects, reasons for changing therapy – Adherence – Clinical Course (OIs, body weight, “stage” of illness, etc.) – TB prophylaxis/Treatment – Pregnancy history/PMTCT – Quality of Life Report aggregate information—for WHO, PEPFAR, TGF, etc. Establishing common standards in data collection and reporting can reduce burden to providers AND improve capacity to monitor care Standards to do What? • Assess quality of care and needs: What does the individual patient require? – Who should start ARVs, TB, and other medications? – Who is failing and should have medications changed? – Who has missed visits and requires follow-up? – Who requires supportive care for adherence, transportation, mental health Barriers to Implementation • To ensure minimum standards of care and adequate patient follow up, do care providers have the – Time, – Adequate training and – Flexible data management and reporting tools? • Are information systems--whatever form--able to help with these client-specific monitoring tasks and many other broader functions (assessing trends overall, producing reports, exporting data to a central administrator). WHO Chronic Care with ARV Therapy: Translating Complicated Treatment Protocols into Simple Clinical Information and HIV Care Delivery Systems “Unaided human decision makers do not possess the consistency of behavior or the accuracy of perception necessary for the consistent delivery of recommended therapies” Source: Morris AH. Developing and Implementing Computerized Protocols for Standardization of Clinical Decisions. Annals Internal Medicine 2000; 7 (132). Desired Features of Paper Forms • Attributes: – Clear and as simple as possible for caregiver to follow treatment protocol – Outlines essential alerts, warnings, and reminders on treatments (e.g. Don’t prescribe EFV in pregnant women; don’t start ARVs until certain clinical criteria are met, Ruling out active TB, etc) – Design of form should allow ease of data entry into HMIS upon completion, allowing for clinical overviews to be fed back into clinic (timely quality assurance) Limitations of Paper Forms • Difficult to clearly convey all decision rules in the form at time of care- becomes complicated quickly • If not ultimately entered into a computer, extremely difficult and cumbersome to summarize data for reports and quality monitoring **What has been learned from other systems, in particular TB, that can help in the design of HIV care information systems? (see www.tbcindia.org) Electronic HMIS: Lessons from CAREWare • Standardized data core for tracking longitudinal clinical, service, and social support information • Ability to customize the application without programming • Ability to rapidly generate reports for daily patient care and monitoring overall quality of care • While decision support rules currently not built into software, patient-specific quality of care reports easily generated that are used to monitor and manage quality of care-produced before patient visit • Ease of producing required reports Getting Data in—and Out: CAREWare Examples Getting Data in—and Out: CAREWare Examples Getting Data in—and Out: CAREWare Examples Getting Data in—and Out: CAREWare Examples Getting Data in—and Out: CAREWare Examples Examples of Clinical Support in CAREWare Examples of Clinical Support in CAREWare:Patient Scheduler • Who has a visit today or this week? • Clinical summary of expected patients • Produce reports of missed visits CAREWare: Limitations • Lacks a simple one page interface for data entry that mirrors a standard clinical encounter in typical ARV treatment setting • Lacks simple alerts and reminders (if used in real-time); relies on user running encounter reports. • But…This should change soon! CAREWare: Future Developments • Networkable version (in .NET) that will also allow for disconnected clinic sites to export data (“store and forward” ) • Collaboration, such as that promoted by this meeting, will clarify essential features to develop for international version. • Collaborate with specific clinical sites to pilot test (e.g. in Uganda, South Africa) • Incorporate HIV clinical decision support developed by Columbia University (HIV Tips) Focused and Timely Clinical Information • Caregivers will likely have only a short time to spend with each patient. In this setting, how can the HMIS help prepare for the clinical encounter so that it is focused and informed by essential, up to date medical history information necessary to make appropriate clinical decisions? • What is feasible given: Limited training and experience Lack of time; Overburdened staff Lack of other resources Getting Data In and Information Out • Can clinical data be used and retrieved by care providers? Onsite, on-time? – Who will key enter the data? – Who will have the time/skills to review and use the data? • Can data be transmitted to another (central) location where care givers with greater training can offer clinical assistance (decision support) – Provide clinical summaries via some method of Telehealth (phone call, email, website); make treatment recommendations (either in real-time or not) or help establish a longer-term treatment plan • Can data be analyzed centrally to enable quality of care management, and support public-health decision-making, at the district, provincial or national level)? Possible Solutions and Clinic Feedback: Clinical Decision Support and Quality Management • Produce treatment plans prior to patient clinic visit. (But how produced/by whom?) • Focus and tailor the clinical decision support so it can be conveyed to the clinical provider and the patient clearly, and in a short period of time. (Onsite vs. some form of Telehealth) Possible Solutions and Clinic Feedback: Technical Assistance and Support • Provide data management support, especially if data entry is not occurring in a timely fashion • Provide data “use” support to ensure appropriate treatment information is getting fed back to the clinic site and that its use is understood; Create benchmarks/ treatment and service goals • Hire clinical and data consultants (MIS corps?) to provide training, periodic oversight; Provide support to sites with high rates of ARV treatment failures (regimen changes) and examine clinic process: Why is this occurring in this site? What aspects of care can be improved? (See Frieden and Khatri, Impact of national consultants on successful expansion of effective TB control in India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003; 7:837-41.)