Chapter 3: Religion and Gender Differences

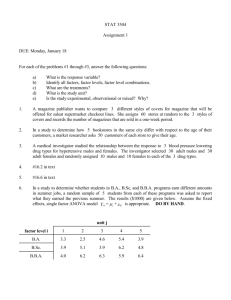

advertisement