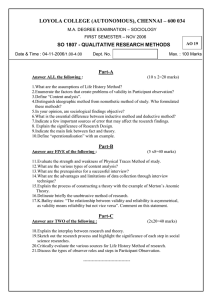

What do we know about assessment & what should Chris Rust

advertisement

What do we know about assessment & what should we do about assessment? Chris Rust Assessment is vitally important influence on student learning Assessment influences both: Cognitive aspects - what and how Operant aspects - when and how much (Cohen-Schotanus, 1999) But in the UK, we do it badly! • QAA subject reviews (90s) • National Student Survey (05-) • “…serious grounds for concern” about assessment methodologies and statistical practices (IUSS, 2009, p116) And in Australia… “Students can, with difficulty, escape from the effects of poor teaching, they cannot (by definition if they want to graduate) escape the effects of poor assessment. Assessment acts as a mechanism to control students that is far more pervasive and insidious than most staff would be prepared to acknowledge. It appears to conceal the deficiencies of teaching as much as it does to promote learning. If, as teachers, we want to exert maximum leverage over change in higher education we must confront the ways in which assessment tends to undermine learning.” (Boud, 1995, p35) Two major purposes of assessment Assessment of learning (summative): -measuring what, and how much has been learnt; differentiating between students; gatekeeping; accreditation; qualification; license to practice Assessment for learning (formative): -experiential; learning from mistakes; diagnostic; identifying strengths and weaknesses; feedback; feed-forward Arguably failing at both Summatively: (Un)reliability - locally and nationally Unscholarly practices in marking, focused on numbers Grade inflation, declining standards & dumbing down (In)validity Programme design – whole may not be the sum of the parts Formatively: Encouraging inappropriate learning behaviours Too much summative and not enough formative assessment/not enough effective feedback Prog. design – lack of linkage and integration Reliability Hartog & Rhodes (1935) Experienced examiners, 45% marked differently to the original. When remarked, 43% gave a different mark Hanlon et al (2004) Careful and reasonable markers given the same guidance and the same script could produce differing grades; Difference between marks of the same examiners after a gap of time Unscholarly practices in marking, usually involving numbers! “A grade can be regarded only as an inadequate report of an inaccurate judgement by a biased and variable judge of the extent to which a student has attained an undefined level of mastery of an unknown proportion of an indefinite amount of material” (Dressel, 1957 p6) “Comparability within a single degree programme in a single institution should in principle be achievable. However, the extensive evidence about internal variability of assessments makes it seem unlikely that it is often achieved in practice” (Brown, 2010) UK Degree Classifications QAA (2007) Quality Matters: The classification of degree awards “Focusing on the fairness of present degree classification arrangements and the extent to which they enable students' performance to be classified consistently within institutions and from institution to institution….” (p1) “The class of an honours degree awarded…does not only reflect the academic achievements of that student. It also reflects the marking practices inherent in the subject or subject studied, and the rule or rules authorised by that institution for determining the classification of an honours degree.” (p2) “...it cannot be assumed students graduating with the same classified degree from different institutions, having studied different subjects, will have achieved similar standards; it cannot be assumed students graduating with the same classified degree from a particular institutions, having studied different subjects, will have achieved similar standards; and it cannot be assumed students graduating with the same classified degree from different institutions, having studied the same subject, will have achieved similar standards.” (p2) In a traditional chemistry course, half of the students who solved test problems couldn't explain the underlying concepts. (Mary Nakhleh, Purdue, 1992) In pre-med physics, 40% doing well on conventional tests could not answer conceptual questions (Eric Mazur, Harvard, 1998) In mechanics, about half of the students do relatively well at the exam but relatively poorly in a test of their understanding (Camilla Rump, DTU, 1999) Problem of validity - too much assessment of questionable validity “The research shows concurrently that students often show serious lack of understanding of fundamental concepts despite the ability to pass examinations.” [Rump et al. 1999, p 299, & cites over 10 other studies] “Even grade-A students could only remember 40 per cent of their A-Level syllabus by the first week of term at university” [600 students tested in their first week of term at five universities ] (Harriet Jones, Beth Black, Jon Green, Phil Langton, Stephen Rutherford, Jon Scott, Sally Brown. Indications of Knowledge Retention in the Transition to Higher Education. Journal of Biological Education, 2014) Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) Manageability (resources) Reliability Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) Manageability (resources) (Knight et al) ? too much of our practice is focused here. Over-emphasis on summative & reliability Reliability Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) assessing airline pilots Manageability (resources) Reliability Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) assessing airline pilots Manageability trade-off, dependant on context (resources) Reliability Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) if more purely formative assessment, could increase authenticity Manageability (resources) Reliability Dependability: one-handed clock (Stobart, 2008) Construct validity (authenticity) if more purely formative assessment, could increase authenticity Manageability (resources) if less summative, assessment could/ should aspire to be here Reliability Problems of Course Design 1. Atomisation and validity - Module/unit L.O.s vs Programme L.O.s Module outcomes, filtered by assessment criteria, are turned into marks, and marks are turned into credit but what does this accumulated credit actually represent? What validity does it have? Are the programme outcomes ever truly assessed? Problems of Course Design 1. 2. Atomisation and validity - Module/unit L.O.s vs Programme L.O.s Module outcomes, filtered by assessment criteria, are turned into marks, and marks are turned into credit but what does this accumulated credit actually represent? What validity does it have? Are the programme outcomes ever truly assessed? Slow learning, complex outcomes, & integration Slowly learnt academic literacies require rehearsal and practice throughout a programme (Knight & Yorke, 2004) ‘Slow time … necessary for certain kinds of intellectual and emotional experience, for the production of certain forms of thought, and for the generation of certain kinds of knowledge’ (Land 2008, p15, citing Eriksen) ‘This quest for reliability tends to skew assessment towards the assessment of simple and unambiguous achievements, and considerations of cost add to the skew away from judgements of complex learning’ (Knight 2002, p278) Problems of Course Design 1. 2. Atomisation and validity - Module/unit L.O.s vs Programme L.O.s Module outcomes, filtered by assessment criteria, are turned into marks, and marks are turned into credit but what does this accumulated credit actually represent? What validity does it have? Are the programme outcomes ever truly assessed? Slow learning, complex outcomes, & integration Slowly learnt academic literacies require rehearsal and practice throughout a programme (Knight & Yorke, 2004) ‘Slow time … necessary for certain kinds of intellectual and emotional experience, for the production of certain forms of thought, and for the generation of certain kinds of knowledge’ (Land 2008, p15, citing Eriksen) ‘This quest for reliability tends to skew assessment towards the assessment of simple and unambiguous achievements, and considerations of cost add to the skew away from judgements of complex learning’ (Knight 2002, p278) Where there is a greater sense of the holistic programme students are likely to achieve higher standards than on more fragmented programmes (Havnes, 2007) Problems of Course Design The achievement of high-level learning requires integrated and coherent progression based on programme outcomes 1. 2. Atomisation and validity - Module/unit L.O.s vs Programme L.O.s Module outcomes, filtered by assessment criteria, are turned into marks, and marks are turned into credit but what does this accumulated credit actually represent? What validity does it have? Are the programme outcomes ever truly assessed? Slow learning, complex outcomes, & integration Slowly learnt academic literacies require rehearsal and practice throughout a programme (Knight & Yorke, 2004) ‘Slow time … necessary for certain kinds of intellectual and emotional experience, for the production of certain forms of thought, and for the generation of certain kinds of knowledge’ (Land 2008, p15, citing Eriksen) ‘This quest for reliability tends to skew assessment towards the assessment of simple and unambiguous achievements, and considerations of cost add to the skew away from judgements of complex learning’ (Knight 2002, p278) Where there is a greater sense of the holistic programme students are likely to achieve higher standards than on more fragmented programmes (Havnes, 2007) Problems of Course Design 3 – Encourage a Surface approach “The types of assessment we currently use do not promote conceptual understanding and do not encourage a deep approach to learning………Our means of assessing them seems to do little to encourage them to adopt anything other than a strategic or mechanical approach to their studies.” (Newstead 2002, p3) “…students become more interested in the mark and less interested in the subject over the course of their studies.” (Newstead 2002, p2) Many research findings indicate a declining use of deep and contextual approaches to study as students’ progress through their degree programmes (Watkins & Hattie, 1985; Gow & Kember, 1990; McKay & Kember,1997; Richardson, 2000; Zhang & Watkins, 2001; Arum & Roksa, 2011) If graded, students more likely to take a surface approach & much less likely to see the task as a learning opportunity (Dahlgren, 2009) Nine Principles of Good Practice for Assessing Student Learning (AAHE, 1996) 1. The assessment of student learning begins with educational values. 2. Assessment is most effective when it reflects an understanding of learning as multidimensional, integrated, and revealed in performance over time. 3. Assessment works best when the programs it seeks to improve have clear, explicitly stated purposes. 4. Assessment requires attention to outcomes but also and equally to the experiences that lead to those outcomes. 5. Assessment works best when it is ongoing not episodic. 6. Assessment fosters wider improvement when representatives from across the educational community are involved 7. Assessment makes a difference when it begins with issues of use and illuminates questions that people really care about. 8. Assessment is most likely to lead to improvement when it is part of a larger set of conditions that promote change. 9. Through assessment, educators meet responsibilities to students and to the public. (http://www.fctel.uncc.edu/pedagogy/assessment/9Principles.html) 11 conditions under which assessment supports learning: 1 (Gibbs and Simpson, 2002) 1. Sufficient assessed tasks are provided for students to capture sufficient study time (motivation) 2. These tasks are engaged with by students, orienting them to allocate appropriate amounts of time and effort to the most important aspects of the course (motivation) 3. Tackling the assessed task engages students in productive learning activity of an appropriate kind (learning activity) 4. Assessment communicates clear and high expectations (motivation) 11 conditions under which assessment supports learning: 2 (Gibbs and Simpson, 2002) 5 Sufficient feedback is provided, both often enough and in enough detail 6 The feedback focuses on students’ performance, on their learning and on actions under the students’ control, rather than on the students themselves and on their characteristics 7 The feedback is timely in that it is received by students while it still matters to them and in time for them to pay attention to further learning or receive further assistance 8 Feedback is appropriate to the purpose of the assignment and to its criteria for success. 9 Feedback is appropriate, in relation to students’ understanding of what they are supposed to be doing. 10 Feedback is received and attended to. 11 Feedback is acted upon by the student 7 principles of good feedback practice (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) Helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards) Facilitates the development of reflection and selfassessment in learning Delivers high-quality information to students about their learning Encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning Encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem Provides opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance Provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape the teaching Assessment for learning: 6 principles or conditions (McDowell, 2006*) A learning environment that: 1. Emphasises authenticity and complexity in the content and methods of assessment, rather than reproduction of knowledge and reductive measurement 2. Uses high-stakes summative assessment rigorously but sparingly, rather than as the main driver for learning 3. Offers students extensive opportunities to engage in the kind of assessment tasks that develop and demonstrate their learning, thus building their confidence and capabilities before they are summatively assessed 4. Is rich in feedback derived from formal mechanisms such as tutor comments on assignments and student self-review logs 5. Is rich in informal feedback. Examples of this are peer review of draft writing and collaborative project work, which provide students with a continuous flow of feedback on ‘how they are doing’ 6. Develops students’ abilities to direct their own learning, evaluate their own progress and attainments an support the learning of others *http://northumbria.ac.uk/ 16 indicators of effective assessment in Higher Education (Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Australia, 2002) 1. Assessment is treated by staff and students as an integral and prominent component of the entire teaching and learning process rather than a final adjunct to it. 2. The multiple roles of assessment are recognised. The powerful motivating effect of assessment requirements on students is understood and assessment tasks are designed to foster valued study habits. 3. There is a faculty/departmental policy that guides individualsユ assessment practices. Subject assessment is integrated into an overall plan for course assessment. 4. There is a clear alignment between expected learning outcomes, what is taught and learnt, and the knowledge and skills assessed - there is a closed and coherent ‘curriculum loop’. 5. Assessment tasks assess the capacity to analyse and synthesis new information and concepts rather than simply recall information previously presented. 6. A variety of assessment methods is employed so that the limitations of particular methods are minimised. 7. Assessment tasks are designed to assess relevant generic skills as well as subjectspecific knowledge and skills. 8. There is a steady progression in the complexity and demands of assessment requirements in the later years of courses. 16 indicators of effective assessment in Higher Education (contd.) 9. There is provision for student choice in assessment tasks and weighting at certain times. 10.Student and staff workloads are considered in the scheduling and design of assessment tasks. 11.Excessive assessment is avoided. Assessment tasks are designed to sample student learning. 12.Assessment tasks are weighted to balance the developmental (‘formative’) and judgemental (‘summative’) roles of assessment. Early low-stakes, low-weight assessment is used to provide students with feedback. 13.Grades are calculated and reported on the basis of clearly articulated learning outcomes and criteria for levels of achievement. 14.Students receive explanatory and diagnostic feedback as well as grades. 15.Assessment tasks are checked to ensure there are no inherent biases that may disadvantage particular student groups. 16.Plagiarism is minimised through careful task design, explicit education and appropriate monitoring of academic honesty. [at http://www.cshe.unimelb.edu.au/assessinglearning/05/index.html] A new emerging assessment culture (Bryan & Clegg, 2006) Active participation in authentic, real-life tasks that require the application of existing knowledge and skills Participation in a dialogue and conversation between learners (including tutors) Engagement with and development of criteria and selfregulation of one’s own work Employment of a range of diverse assessment modes and methods adapted from different subject disciplines Opportunity to develop and apply attributes such as reflection, resilience, resourcefulness and professional judgement and conduct in relation to problems Acceptance of a limitation of judgement and the value of dialogue in developing new ways of working Assessment 2020 – 7 propositions (Boud, D. and Associates, 2010) Assessment has most effect when: 1. assessment is used to engage students in learning that is productive 2. feedback is used to actively improve student learning 3. students and teachers become responsible partners in learning and assessment 4. students are inducted into the assessment practices and cultures of higher education 5. assessment for learning is placed at the centre of subject and program design 6. assessment for learning is a focus for staff and institutional development 7. assessment provides inclusive and trustworthy representation of student achievement A Marked Improvement – six essential elements (HEA, 2012 – based on ASKe Assessment Manifesto, 2007) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. A greater emphasis on assessment for learning rather than assessment of learning A move beyond systems focused on marks and grades towards the valid assessment of the achievement of intended programme outcomes Limits to the extent that standards can be articulated explicitly must be recognised A greater emphasis on assessment and feedback processes that actively engage both staff and students in dialogue about standards Active engagement with assessment standards needs to be an integral and seamless part of course design and the learning process in order to allow students to develop their own, internalised, conceptions of standards and monitor and supervise their own learning The establishment of appropriate forums for the development and sharing of standards within and between disciplinary and professional communities Standards can only be established through a community of assessment practice “Consistent assessment decisions among assessors are the product of interactions over time, the internalisation of exemplars, and of inclusive networks. Written instructions, mark schemes and criteria, even when used with scrupulous care, cannot substitute for these” (HEQC, 1997) Rust C., O’Donovan B & Price., M (2005) Social-constructivist assessment process model Rust C., O’Donovan B & Price., M (2005) Social-constructivist assessment process model Rust C., O’Donovan B & Price., M (2005) Social-constructivist assessment process model What we Know…About Assessment – eBook Free download from Oxford Centre for Staff & Learning Development Publications at: http://shop.brookes.ac.uk/browse/extra_info.asp? prodid=1392