Background Reading for “How to Spot a Tyrant”

advertisement

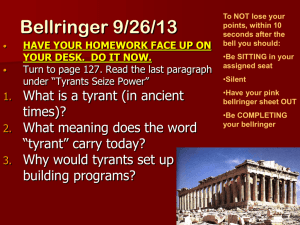

Background Reading for “How to Spot a Tyrant” “Tyrant” (tyrannos) was not always a fearful word, and “freedom” (eleutheria) was not always associated with democracy. The two shifts in ideas were gradual and simultaneous. As the people of ancient Athens invented democracy, they altered the meanings of the words. They showed tyrants on the stage of their theater as a reminder to themselves of what they wanted to keep at bay. Democracy requires freedom, and freedom means an end to tyranny. So it was important for the ancient Atheninas to understand what it is to be a tyrant. In grasping that, they would come tio understand what was most precious in their new democracy. Following are excerpts from a recent book by Paul Woodruff. 1 A tyrant is a monarch who rules outside the law, who came to power without the support of law, who is afraid of the people he rules, and who is therefore unable to trust anyone else’s advice. Moreover, a tyrant lets power go to his head; convinced that he knows everything, he believes he does not need to listen to anyone else’s advice. A tyrant may not always be abusive to the people he rules; he may have their best interests at heart. But his fear prevents him from deliberating freely; it warps his judgments, and the bad decisions he makes out of fear may destroy him or weaken the city. The End of Tyranny in Athens: A Sexual Predator Angers the People Sex will bring down the younger of the two tyrants of Athens, Hipparchus. He and his brother inherited power from their father, Pisistratus, 13 years earlier. Now Hipparchus has fallen in love with Harmodius, but Harmodius has a lover already. And this lover, Aristogiton, is prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice for the boy. Harmodius has not yet grown a beard, but he is strong enough to wield a sword. The tyrant thinks he can get away with anything. After all, his family has ruled Athens for two generations, during which the city has prospered. Taxes are light, business is good, new buildings are going up, and poets are flocking to Excerpts from “Freedom from Tyranny (and from Being a Tyrant),” Chapter 3 of Paul Woodruff’s First Democracy: The Challenge of an Ancient Idea (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). Author’s explanatory comments added in brackets. For more about the ancient sources, go to the original book or ask in the Classics Library. Translations are by the author. 1 the city. All the signs that Hipparchus can see tell him that he and his brother are popular rulers. No one has the courage to tell them otherwise. Hipparchus thinks he can get away with anything, and now he wants to get away with the beauty of this boy. We must imagine that he has had others before Harmodius; sexual predators usually have a record, and Hipparchus must have been successful. Until now. Harmodius spurns him, and then, when the tyrant does not take no for an answer, the boy rejects him a second time. Hipparchus cannot let this insult pass. He decides to attack the boy through his young sister. He bides his time until there is to be a religious festival that features a procession of young girls, daughters of citizen families. Then, just as the procession is forming, he has Harmodius’ sister thrown out on the grounds that her family’s claim to citizenship does not hold up. The public humiliation is too much for Harmodius and his lover. For the honor of the boy’s family, for the young girl’s honor, and for the honor of the boy — for all of this, and perhaps for freedom too — they slay the tyrant. It is the ultimate sacrifice; Harmodius is slain by the tyrant’s bodyguards; Aristogiton is captured, tortured, and killed. Hipparchus’ older brother rules on for a few years, but the charm of the family rule is ended, and a Spartan expedition will depose the last tyrant of Athens in 510 BCE, two years before the Athenian people are given their first taste of power in the new democracy. [This version of the story is due to the ancient historian Thucydides.] Proudest of Athenian monuments, the two lovers stood in marble for centuries thereafter, larger than life, brandishing their swords. They are heroic figures, splendid in bare muscles, fierce of eye. To the Athenians they were the image of freedom. They knew that the road to freedom begins with sacrifice. When the Persian king asked the people of Samos for tribute, they asked Aesop for advice. He replied: “Chance shows us two roads in life; one is the road of freedom, which has a rough beginning that is hard to walk, but an ending that is smooth and even; the other is the road of servitude, which has a level beginning, but an ending that is hard and dangerous.” Freedom v. Tyranny: [Ancient Texts] This is freedom: To ask, “Who has a good proposal He wishes to introduce for public discussion?” And one who responds gains fame, while one who wishes Not to is silent. What could be fairer than that in a city? And besides, when the people govern a country, They rejoice in the young citizens who are rising to power, Whereas a man who is king thinks them his enemy And kills the best of them and any he finds To be intelligent, because he fears for his power. How then could a city continue to be strong When someone plucks off the young men As if he were harvesting grain in a spring meadow? Why should one acquire wealth and livelihood For his children, if the struggle is only to enrich the tyrant further? Why keep his young daughters virtuously at home, To be the sweet delights of tyrants . . . ? I’d rather die than have my daughters wed by violence. (Euripides’ Suppliant Maidens, lines 438-455) No one sleeps well in a tyranny. Because the tyrant knows no law, he is a terror to his people. And he lives in terror of his people, because he has taught them to be lawless. The fear he instills in others is close cousin to the fear he must live with himself, for the violence by which he rules could easily be turned against him. Do you think anyone Would choose to rule in constant fear When he could sleep without trembling, And have exactly the same power? Not me. Why should I want to be Tyrant? I’d be insane . . . (Creon, in Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, lines 584-589) And tyrants do not have friends they can trust: For this plague always comes with tyranny: That the tyrant does not trust his friends. (Prometheus in Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, lines 224–25) Symptoms of Tyranny [These symptoms are highlighted in the ancient Greek theater, whenever a tyrant is shown on stage.] 1. A tyrant is afraid of losing his position, and his decisions are affected by this fear. 2. A tyrant tries to rise above the rule of law, though he may give lip service to the law. 3. A tyrant does not accept criticism. 4. A tyrant cannot be called to account for his actions. 5. A tyrant does not listen to advice from those who do not curry favor with him, even though they may be his friends. 6. A tyrant tries to prevent those who disagree with him from participating in politics. The Rise of a Tyrant Tyranny comes on a people painlessly at first, bringing an end to disorder, and promising comforts that people want. Many ordinary Athenians at first favored the tyrant Pisistratus. But their lawgiver Solon had seen tyranny coming, and he warned the people about where their ignorance would lead: From a cloud come snow and hail, powerfully, But thunder comes from bright lightning. The destruction of a city comes from great men, and the people Fall through ignorance under the slavish rule of one man. It’s not easy for one who flies too high to control himself Afterwards, so now is the time for the people to take thought. But the Athenians welcomed Pisistratus and gave in to his request for armed bodyguards. Such a request was the clear sign of a tyrant in those days; a legitimate leader would not fear for his life among his own citizens: If you have felt grief through your own fault Do not put the blame for this on the gods: You yourselves increased the strength of these men When you gave them guards . . And the Athenians were beguiled by the future tyrant’s promises, not noticing how his actions were eroding their freedom: Each of you follows the footprints of this fox, And you all have empty minds, For you watch only the tongue of the man, his slippery speech, But you never look at what he actually does. The story is simple and has often been repeated in history: A troubled people welcome a strong man to power, because he promises order and comfort. But the cost of tyranny is exorbitant. Order and comfort without freedom—that, after all, is the condition of sheep that are being fattened for slaughter. Ordinary Athenians understood this metaphor very well, and some came to see that it perfectly expressed their condition under the tyrants. Should we accept tyranny in order to have efficient government? Tyranny is too high a price to pay for efficiency, and inefficiency can actually be a good thing. In the conditions of ignorance in which governments actually function, inefficient leadership often provides a margin of safety—it slows the process by which bad ideas may become policy. Distrust of leadership is the best defense of democracy, as Greek popular speakers understood. As for defending individual tyrants, this is like defending the weather. A string of good days should not lull us into relying on the weather. The tyrant Pisistratus may have had his good days, and likewise his sons, but there was no more controlling them than there is controlling the weather. Tyrants may do things that we want done at the start, but in the long run there is nothing to stop them from doing whatever they want done. We should trust the judgment of the Athenian people. After two generations of rule by tyrants they had a horror of tyranny. They had reasons. Courage Democracy is not enough. Parties in a democracy can be tyrannical, and so can an entire democratic state, if it has an empire. These are disturbing thoughts. In 416 BCE, at a time of general peace, the Athenians sent an army to add the tiny island of Melos to their empire. The attack was preemptive, because Melos might soon side with Sparta; it had given some support to Sparta in the past. And the attack was a deterrent, because some parts of the empire were always on the edge of revolt, and they needed to be reminded of Athenian power and ruthlessness. The Athenians were afraid that if they did not conquer Melos, they would appear to be too weak to defeat a rebellion. In Melos, the leaders on both sides came together in a parley. The Athenian leaders told the leaders of Melos that they must surrender if they wanted to survive. The alternative was conquest, slavery for the women and children, and death for the men of the city. The leaders of Melos insisted on justice. They chose to fight, with the result that the Athenians had predicted. Athens took the city, killed the men, and enslaved the women and children of Melos. The parley had been a disaster. Neither side got what it wanted. Athens wanted the clean surrender of a thriving city; Melos wanted to maintain its autonomy. Athens got a desert, and Melos lost everything. Both sides are to blame for the failure of the parley. The leaders of Melos were afraid to put the issue to a vote of their people; the people of Melos would surely have sacrificed their leaders in order to secure the autonomy and democratic freedom that Athens offered them so long as they paid tribute to Athens. At the same time, the leaders of the Athenian army were afraid to make any concessions to Melos, for fear that any concession would be taken as a sign of weakness. This was a disaster for Athens as well as for Melos. It gave a boost to the propaganda that Athens was tyrant over its empire. It put the Athenians on the wrong moral foot in the second part of their great war with Sparta (as they had not been in the first). It did nothing to secure the empire, and seems in some ways to have weakened it. Later, when Athens was in trouble, and could no longer frighten the members of its empire, it depended not on fear, but on a loyalty, and this luckily did survive in a few places. In the fight against tyranny—and against being a tyrant—nothing matters more than courage. Courage was what was missing at the parley at Melos. The leaders of both sides were defeated by their own fears. In any negotiation, where there is a strong conflict of interest, we risk a tyrannical solution unless both sides can set aside their fears and bring courage to the negotiating table.2 A view of tyranny from the Christian era Compare Shakespeare’s treatment of this theme in Winter’s Tale. There, the king accuses his wife of infidelity and is so sure he is right that he refuses to listen to any of her defenders and he goes so far as to declare that the oracle’s word is false (Act 3, Scene 2). The god’s vengeance is immediate—the Queen dies and so does her son. An older woman, Paulina, berates the king: But, O thou tyrant! Do not repent these things, for they are heavier Than all thy woes can stir; therefore betake thee To nothing but despair. A thousand knees Ten thousand years together, naked, fasting, Upon a barren mountain, and still winter In storm perpetual, could not move the gods To look that way thou wert. Shakespeare’s vision is Christian, however, and unlike that of Sophocles it has room for divine clemency. Through no good work of his own, the tyrant will be reclaimed. Read more about Melos in Thucydides’ History, Book 5, translated in Paul Woodruff, Thucydides on Justice, Power, and Human Nature, Indianapolis 1993. 2