Document 17530564

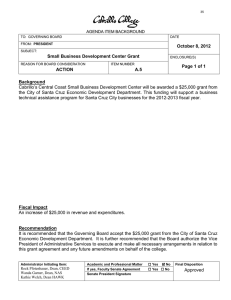

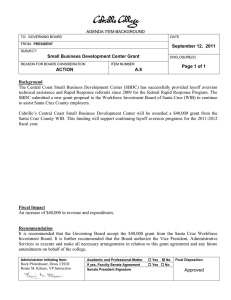

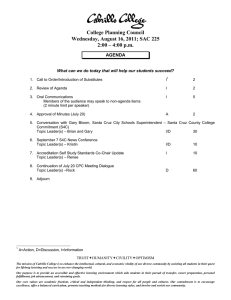

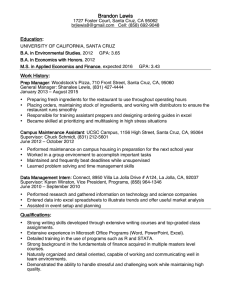

advertisement