[Session 3, July 31, 2007] HENLEY [Begin Tape 4, Side A]

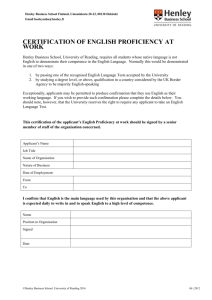

advertisement

![[Session 3, July 31, 2007] HENLEY [Begin Tape 4, Side A]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/017530540_1-921f72ef5b345f1cc3b7b3cc6895a7b4-768x994.png)

[Session 3, July 31, 2007] HENLEY [Begin Tape 4, Side A] PRINCE: Hello, it’s Tuesday July 31, 2007. I’m Lisa Prince, back at the Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection Center in Sacramento with Jim Henley, retiring manager. This is our third interview on behalf of the City of Sacramento for the Old Sacramento Historic District Oral History Project. Good morning Jim. HENLEY: Good morning Lisa. PRINCE: How are you today? HENLEY: I’m just fine. PRINCE: Good, good. I wanted to clarify one point of our last conversation. We were discussing you’d gone to work in Old Sacramento, you were doing historic research, and working on the buildings and you were working with or in conjunction with DeMars and Wells, the architecture firm hired by, was it Candeub and Fleissig? HENLEY: Well, DeMars and Reay were hired by Candebu and Fleissig. DeMars and Wells, which is the successor firm was hired by the Redevelopment Agency to continue the architectural work after Candueb and Flessig. PRINCE: After their master plan. HENLEY: Yes. PRINCE: Okay. I just wanted to clarify who you were working with – who hired you and I know you had been working with Aubrey Neasham but how did that work out, who was it you were working for at that point? HENLEY: Well, I was hired by the city; it’s kind of a strange relationship because it really wasn’t, as we would call an employee/employer relationship at the time. They called me a contract employee which later was deemed probably not legal, and it was a couple, three years later that they changed the designation to regular city employee, but the Commission was kind of an unusual character at that time in every other aspect of the city … PRINCE: When you say the Commission, are you talking about the Historical Landmarks Commission? HENLEY: The Historical Landmarks Commission. PRINCE: Okay, so that’s who you were working with or through? HENLEY: Well, this is – I’m working for the city, the Commission is a city commission … PRINCE: Okay. HENLEY: … and it’s doing work with that commission and the Commission is unusual in that it’s an appointed body by the City Council, but under the city charter all employees are responsible to the city manager – there’s a separation of powers there. And it’s the city manager’s responsibility to submit budgets and things like that to the council but this time it was done differently. The city council would appoint a council member to sit with a committee or commission and they together would draw up a budget and submit it to the council, sort of bypassing the city manager. And so, in a sense, even though I was a city employee, who I was reporting to, was a little bit confused. Was I reporting to the Commission? Was I reporting to that council member? Was I reporting to Aubrey – who actually hired me? That was sort of up to me to figure out and I very quickly decided that Aubrey was the lead and so I would follow him as my supervisor, and no one else seemed to care, so that’s how it came to be what it is. PRINCE: That worked out okay with everybody? HENLEY: Seemed to work out fine with everybody. PRINCE: So then, was Aubrey Neasham, was he answering to the city council, or working through the Redevelopment Agency, or? HENLEY: Well, Aubrey’s role is equally sort of confusing. He truly was a consultant, he never was an employee of the city, in fact he was at one point an employee of the state in State Parks, and a contractor to the Commission or the city for consulting services and was acting as the staff person to the Commission at the same time he was a State Parks employee, and at that same time he also had a company called Western Heritage Inc. which was his company. And he put it together essentially to do historic research and historic projects and he was the consultant to Candeub and Fleissig for the history part of the report through Western Heritage. So he sort of had his foot in all pots of water at the same time. PRINCE: Hmm, that’s very interesting. Can you just review a little bit what your specific duties were when you were first there and how it changed as you went along. I know that Aubrey Neasham had gone, he was gone in, what three years after you started or two years? HENLEY: Well, he sort of semi retired about three years afterwards. But he stayed around as a part-time consultant for another couple of years, at least, and then he did really pull out completely. When I came to work we had a – we, meaning the city – had a contract with the Redevelopment Agency to provide historic services for the Old Sacramento Project. What was going on at that point is the master plan by Candueb had been accepted and it was determined that the next step would be to refine all of the drawings and the research that had been done for the master plan into schematic studies of the facades of these buildings so that you could have some drawings and some historical information to attach to a contract or contracts for the development of the building or buildings in Old Sacramento when you got a developer. PRINCE: So this was the package that the developer would receive? HENLEY: That’s correct. It would define which building, what time period, and what the history of that building was. Well, most of the background research had been done before I came. Aubrey had two or three students – maybe as many as four or five at some point that were working with him at doing research. I knew most of them but I didn’t know them well because most of them had started to leave about the time I came. But it became real apparent that there were some gaps in the research, and so in my job, I started to do some original research but the majority of my time was working with DeMars and Wells staff in reviewing what they were drawing, interpreting what they should be seeing in the photographs as they transmitted it. That quickly got to be that there needed to be some organizational structure to this and so we started to create files for each of these buildings and we accumulated the photographs and the graphics that were known about each building and we tried to start to define the logic of how we chose which building to be restored to which time period. That was my job for about three years. PRINCE: Now did you, of course there was some buildings that were going to be restored in their place … HENLEY: Right. PRINCE: … but, am I right to say that a large amount of the buildings were reconstructed? HENLEY: Oh, I would say that forty percent, or more of the buildings were reconstructions, but probably more than half of them were existing buildings. That would change a little bit because at least three buildings collapsed during the process of restoration. PRINCE: Was that when they were being worked on? HENLEY: In two cases it was when they were being worked on. One case was while waiting for work to be done. Another two or three buildings had partial collapses, which they were able to lose a wall and continue to restore the rest of the building. So that’s about the ratio, and there is a small number of what we classified – we classified all the buildings in three categories: restorations, reconstructions, and relocations. And it was before I came, in the Candeub study that they determined that there would be certain relocations. And it was determined that the relocation buildings would be located at the edge of the historic district, on the north and the south end. There are several reasons for that – one, they didn’t want to mess with the central part of the district, and two, the peripheral edges of the district, the buildings that were there were twentieth century buildings and they felt they could easily dispense with them and infill with these relocations. And all those relocations came from under freeway – they were all part of the mitigation: the Big Four building; the Rialto, D.O. Mills; Fig buildings on the L street side – those are relocation buildings. PRINCE: So those were actually dismantled and moved to … HENLEY: They were in varying packages from literally dismantling and saving the brick and every single piece that they could and reconstructing it like in the case of the Big Four buildings – the Huntington, Hopkins Hardware store and the Stanford Brothers store – to the other end where the Rialto, D.O. Mills, Fig buildings are, they used historic brick that were dismantled from under the freeway but not necessarily from those specific buildings and they used some cast iron details and things that were salvaged but it’s much more like a reconstruction than a restoration. You know, it’s not a dismantle, pick it up, move it over set it down. PRINCE: This was part of, you say the mitigation so it was sort of the ultimate compromise between the opposing parties: the preservationists that opposed the freeway from the very beginning, didn’t want the freeway on the Sacramento side at all, and the Redevelopment Agency, and by this time the city council that was pushing for this route by this time. So they had agreed that, I guess it was the Daly plan that had, that wanted this route and that had agreed to save some but not all of the buildings and create this historic zone, but the freeway would still go through what the opponents considered the heart of the city. HENLEY: Yeah. I think as I understood the battle, and again, most of it was long over by the time I came, but as I understand the fight the preservation community was pretty unified in wanting the freeway out of Sacramento – over on the West Sacramento side. I think that at some point they came to realize that it probably couldn’t happen, that it was going to be in Sacramento. And so the preservation community and what we would maybe call the environmentalist movement type people today started to look at what they could salvage versus total victory – what can we get out of this? How much can we save? So they started to work towards some compromises and the ultimate compromise that came out of it was that serious bulge that occurs to make Old Sacramento have, as Neasham would put it, a full Second Street with buildings on both sides of the street. He didn’t want that freeway so close that there would be no east side of Second Street. PRINCE: So that was also compromised by the Daly Plan that had wanted the freeway to go right between Second and Third that would wipe out the east part of Second Street, so they bulged it in towards the east even further than they had originally intended. HENLEY: I think so, and I think that – when you say Daly Plan I think you’re talking about the Leo Daly Plan that the city had commissioned. PRINCE: Yeah. HENLEY: I really think that that may be giving it a name that it doesn’t deserve because I think all these routes were determined by the Division of Highways, they were not determined by Leo Daly … PRINCE: I see, yeah. HENLEY: I think Leo Daly looked at them and said this is the preferable one. PRINCE: That’s what it was, it was the Leo Daly consulting firm out of San Francisco that the city had hired to do this study and they came up with that route being the most favorable for all interests involved. HENLEY: One of the things that came out of this is, at least when I arrived, to me it looked like the preservation community was still essentially intact, that it had survived this trauma of the freeway and maybe was stronger than it had been before because it had learned to organize a little bit, but, in hindsight looking back at it I think in fact what happened is some people took their marbles and went home. And we never heard from them again. They removed themselves from the movement and any active involvement in it. Others said, “Okay, we won this, now what can we do with it?” And started to – that’s the group that I tended to know and that’s the group that I tended to work with the most. PRINCE: Who were some of those people? HENLEY: Oh, there were some old families. One that stuck around the Commission a long time would be somebody like Don Rivett, his father, Dexter, or his brother Dexter, they go back – they had a building in Old Sacramento, they go back to 1849. There were some people from Native Daughters [of the Golden West], a gal named Audrey Brown that was around for a long time. Gee, you know a lot of these names have failed me now, because they’re dead and I haven’t dealt with them for a long time. There were several commissioners that were very active in the movement for a long time. There was a guy who was the head of the state fair marketing group, he was their public relations guy, a guy named, oh man, I just lost his name – a great big, tall guy over six foot six, and he was very active. He used to go around and speak to every community club and everything about, “Now that we have this, how do we make it work, how do we get it moving, how do we fund it?” He was kind of a loud, vibrant kind of a guy and I don’t think he seriously meant this by any means but he used to go around and say, “Well you know, Old Sacramento will fall down waiting for Redevelopment to do it. All I want you to do is let me have one gambling establishment, and one house of ill repute and I’ll pay for the whole thing!” [Laughter] And he used to go around and say, “That’s part of the history of Old Sacramento.” PRINCE: He was right. HENLEY: He was right about that to some degree. But oh, you know, that worked really well when he’d go to a lot of these little clubs around town and people would giggle and they’d remember his talk, you know, he had nice slides to go with it. PRINCE: So did he garner much support in this process? HENLEY: Freddie Heitfelt was his name. PRINCE: Freddie Heitfelt? HENLEY: Freddie Heitfelt. Oh yeah, he garnered a lot of support and he stuck around for pretty close to ten years I would say but he was around until about 1970. And then I think his age kind of took its toll, and he sort of retired. PRINCE: He got to see a little bit … HENLEY: Yeah, he was around when the Morse building was built, so I know that. Yeah, he bought the vision, hook, line, and sinker that Neasham put in that painting. He saw that activity in the street. I give Freddie a lot of credit because I think that Freddie understood intuitively what no one else has understood about Old Sacramento. PRINCE: Which was … HENLEY: And that is with all the effort we’ve put into it with restoring and building those buildings, no matter how well-restored they are, that argument is sort of superfluous to the other side of the coin, and that is by restoring all those buildings, all you’ve created is a skeleton. If you believe in the image of the picture, there’s life there, and Freddie wanted that life to have an historical ambiance. He wanted history to be told down there and so he was the first person I recognized that saw that there were two sides to this coin. You not only had to restore buildings but you had to bring some life to it. And that’s what we failed to do in Old Sacramento. We failed to do the interpretation; we failed to do the cultural side of the project. We just put the bones in place, there’s no flesh on them. PRINCE: Ahh, yeah. Yeah, that’s a very good point and I would think that maybe that came about because there was such a focus on the buildings, just as artifacts or – why do you think that was overlooked in the beginning? HENLEY: It’s probably the same reason that people write histories of communities based on events and famous people and physical actions like completing a railroad or doing a transcontinental stage route, or a telegraph line, or the discovery of gold. Those are the traditional ways we deal with our history and it takes a little while for people to start thinking about the cultural side of it. What – beyond those events is there to this story? And that usually is the last thing to happen, at least in a historic district. You can’t – if you’re going to have a historic district you’ve got to have the skeleton in place, you’ve got to build the buildings or restore the buildings, or preserve the buildings, or what ever you’re going to do – then it’s about what you do with them after that is done is what’s important. And in many ways that’s about community history in general, we tend at first to anchor the community down by the events and the personalities, the “important” personalities in quotes, and after a while we get beyond that and we start to want to talk about communities and we want to talk about cultural movements and actions and interactions, and what is the impact of technology on people rather than just talking about the technology, what’s going on with the people? PRINCE: What’s going on with them and what were their motivators and their mindsets and all the interconnections of the different personalities from the smallest to the largest, in quotes? HENLEY: Old Sacramento is interesting because it can represent enormous forces of change, not just the forces of change within the community, which is certainly true – to the state and to the nation – enormous changes that it represents. And it’s like having a locomotive on a pedestal without explaining what it means. PRINCE: Yeah, what its significance was. Not just for the immediate surrounding community, but for the wider community in this case – not just for the city of Sacramento, or the state of California, but for the nation, and for the world … HENLEY: That’s right. Exactly. PRINCE: … when you think about what happened in that little place. I know there’s – like you say, the heritage history, or the celebratory history, the discovery of gold – but when you really study that and you think about what happened in that short period of time – how the world sort of converged on the banks of that river there and moved out from that point – that has so many stories to tell, and I think that that would be one of the real important parts of significant history that is missing there. HENLEY: Well, you know when you talk about Old Sacramento; just about everybody knows who the big four are. Certainly a large number of people know about John Sutter Jr., and the founding of the city, or they know about Sam Brannan, or they know about early governors that were down there, or maybe D.O. Mills and his banking empire, things like that. But, you know, almost no body knows about the people that came and worked there every day, and almost nobody knows about what the impact was of these events that occur – be it a major advancement in commerce such as banking represented in California, or the railroad – that’s the thing, nobody knows about what that means to the people that were here. Or for that matter, beyond here, and that’s the unfulfilled promise. Ultimately, I think that’s what will either make this project continue to be a relatively highly significant historic district nationally, or it will shrink into something less and less important and perhaps ultimately its historic value will get lost. PRINCE: Or just serve the tourist objective. HENLEY: Ultimately just serving a tourist objective. It could be the difference between history that is well documented, and perpetuation of a myth. PRINCE: Right, right. And I guess how creative the interpretation of that documentation can be. HENLEY: But you know, the importance of the bones is hard to ignore. I remember being involved and actually being quoted in an editorial in the Sacramento Union many years ago about the B. F. Hastings building. The state was looking at the B. F. Hastings building and was somewhat appalled by the challenges of its physical deterioration, about how they would restore it and preserve it. And there were people in the state architect’s office who were advocating we just tear it down and reconstruct it. And an editor at the Union called me and asked me how I felt and I sort of cavalierly said, “Well you know some people will go a long ways to see the real thing, but won’t go around the block to see a replica.” And I think that’s sort of what the bones represent down there, and I think that for some people a story well told about things that are happening in Old Sacramento are more meaningful if you’re standing there and looking at the building where it actually happens … PRINCE: With the actual bones … HENLEY: … than not. Yeah, if you tell it in the classroom it’s a different environment. PRINCE: Absolutely. That kind of goes back to Aubrey Neasham’s idea of arrested decay, or I had read a statement of his that he had given – I think it was before the Legislature in one of these articles I read about the freeway battle – where he had said that he thought it was, the best thing to do would be to rehab something, that to reconstruct was the worse case scenario. I mean if that was your only option left available, you would take it, which is I think what happened to some of those, the big four and such, but he always, like you had mentioned earlier, believed that authenticity was most important in preservation. Because he felt –there was also a project he’d been working on, I can’t remember the name of the mission, it was a mission, and it was, parts of it were in ruins and he had said that he thought it should be kept in that state. That was more significant than if you just rebuilt something and if you didn’t have enough evidence to show you exactly how it should be then you were really corrupting the authenticity of its history. HENLEY: He comes up out of a period when those kinds of ideas are actually pretty revolutionary. It’s only fifty, sixty, fifty years before Aubrey is an important figure in history circles that you have fundamental issues being resolved about Sutter’s Fort. Where you have a group of people who kind of know history was made there, they know it’s important and they go out and look at it and they try to figure out what to do and the immediate reaction is, “Well, there’s this crummy little adobe building left, if we just tore it down and built in its place a monument, we can tell the whole world what happened here.” [End of Tape 4, Side A] [Begin Tape 4, Side B] PRINCE: 1895, or something like that? HENLEY: Yeah, 1889, maybe, as early as 1888, ‘89. And you know, people start to think about it and say, “Oh we need to save this remnant of this building, maybe we should reconstruct what’s missing.” You know, it’s only fifty years later or so that he’s getting involved in and refining the idea, many of the ideas that we have in preservation today of should we preserve the evolution of things? Well, certainly in same cases he didn’t do that, but you can see he’s thinking about it you can see he’s trying to move a thought in a certain direction. He’s a very deliberative sort of thinker. When I first went to work I sort of asked him, “What do you want me to do for you, I mean what is it really that you’re asking me to do?” And it took a little while to get that out of him but finally what he said is, “I want you to be my devil’s advocate, I want you to tell me what you think is wrong with what I’m saying.” So I played that role for several years with him. And it’s interesting because in all honesty, he wanted you to be the devil’s advocate until he got angry, and then you knew to stop. You knew to stop at that point because it wasn’t going anywhere. Once he got angry it was the end of the conversation. But we used to sit there at a desk and just talk and challenge thoughts, and he would listen to that, and sometimes change his mind about how he did things. PRINCE: Now was this concerning details of buildings, or people that had lived in them, and things that had occurred? HENLEY: Well, it certainly had to do with restoration and reconstruction and preservation and where each of those topics belonged in a hierarchy. PRINCE: For this project? HENLEY: For this project. But frequently would range to much more philosophical attitudes towards preservation or the writing of history. He and I did a publication or two together, and I remember the City of the Plains book that we did. I think we went through – they’re not very long chapters, the text is very short – I think we went through something like thirty-two or thirty-three drafts of this text. PRINCE: Wow. Discussing them together? Finessing it? HENLEY: Arguing what it meant, you know? And it isn’t all that important – the text in my mind now – but it was then, it was important to us at the time. And then I didn’t write it at all he wrote a thing called A Reference Point in Time, actually before I came to work and then we reissued it and cleaned it up and had it, in the graphics, improved quite a bit – put color in it and various things – and he agonized over that. He was a plodding sort of writer. He’d do these things over and over and over and over. PRINCE: Well just looking through his papers, some of his notes, you know, you look at them and there are a lot of places where he has lines scratched out and words above it, and then those scratched out, and I mean they look like a mess until you really study them and see what was going on in his mind as he was working on these drafts. It’s very interesting. HENLEY: Yeah. Well, he also had a luxury that historians don’t have any more very often. First of all, all of his adult life he worked for government and he always had a secretary. And so he was just used to getting draft after draft, and working it over and sending it back to be redone. I know people complain bitterly about my handwriting, but his was small. PRINCE: Yes. Very small. HENLEY: He crammed four or five – in a line on a tablet he put four or five lines of text. PRINCE: [Laughs] I’ve seen that in his notes. HENLEY: And he used ink pens that weren’t always good quality ink pens so they would skip, and he didn’t care if it was red ink or what and it would get to be kind of a mess. PRINCE: So now, we’ve talked a little bit about the cooperative efforts among the different interests in the project – the Sacramento Redevelopment Agency; by this time the state that had the State Park there, the historic State Park; your group who you were working with; so DeMars and Wells was through the Redevelopment Agency and you had a good relationship with them you say, that was a delightful experience … HENLEY: Very much so. PRINCE: … you felt that you were progressing very well with them, so I wanted to ask you about some of the other groups or interests, what were those relationships like? Did you come upon any obstacles, working with, say the city or the Redevelopment Agency, did they want, did they have different goals or did you feel like there was one common goal and was that articulated or how did that work out? HENLEY: Well, in the early 60s my perception was that the city had – essentially once the fundamental plan was adopted of having a historic district and having these various redevelopment project areas created – abdicated to the Agency to get it done. And even though I know, and I know more now than I did at the time, I know that the Planning Director, later to be City Manager definitely put a heavy hand on the Agency and how they would do things. I was not aware of that particularly at the time. I found that almost everything was defering to the Agency – we worked with the Agency. We actually didn’t work with city staff very much, I have to admit probably the first three years or so I didn’t know what the structure of the city was at all because my contact was so minimal. I knew somebody sent a paycheck, and I probably remembered who signed the check but that’s about it. The contact was with the Agency. PRINCE: So you worked with Ed Astone, the Project Director, quite a bit? HENLEY: I worked with Ed, quite a bit. I worked with a guy named Don Kline who was the Deputy Director and I don’t know what else they called him at the Agency. PRINCE: Was he the planner, the chief planner? HENLEY: He was the chief, sort of the chief planner, yeah. And then the first agency architect was a guy named Wes Witt that I worked with. PRINCE: Wes Witt? HENLEY: Wesley Witt. PRINCE: Okay. Was Clyde Trudell there when you were there? HENLEY: Clyde was there but he was going. He was going or gone by the time I arrived, and there was very little contact there because I think there was a lot of tension between him and Aubrey. Aubrey had no real respect for him. PRINCE: Oh. Was Clyde Trudell – he was an architect? HENLEY: I believe he was an architect who thought of himself as an historian. PRINCE: Well, yeah. Because I’ve looked at some of their correspondence – or correspondence of Clyde Trudell’s and he seemed, well he seemed like he was VERY specific about details about some of the buildings. I remember looking at some of his letters where he was questioning some decisions that had been made about – little details – about, say, you know, a doorway or the edge of this building or something like that. HENLEY: Well, the devil is in the details and in preservation, it really is in the details because the overall picture can look swell, works for ninety percent of the people one hundred percent of the time maybe, but ten percent – it’s what’s in front of their nose that they look at. It’s not looking at the whole building and if that doesn’t look right, they begin to question everything about it. PRINCE: So that brings me to another question. Was there ever a review process, an official review board appointed or selected from some of these different groups, to review the different developer’s blueprints or building plans to okay them? How did that work out, how was it enforced? HENLEY: Well, we were – it gets a little gray after the early 1970s. First developers start to come online, we’re still working for the Agency, we’re still essentially getting our money via the Agency to the city then to us. But the city is starting to have a little more say in what’s going on, building permits are being issued and Redevelopment can’t do that – the city has to issue the building permit. So when a proposal came through – I know your question was there a board or commission or somebody that looked at it – the Commission, the Museum and History Commission, or the old Historic Landmarks Commission, whichever it was at the time – actually had a review process, they could look at them but to be honest, they didn’t. They deferred to the staff to do that. That was us. Which means we were the ones that pretty much called the shots. First as the Agency’s consultant and then later on behalf of the city when we reviewed it, we were the same people doing the review. Some people might criticize that but it did expedite the process. PRINCE: So now, you just said something – the old Historic Landmark Commission, was that what merged into the History and Science Division? HENLEY: The evolution of the Commission is it started out as a historic landmark commission then it got reorganized and it became known as the Museum and History Commission, and when it became a Museum and History Commission it was a joint city/county commission rather than just a city commission. And then it morphed one more time and the Museum and History Commission got renamed History and Science Commission, or Sacramento Commission of History and Science. And it’s still a city/county commission and it still exists, but there was – when I went to work, there was a commission budget and we were part of that budget as staff. PRINCE: And this is that commission that began in 1953. HENLEY: That’s right the Historic Landmarks Commission. And after about two years the separation of powers business between the city manager and the council started to become an issue. I doubt it was really over us but we certainly got into it. And what it was is the charter says that the council doesn’t supervise employees and therefore their commissions can’t supervise employee. So it has to be city manager and budgets are prepared by the city manager and submitted to the council – that’s the way it is, you know, and somebody went back and explained that to the powers that be at the time and they realized they had to make some changes. So what happened is the Commission no longer at that point had a budget they became a Museum and History Division, well actually it was a department, the Museum and History Department. We didn’t become a Division – which was a reduction in our position … PRINCE: From being a department? HENLEY: From being a department until we got placed underneath the Parks Department. PRINCE: Was this in the seventies, or later? HENLEY: Yeah, it was in the mid seventies. PRINCE: So you were placed under the Parks Department? HENLEY: Yeah, which had another name at that time. It was Parks, and a bunch of other things. And so the Parks Department was a department so we had to become a division. PRINCE: Okay, you were a division of that department. And that was the way the hierarchy … HENLEY: Yeah, and before that when Rathfon was the city manager and the Assistant City Manager was Walter Slipe and Tom Ebner. Rathfon retired, Slipe became the city manager and he brought in, and Ebner was still there until he left, he brought in a guy named Bill Edgar as the Assistant City Manager and at that point we were still a department and the city had -- there’s a policy the managers met every two weeks as a group – but as a department we had essentially nothing to say compared to the fire department or police department, or the water department or the engineering department. So very quickly it was determined that they needed to have two department head meetings – big departments and little departments. And very quickly the manager didn’t have any time for the little departments to meet with them; he could only meet with the big departments. And so we were meeting with Bill Edgar who was the Assistant City Manager and then the head of Parks, at that time a guy named Doc Wisham, Solon Wisham became an assistant city manager. He ended up meeting with the little departments, you know, we were getting pushed down the pecking order pretty quick. There was about four of us that were called little departments. And then pretty soon they eliminated that. PRINCE: They eliminated the department and made you a division. And did you meet with any assistant city managers? HENLEY: Well, not officially at that point. We were meeting with the department head. But by then I had already become a little bit of a fixture around and so I always maintained some relationship with the assistant city managers or the manager. PRINCE: And this was in the mid seventies? HENLEY: Yeah. PRINCE: Okay. So back to the review process, that basically then was the responsibility of you and who else was working with you at that point? HENLEY: Well, at one point Neasham was involved for a little while but he left pretty quick and he wasn’t involved too much in that. It really was myself, and then I hired a fellow to really do a lot of technical research for me and he did a lot of the plan review, named Steven Helmich. PRINCE: Okay. So you guys reviewed – say a developer had bought a parcel, had accepted the requirements, the guidelines, had their little package there – what was supposed to be built at this site. Then they had their planners draw up some plans and then you guys would look those over and either okay them or not? HENLEY: Yeah, and there was some dissent that arose in the seventies about, you know, “Well, isn’t there any appeal beyond this?” sort of thing. And the city and the Agency agreed to establish an entity called the Old Sacramento Variance Appeal Board, and it was to be staffed by Agency staff and it consisted of a member of the Redevelopment Agency Board, a member of the Museum and History Board, and a couple, three people of specific disciplines, I think a historical architect and I don’t know what else, I can’t remember the exact makeup. PRINCE: And by this time – you’re a member of the Museum and History board? Not yet? HENLEY: I’m never a member of the board, never a commissioner. No, I mean the closest I ever got at one point I was their Executive Director, which was a title that the city, that I never felt entirely comfortable with, so they called me a division head later. PRINCE: I guess I’m trying to establish your history with the Division that coincided with the work you were doing for what was now the Museum and History Division, had been the Landmarks Commission, working with the plans and all of this – and then the plans for the Museum and History Center, was that happening at the same time? HENLEY: Yeah. Yeah it was. Old Sacramento gained virtually a hundred percent of our attention for about four or five years. PRINCE: And that was? HENLEY: ‘66 to ‘71, ‘72, somewhere in there. And we had gotten past building the Morse building, we had gotten passed the state starting the Big Four building, started in ‘69 and finished it in ‘70 or ‘71. And we had got the first buildings – private buildings under development contracts, the very first buildings were starting to go. And so it seemed like it was on a path and then we turned our attention back to the museum because that was one of the original focuses of the Commission, always had been to run and operate a museum, specifically a museum for Old Sacramento was in the package. PRINCE: And that was part of the State Park land, wasn’t it? HENLEY: Well, where we are now was at one point part of State Park property, yes. PRINCE: It’s not now? HENLEY: Oh no. The city owns the property now. PRINCE: Oh, the city owns it, I didn’t know that. HENLEY: Yeah, the whole relationship is kind of complicated down there. The streets, like Front Street and I Street within the State Park, well the city always owned that and when they created the State Park, I don’t want to say funky, but I don’t know any other way to put it, kind of an agreement came about where title transferred, I believe transferred to the state, but the city retained an easement right for the maintenance of the utilities, the addition of the utilities as a street they still have the right to utilize it but the Parks Department is responsible for the surface and … it’s a very strange, complicated relationship. PRINCE: So the Parks Department – you mean the State Parks is responsible for the maintenance but the city can use it? HENLEY: Well, and they preserve it as an easement. It’s a preserved easement and the city has the right to do anything. PRINCE: But the state pays for that preservation as an easement. HENLEY: The state pays for the maintaining as it is on the surface now. PRINCE: So now, is this the same Museum plan from long ago at Pioneer Hall when you were working with Aubrey Neasham to create a county and city museum or was this something different? HENLEY: Well, before my time the Commission had come up with a plan that said the museum should be in the Booth Building on Front Street and they even had drawings of it – some pretty primitive sketches of what it was supposed to look like. That quickly was determined not to be realistic and there was a study done, right about the time I came about where – they’d already decided they ought to do it in the Waterworks building but they thought due diligence that they should look to see if there were other sites that made sense, because it in fact was identified at the time that the building wasn’t big enough. PRINCE: The Waterworks building. HENLEY: Yeah. That it was not a big enough building to achieve any of the programming as a community museum, that it simply wasn’t big enough. And so we looked at a number of other sites at the time. We looked at the County Courthouse, which had not yet been torn down, that would have been an excellent site but the county just turned us off. PRINCE: And where was that located? HENLEY: It’s where the jail is now, on I Street. PRINCE: Oh, okay. HENLEY: It’s on that block, between Sixth and Seventh, on I, on the north side of the street. The county said, it’s a code deficient space to be in. Actually it was an excellent building. It would have been a stunner for the purposes, but it was taken off the table. Then the SPD [Southern Pacific Depot] was looked at as a site, and the general consensus at the time was it might not happen in our lifetime because the railroad wasn’t willing to let go of it. PRINCE: That would have been a good one too. HENLEY: It would have been a good one too. At any rate, there probably were a couple other sites to look at I don’t remember them now. Any rate, then they started to look at the Waterworks site and say, “Oh. Well what can we do on that site to make it work?” And we were sort of challenged at one point to say, “How much can you put into that site?” PRINCE: You mean in terms of the size of the building? HENLEY: Yeah, how much can you actually put in there and what version of the building do you want to build? Well clearly the aesthetically interesting building is the original building. After that they start to hack it up and change it, and it gets to be a pretty ugly looking building, but it does get to be eventually about four stories tall. So at one point we actually proposed the four story ugly building and that’s exactly the reaction – too ugly! PRINCE: And what time frame would that have been? [historical] HENLEY: 1870S, ‘80s. So we went back and looked at the original building and all we could do is bump out in the back of it about fifteen feet, which is not part of the original building but it’s the building has got three sides and it turns and then there’s a boxed out projection in the back of it that goes back towards the Railroad Museum. PRINCE: Does that go up the three stories? HENLEY: It goes up the full height of the building. And that gave us space for things like fire exits and elevators and some restrooms and things you got out of the basic core of the building so we could use all the space. But as it was we couldn’t come up with very much square footage, so from the beginning the challenge was no one wanted to tell less of a story, everybody wanted to tell a big story, and so it became how much stuff can you put in this little box? And so the end product of the museum when it opened was a density of artifacts that was sort of overwhelming – there was so much stuff in a little space. And even at that we were forced to do something that wasn’t even imagined at the time – telling part of the story was telling about the community and the communities – the cultural and ethnic groups that show up here. And their story alone was as big as the whole museum had physical space for – forget all the other stories. PRINCE: Was this the ethnic survey? HENLEY: Yeah. And so we started looking for an imaginative way to do that and we came up with placing it throughout the community gallery as computer terminals with touch sensitive screens and we could pack a lot of information into these computers that take very little floor space and it was kind of a first. I mean, it isn’t the first interactive exhibit by any means in the museum but it was a real interesting issue. We had something like twenty monitors total when we were full blow. And I remember it well, because the original programming, the research for this was NEH grants. PRINCE: Oh, it was? HENLEY: And they were big NEH grants for us, really big – I think the two grants for the ethnic study might have totaled maybe close to three hundred thousand dollars. PRINCE: And when was this done? HENLEY: It was done two years before the museum opened, I’m a little confused now about when the museum opened, but I think it must have been around 1985. [End of Tape 4, Side B]