[Session 1, July 18, 2007] [Begin Tape 1, Side A] PRINCE:

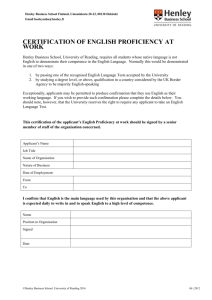

advertisement

![[Session 1, July 18, 2007] [Begin Tape 1, Side A] PRINCE:](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/017530535_1-bc421d99cd5f08b6bbc71f3c652e2465-768x994.png)

[Session 1, July 18, 2007] [Begin Tape 1, Side A] PRINCE: Hello, my name is Lisa Prince, and today is Wednesday, July 18, 2007. I’m here at the Sacramento Archives and Museum Collection Center in Sacramento, California, on behalf of the City of Sacramento’s Historical [Old] Sacramento Oral History Project. Today I’ll be talking with Jim Henley, the manager of the Sacramento Archives for our first interview. Good morning, Jim. HENLEY: Good morning, Lisa PRINCE: How are you today? HENLEY: It’s an exciting day – let’s just get on with it. PRINCE: Okay. Tell me when and where you were born. HENLEY: I was born on June 14, 1944, in Sacramento, California. PRINCE: Oh, you were born in Sacramento. HENLEY: Didn’t grow up here, but I was born here, yes. PRINCE: Okay, and where did you grow up? HENLEY: Mostly south in the valley, east of Modesto, a little town called Oakdale. PRINCE: Oakdale. What was that like growing up there? HENLEY: A little farm town. PRINCE: A farm town, did you live on a farm? HENLEY: I did live on a farm, yes. PRINCE: And what did you farm there? HENLEY: We had nut crops, walnuts and almonds, and my grandfather, who owned the place originally was a chicken farmer. PRINCE: Oh, so there were chickens there too. HENLEY: Way too many chickens. PRINCE: Way too many … how do you feel about chickens today? HENLEY: Well I like to eat them only because it does them more harm than me. [Laughter] PRINCE: You hope … HENLEY: I was not very fond of being around chickens. PRINCE: So, what were some of your childhood interests, hobbies, or things that fascinated you while you were growing up in Oakdale? HENLEY: Well, I think probably the answer to that lies in the fact that we were in a rural setting, there were no children my own age anywhere nearby, and it was a pretty good hike to anybody’s place. So, it really was – and my brothers, I have two older brothers, they’re six and eleven years older than I am. PRINCE: Oh, what are their names? HENLEY: Well, the middle brother’s name is Bill, or William, and the older brother is Ronald. And so consequently it’s sort of a self-contained childhood for a large measure and you know, the family is fairly literate certainly. My mother was a teacher and my father was an engineer. We were encouraged to read a lot as children. I read extensively and I kind of lost myself in books at a fairly early age. PRINCE: What did your mother teach? HENLEY: She started out in a one-room school. PRINCE: In Oakdale? HENLEY: No, actually, about thirty miles from there. It was her parents’ farm that we moved to – and then eventually, she settled on fourth grade. PRINCE: Okay. So what kinds of stories were you interested in when you were reading as a child? Was it just all sorts of things, or were there particular types of books that you liked more than others? HENLEY: [Laughs] Actually it’s fairly, pretty universal what I would read. I did take as a child quite a bit to world geography, I loved science books, I loved travel log kinds of books. I also have, always have had a long fascination with literature and particularly mystery, science fiction, but I was reading classics at a pretty early age. PRINCE: So, that brings me to my next question concerning your education – did you go to a one-room school when you were a child? HENLEY: No, no. Interestingly enough Oakdale had a – Oakdale was not a small school district – they were one of those we used to call union schools. They moved all – long before I was born – they moved all these little school districts into one. So the grammar school districts – some of the kids traveled an hour and a half or two hours on the bus to get to the schools. And we had big schools – in the school district I was in there was probably four, maybe five schools in a town that was only ten thousand at most, or probably less than that when I was a child, maybe five-thousand when I was a child. The high school had a -- the high school graduating class was about a thousand – so it’s a pretty good-sized school. PRINCE: That is a good-sized school. HENLEY: A good-sized school. PRINCE: So were you one of the children who had to travel for hours on a bus in the early days? HENLEY: No. My travel time on the bus was relatively short, relative to others. I probably had a twenty-minute ride. PRINCE: Oh, that’s not bad. So now, when did you come back to Sacramento? HENLEY: Well, after high school I spent a semester, maybe it was year – I guess it was a year, in junior college. I had done some extension class work through the University of California, actually when I still in high school, then I spent a year in junior college – that’s in spite of the fact of having a scholarship to go to Santa Clara, which I didn’t want to … PRINCE: Why not? HENLEY: Actually, well, I had a girl who I was interested in, and she wasn’t there, that’s why I went to junior college. PRINCE: Oh, I see … HENLEY: Then, that scholarship was gone, the opportunity was gone. My father’s mother, my grandmother wanted me to go the Stanford – she was, as I understand it, the first woman to graduate from Stanford University. PRINCE: Oh, what was her name? HENLEY: Stella Henley. PRINCE: Stella Henley. When did she graduate from Stanford? HENLEY: Well, it was right around the turn of the century, thereabouts, I don’t know exactly the year now without looking into it. At any rate, she always had a long time relationship with the university and she was willing to pay for the room, board, and tuition and the whole thing if I would go. And it was a dumb move, I should have done that, but I didn’t. PRINCE: So you went to junior college, where was that? HENLEY: In Modesto. Now it’s called Yosemite Junior College, but it was Modesto Junior College. Then I did a summer school session at Cal, and then I’m still chasing a girlfriend … PRINCE: Same girl? HENLEY: Yes, same girl. CSUS – that’s where I went after that and then I finished there and then I went into graduate school there. PRINCE: So now, what year was this when you went to CSUS – do you remember, approximately? HENLEY: 1963, I believe. PRINCE: And what were you studying there, Jim? HENLEY: Ahh, that’s a good … I took history and anthropology, and I actually ended up with enough units to have a degree in either one, but they wouldn’t let us do that. PRINCE: They wouldn’t? HENLEY: They wouldn’t let us do that at the time. PRINCE: You couldn’t do a double major? HENLEY: You had to have a major and a minor, and then you could have another major but it couldn’t be your minor – at least that’s the way it was explained to me. I actually kind of wanted to get a degree in archeology and a degree in history, but I had to pick one and I took the history. PRINCE: History. So it was archeology, or anthropology? HENLEY: Archeology was within the anthropology. PRINCE: I see. Did you find that that was helpful when you started some of the projects in Old Sacramento? HENLEY: Oh, it gave me a definite bent towards that. PRINCE: It’s definitely a good mix. HENLEY: Yeah, it was helpful, it was not the cause for my getting a job in Old Sacramento by any means, but it was helpful when I had the job and certainly in later years it was very helpful because I managed a number of archeological digs, I supervised contracts with archeologists. PRINCE: Was that in Sacramento, Old Sacramento? HENLEY: Yes. PRINCE: So – I’m going to go back just a little bit. When you came back to Sacramento – that was after you did your summer at Cal, and then you came back to CSUS, so you moved here by yourself, you weren’t with your family, did your family move back to Sacramento? HENLEY: Oh no, no. No they stayed in Oakdale. PRINCE: What was you impression of Sacramento then, what was it like in the early sixties? HENLEY: Well, you know it wasn’t like it was coming back to a place that I didn’t know because as a child, we would come back every once in a while, and so there were certain things that I had familiarity with, so it was a familiar place to come back to. [phone rings] The whole adventure of coming back here – I didn’t have much of a feeling for the town because I moved into the dormitories of the college and it was isolated, it was sort of – there was Sac State and then there was the rest of the world. I mean, where did you go if you didn’t have a car at the time, about as far as you went was Shakey’s, you know, or you went to the river, that was about as far away from the campus as you went. It was probably in my second year there when I got a car that I started really getting around town and seeing a lot of the areas. Sacramento was an interesting town in the 1960s. There still was a downtown, though not as it was maybe in the fifties, but there still was a downtown, people still shopping downtown, most of the department stores had some presence downtown and it was kind of an exciting place to go do that. There were a couple of fairly substantial shopping centers that had come up – the ones out in the north area like, at El Camino and Watt Avenue. They were a little further than I would have normally traveled to so I didn’t really know much about them, on the other hand, I did get as far as Town and Country – which I went to quite a few times. PRINCE: Wasn’t that the first shopping center in the … HENLEY: Recorded as being the first one, along with Southgate, yeah. And it was pretty exciting, I kind of liked the place because it was full of interesting old stuff. PRINCE: Artifacts? HENLEY: Yeah, artifacts. And I later found out a lot about how that stuff came to be but I didn’t know then. It just looked like it was an interesting place and they had interesting shops and so we’d get out there. And then gravitate downtown. Downtown was still where for us students it was where the action was. I can remember when I was a senior, there were a lot of students living in the dormitory who, you know, had kind of challenges – they were of drinking age and so how could they drink their way through town in bars going from A to Z. PRINCE: Oh? Were there a lot of bars? HENLEY: Oh, there were a lot of bars. PRINCE: From A to Z, huh? HENLEY: All the way to the Zebra Club, yeah [Laughter] PRINCE: So, did this … I guess downtown, was it larger than it is today – I mean in terms of what’s considered downtown – for shopping, or theaters, or restaurants, or would you say it’s bigger now, within that old city grid? HENLEY: Oh, the commercial area is bigger now than it was then, but the activity was more compact along J Street and K Street, and not as vertical as we see the streets now with the high-rise buildings – there were three or four buildings of significant height, you know, maybe five. There was the cathedral, which still loomed pretty high, and the capital that showed up and the Elks building and the 926 J building, and then you’d go down towards the waterfront, there would be the California Fruit building which stood up fairly high. Those were the tall buildings and everything else fell below that. And people who worked downtown, shopped downtown, and you could see it at lunchtime, they would move out at five o clock they would move out into K Street and shop, before they went home. PRINCE: So, when you say that they shopped, was there, for example, what was the department store? HENLEY: Weinstocks and Breuners were the two big ones but there were a number of them – there was the Roos Atkins, there was the … PRINCE: Woolworth’s? HENLEY: Woolworth’s was down there, Kress was down there, Sears was down there until they moved out eventually, which was actually just a little before my time. PRINCE: Were there also things like bakeries or little markets, and fish markets, or those sorts of things that people … HENLEY: I don’t remember too much of bakeries and I don’t remember a fish market downtown, but there was a big fish market on Ninth Street, Ninth or Tenth, and T or U, called Capital Fish Market. But I don’t … there were a lot restaurants downtown, seriously congregated right around K Street – not like we know restaurants today – Sacramento’s loaded with restaurants today, there’s a restaurant at every corner, but there were a few old mainstay restaurants downtown that you certainly went to, you know, the furthest out you probably went was Rosemont, on Folsom Boulevard just above Alhambra. PRINCE: Now is that gone? HENLEY: The building is still there. That became, I think, Andiamo’s. PRINCE: Okay, I think that’s changing hands again. HENLEY: I believe it’s closed right at the moment. PRINCE: So it sounds like there was more of a lively type of community there in Old Town, where, I mean in downtown, whereas I think after the urban renewal projects with all the state buildings going in and all of the clearing, it’s really changed that type of culture of downtown. HENLEY: Yeah. When I started to go downtown, redevelopment was already starting to have really significant impacts. PRINCE: I wanted to ask you about that. HENLEY: They were beginning to clear a lot of spaces, and yes, one of the first things to disappear was the residential component of downtown. And it would be easy to say that redevelopment displaced low income or unemployed people out of the West End, but they would displace more than that. There were actually a lot of apartments that were – I wouldn’t call upscale by our standards today, but they were certainly upper working class and lower middle class apartments and they went. PRINCE: Were these in the West End or were these just sort of scattered in the … HENLEY: Well, they went up as far as Twenty-first Street, but certainly the most famous of that group was the Merriam Apartments that was torn down for the Convention Center. PRINCE: Which we have some of here in the archives. HENLEY: We have one apartment here, dismantled, yes. PRINCE: So some of the large-scale clearing was happening when you came here at this time, and you could see that. What did you think of that when you first started noticing it? HENLEY: Well, the initial reaction was kind of exciting, ‘wow, look at this they’re clearing and going like crazy’ but, you know, then I came to work down here and as I watched year in and year out, the lots stayed empty lots. And the only revenue they were generating was as surface parking – I parked in many of those lots when I worked, several of them, and they were cheap enough – the redevelopment gave almost free parking, of course you had to worry about nails in your tires and things like that because you literally were parking on the rubble of buildings that they demolished. PRINCE: Had torn down. So, now, did this happen quite a bit in those days? I mean did they have plans for redeveloping some of these places that they had torn down like the Merriam Apartments, and then those deals fell through – why did that, why were those lots empty for so long? HENLEY: Well, before I was involved with the agency, or through the city, or any of those things, it was clear the agency had adopted some master plans for redevelopment. They didn’t tear buildings down before they had a concept of what they wanted to do, but they may not have had a specific plan. And a case in point – you could see the clearing was significantly related to Capitol Mall first, and then over towards L and then K Street, and then over to J Street. And it was between roughly Second or Third Street up to Seventh Street – was the most seriously impacted – eventually they would go on up K Street and work around where the Convention Center is to clear space for that. I don’t know that until fairly recently redevelopment went above Fifteenth Street, I think they stayed mostly below Fifteenth Street, if not entirely until fairly recently. The earliest projects were along Capitol Mall, which was M Street – got renamed Capitol Mall to make it a little more attractive. The problem seemed to be that the conceptual plan drove the agenda to clear the blocks and then once they cleared the blocks, then it was a question of a specific plan, and adopting that specific plan with a developer, and then became the game of jockeying the government agencies – being the city or redevelopment – and the developer over what each was going to do, and as far as lower K Street was concerned, they went through a whole succession of developers and plans emerged, and then the deal could never be consummated and so then the plan would disappear. I used to watch those kinds of plans come and go and I came to develop a sort of cynical term for it and I was always eager to collect those plans and keep them because I considered them almost history, they never really happened – they were dreams but never really happened. PRINCE: Were there actual blueprints or renderings? HENLEY: Oh in many cases there were blueprints, but there were renderings, certainly renderings. Blueprints, maybe lots of them never got to the point of actually doing architectural drawings for the buildings. PRINCE: I see. HENLEY: And they worked with very large companies that were taking advantage of redevelopment activities all across the country at that time, and there were major companies – one of them was an outfit out of Los Angeles called Kishman, another one was Reynolds – the Reynolds aluminum people – some huge plans – later it would be Rockefellers, and there were plans for building with them. But it always seemed to get back to what is reality versus what is the dream and the city became so concerned about the – called the ‘bombed out look’ – in downtown, that they started to say, “Wait a minute, maybe we need to work with some local people and get something done.” PRINCE: Because they would have more interest in seeing something actually go through rather than … HENLEY: That’s right, and besides, they’re a little easier to get a hold of and shake their body and say, we need to get this done, you know, and vice-versa, they have a little more power on local government if you’re somebody local. And so there was a combination of families that got together, including Teicherts, who came in and said, “Listen, let’s put together a K Street downtown development and they ultimately worked with the agency and the city to build the multilevel, underground garage that goes from L Street to J Street, and from Seventh Street to Fifth Street, approximately, so that’s four square city blocks underground parking, virtually. And then they built a shopping center on top of it, which went from Seventh Street to Macy’s – at Fifth Street, Macy’s was a stand alone project. And in part, in conjunction with that the agency redid the K Street strip as a mall, a pedestrian mall from Seventh down to Fifth it was done as part of a shopping complex, but before that from Fifth Street to Third Street, or Fifth to Fourth, in front of Macy’s they hired a Los Angeles firm to do a mall design. And I want to say it was Victor Gruen, but I’m not sure that’s right. PRINCE: Now the city hired them to do the mall plans? HENLEY: The city and the Agency. PRINCE: And the Agency. [Redevelopment] HENLEY: And they put a very elegant one-block mall strip there with reflecting pools and concrete seating benches, and sort of large, concrete animals that kids could play on or ride, they were little sort of interesting little hippos, and snakes, and various things for children – very nice, fanciful sculpture, and it was a very attractive piece. The piece from Fifth Street to Seventh Street along with the mall was quite different, but again, it was reasonably tasteful. Then the city felt that the Convention Center and Seventh Street – the distance between that was blighting fast, there was nothing going on, so they decided a mall would revive it, they would build a new mall in there. The council decided on an engineering firm in, I think Kansas, to do the design, they weren’t an architectural firm, they were an engineering firm … PRINCE: Was this for the pedestrian mall that they were … HENLEY: For the pedestrian mall from Seventh Street to what’s now the Convention Center. And it was a major rip out of a traffic street, I mean there was serious impact on the city. And then as the mall began to emerge, the structures began to emerge, some people were appalled by what they were seeing, and the city got pretty negative about it in the community, in fact they frequently referred to the features as tank traps. PRINCE: What were they? HENLEY: Well, they were geometric, concrete shapes with waterfalls that came out of pipes and there was one at the – by the cathedral that was down there, and other than a few people that played in it occasionally, most of the time people referred to it as an overflowing storm drain, or sewer, or … it just didn’t appeal, it was very angular, very sharp. It was a lot of concrete. Teichert poured all the concrete and I can remember one of – a senior Teichert, Henry Teichert’s brother, Adolf. Adolf and I sat in a meeting and he said, “It’s so embarrassing. We poured that concrete. It’s so ugly, we’re so embarrassed.” And so they just really felt bad about it, and to show you, even the city council – some of them – realized that this was a huge mistake, a young councilman, who voted for it, who was gung ho for this development – a guy by the name of Ralph Scurfield – and I’d known Ralph for many, many years. PRINCE: He was a council member? HENLEY: He was a council member and a developer, a major developer in Old Sacramento, involved in lots of historical activities. Ralph and I sat in a meeting and he goes, “You know, we saw the plans and we didn’t realize what we were approving.” PRINCE: Why didn’t they realize it? HENLEY: Well, I just don’t think they could understand what it was they were seeing, they couldn’t visualize it as a three dimensional thing. PRINCE: I see, the drawing looked a lot better than real life … HENLEY: The drawing looked a lot better than real life, and he said, “You know, that’s one of the worst decisions I ever made, when I was on the council.” And I think he really believed that. It was one of the worst decisions he ever made. So it was, it started out with bad reviews and it never got better. PRINCE: And when was this put in? HENLEY: Late ‘60s. PRINCE: So how long did it stay there? HENLEY: It was torn out, I can’t say exactly, it was torn out, actually for light rail. PRINCE: In the eighties, maybe? HENLEY: Yeah, in the eighties. PRINCE: So it was there for about twenty years, how could people put up with it that long? [Laughter] HENLEY: Yeah it was pretty – and it received lots of criticism. Merchants continued [complained], their businesses started to close because no one could park in front of their stores. That was their excuse for why they were going out of business, because no one could park there. And it’s true, it became a backwater because there was no traffic going down the street, whether they were parking there or not, there was no traffic anymore. And the pedestrian traffic was pretty insignificant because usually people go down malls to go from one place to another, and that’s not what the mall did. It was just a mall that really wasn’t succeeding in attracting people to go from one place to another. And it was not easy … [End of Tape 1, Side A] [Begin Tape 1, Side B] PRINCE: So the mall was not … really as attractive as it was hoped to be. HENLEY: Yeah, I mean people just simply couldn’t get across it, I mean it was difficult to traverse from one side to the other. You had a path that didn’t take you where you wanted to go. You wanted to go from that store to that store but you had to go in a diagonal path out of your way to get across, to come back, and so it was pretty unsatisfactory. And then of course the architectural critics were pretty quick to point out it was done by engineers, after all it wasn’t done by a real architect. PRINCE: Oh, okay. So the engineers were the ones who delivered the drawings and everything to them and …they actually did that? Didn’t have a design crew do it, or? HENLEY: Well, the engineers had a design crew, I’m sure. I don’t know … never heard from the firm again – they’re in Kansas somewhere. PRINCE: Kansas. [Laughter] PRINCE: So, that was one of the early urban renewal projects. It seems that the very initial one was supposed to be, just maybe – I had read something about two blocks, or maybe four blocks in the – you know closest to the river, and then it was expanded to, I think, fifteen blocks, the Capital Mall project and the riverfront project – so there were several of these projects going on … HENLEY: The agency had gone through a number of project description changes from the 1950s to the time I showed up which was in late 1965. The, and I can’t give you an exact breakdown of the evolution of each of those other than a general knowledge of what happened. You’re right, they had a smaller project to begin with. The first project was really the Capital Mall project, and they would give that a number, I sort of vaguely remember it being called project 2-A, or something like that. Then I guess there was some significant reason, in terms of acquiring federal money for redevelopment, why you would either enlarge a project area, or create a new project area, so you have these issues where 2-A gets expanded to include, I believe the freeway right-of way, and Old Sacramento. But then they redefined them as project 4, and then they had a project 3, and I never did hear what project 1 was, I’m not sure there ever was a 1. [Laughter] PRINCE: I think 1 was the designation of the redevelopment area, which was the two blocks in the very, west, west end – skid row – is what it was called, and I wanted to ask you about that. What was your impression of that area, what was considered skid row, or the slums? HENLEY: Old Sacramento was pretty, a pretty tough area below Seventh Street. PRINCE: Back in there, below Seventh … HENLEY: And to be honest, it probably was below Fifth Street for the most part, that it was really kind of tough. The best example I can think of to illustrate how tough it really was down there is my own experiences, and you know this is 1965, this is not 1950s. In 1965, the first legitimate reason I had to be in Old Sacramento for a project, a job – was as a student at Sac State. I was given the opportunity to help save a building in Old Sacramento from being demolished in lieu of taking a midterm for a class. PRINCE: Oh, that sounds like a good deal. HENLEY: It was a very good deal. PRINCE: Now was this when you were, had you met Dr. Aubrey Neasham at this point? HENLEY: It was his class. That’s where I met him. PRINCE: Yeah, I wanted to hear about that … HENLEY: So I go down there and what’s the first thing I see when I get out of my car on a Saturday morning? There are two guys, not more than twenty-five feet away from me, going around in circle, one with a knife – fighting. PRINCE: And where was this? HENLEY: It was between Front and Second Street on J, at the alley. A big guy and a little guy. PRINCE: With a knife. HENLEY: The big guy had the knife. Little guy killed the big guy with a pipe. PRINCE: And you saw this happen? HENLEY: Right in front of my eyes. PRINCE: Oh my goodness … HENLEY: I wasn’t twenty-five feet away from them. That’s my introduction to Old Sacramento. On the other hand, I don’t consider the people who were living down there to be nearly as dangerous sometimes as the people who went into the area. As an employee of the city, the only time I was ever threatened down there was by bottle hunters or diggers who were down there to try and dig or somehow steal out of the area. I was never threatened, I was never, I never even felt threatened by the people who were living in the area. PRINCE: I see. So, were there any families living down there? Where there … I know there were a lot of seasonal laborers, and then of course … HENLEY: Well I know by the statistics that there were some families down there, but I honestly don’t have a memory of seeing a family unit down there. Mostly it was single men, but the ones that you probably remember are the women down there. Used to call them bag ladies because they frequently would wear plastic bags. PRINCE: They wore the plastic bags? HENLEY: They’d wear the plastic bags, because they’d provide warmth. PRINCE: Were they homeless, or did they live in … HENLEY: Of course they were homeless. There were a few who lived in what we would call flophouses in the West End. But sometimes they could afford a room and sometimes they couldn’t. There were people who were living under sidewalks, there were people who were living in the flophouses themselves on a night by night basis, there were a few people who lived long-term down there, who were working stiffs that were at the railroad yards or someplace like that. PRINCE: So there were houses? HENLEY: No, there weren’t houses, they were more like apartments, or hotels that were providing some services, and you know, it was all pretty substandard stuff by the way we look at it now, you know, it might be a hotel room with a hot plate that’s an apartment. PRINCE: Was it more like a warehouse district at that time, I mean if you were to go there now, would you have seen the warehouses along the river where now you have the docks? HENLEY: Well, Front Street had two rows of wooden warehouses that paralleled the river between the river there were two sets of warehouse structures, and there was a railroad track running between them. PRINCE: Now was this from J, or I Street? HENLEY: This would have been from I Street all the way down to O or P – sometimes it was only one row of warehouses, but in what we called Old Sacramento, there were two, one on each side of the tracks. They were owned by the Southern Pacific – they were in fact, the interchange between the railroad and Pacific Motor Trucking, which was a trucking company that Southern Pacific owned. The area was kind of interesting in that from Front Street up – the city Police Department was the responsible law enforcement agency, even though technically they should have been from Front Street to the River, they deferred Front Street to the River to the Southern Pacific Police Force. PRINCE: So the Southern Pacific had there own police force? HENLEY: They had their own police force actually authorized by the Legislature. PRINCE: Really? I didn’t know that. So these were more than just security guards there? HENLEY: Oh absolutely, absolutely. And you might find things happening like what I experienced between Front and Second Street, but you didn’t see that kind of problem between Front Street and the River, because the railroad – their police were tough. They were no nonsense tough people, and so transients and people tended to stay away, they’d move across the street into the older buildings between Front and Second before they would mess around with the SP Police – they were really hard-nosed tough, tough, tough. PRINCE: Did they have their own jail down there, or did they send people to the … HENLEY: No no, they used the city jail, if they went that far. PRINCE: Wow. HENLEY: They were heavy on the billy club, very heavy on the billy club. PRINCE: Did they ever … make people disappear? HENLEY: Oh I don’t know about that, I think they wanted them to appear – but to look rather bruised, as a warning to stay off the lines. PRINCE: So it was a pretty rough area in lots of regards as you say. It was also, from what I hear, one of the largest central hiring places for agriculture and the railroads, and … HENLEY: Yeah, even when I came in ’65 you could go down there at oh, 5:30 in the morning and there would be several hundred people waiting to get a job through one of the labor agencies, farmers would come in with trucks and pick up laborers by the truckload, or if they were a little more organized, by bus, but it didn’t usually end up that way. And there were a lot of those older buildings converted into actually what were called labor agencies. And you would go there as a farmer and say, “I need fifty farm laborers, or I need a carpenter, or I need a plumber, or whatever. And they would match them up with … (unintelligible). PRINCE: … were these some of the businesses that were designated blighted and … HENLEY: They were certainly ones that were moved out and I haven’t followed them after they moved out, I don’t know where they are, I’m sure there must still be labor agencies, something like that, but I haven’t followed it after they left the West End. PRINCE: Well, let’s get back to Dr. Aubrey Neasham, tell me about the circumstances of your meeting him, and what your relationship was like with him. HENLEY: Well, when I was in graduate school, one of the important things, of course, at that time was if you wanted to maintain a – your status as a graduate student you had to take the equivalent of six units, and I only had three going and I needed another class, and a guy I had known in the dormitories wanted to be a park ranger, and he said, “Well you know I’m in this new department they got up at college called Park Management, or maybe it was called Environmental Management, I can’t remember. And he said, “I’m taking this class from this guy who’s a historian named Aubrey Neasham,” – who happened to be the head of the department too – “He’s really interesting.” And he said, “he was the former National Park Service Historian for the Western Region.” And I thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” Because to me, the idea of teaching did not appeal to me and I didn’t know what I was going to do with a history degree but I knew I didn’t want to teach. So, I thought, “This class will be interesting, it won’t be too hard, obviously, I’m going to take this class.” And it was a class on Museum management. PRINCE: Museum management … HENLEY: So I went to this class and the whole purpose of the class that semester was to design a hypothetical museum, which wasn’t hypothetical at all. Neasham had cut a deal with the city to open up a temporary city-county museum in a building downtown called Pioneer Hall. PRINCE: On Seventh Street? HENLEY: On Seventh Street. And so we’re plowing through this course and designing it and Neasham wanted somebody do some drawings for this and drawings for a contractor to build some walls and things inside the building. And he asked for a volunteer, and said, “Anybody have any experience with that?” And I raised my hand because I had worked a little bit as a draftsman, and my father was an engineer so I knew a lot about surveying and drawing plans and stuff like that. So he gave me the assignment to draw this drawing of a floor plan for this exhibit. And I was enjoying it and then it was time for a midterm and he said, “Now, we just got a building that burned in Old Sacramento, and the city wants to tear it down, now if any of you want to volunteer to go out and save this building, you need to clean it up so that the Redevelopment Agency doesn’t board it up, to try to save it before it completely collapses. If you want to volunteer to do that, I’ll do that in lieu of a midterm. So that’s where the former story comes from. PRINCE: Ahh, I see. HENLEY: Then the end of the semester was approaching and he said, “We’re going to build this museum now.” PRINCE: In that building? HENLEY: In that building. PRINCE: Now it hadn’t completely burned down obviously … HENLEY: Oh, no, no, no – a different building, not the building that burned, the building on Seventh Street. The building that I’m talking about that burned was on – between Front and Second on J, which was where this incident happened with the pipe. It was nothing to do with the museum, he just wanted to board up a building and save it, and he offered us an opportunity in lieu of a midterm exam – we jumped on it. It was a pretty big group of guys. [Laughter] PRINCE: Was it? HENLEY: Yeah. PRINCE: So there were several of you in the class that decided to do the project? HENLEY: I think there were probably about fifteen of us in the class, and I would bet at least fourteen of the fifteen thought it was a good idea. PRINCE: Okay, just to be clear – this was a building on you say Front and … HENLEY: On Second, no, it’s on J Street, between Front and Second – it’s called the Vernon Brannan Building. PRINCE: Oh, okay – so that was the building that he wanted to save. HENLEY: Yeah. PRINCE: Okay, and the Sacramento Redevelopment Agency was going to demolish it? Was that part of their plan? HENLEY: The city building inspections condemned it because it had burned and so you have to demolish it – the agency already owned it. They had acquired it and vacated it. It burned because a group of transients had gotten into the building, and it happened in a lot of buildings down there, when it got cold, they’d tend to scrape up some pieces of wood right out of the floor into a pile and start a little fire … PRINCE: In the building? HENLEY: Right in the floor of the building, and they put it out, theoretically before anything collapsed or burned down, but they’d do that to keep warm, and sometimes it got away from them, or they got drunk, or this and that, or whatever. PRINCE: And this time it did … HENLEY: And it did, it got away from them. Or they thought they had put it out and left, and it still had a glowing ember, and it fanned itself up and turned into a real big fire, burned out a piece of the floor and the support structure on one side and a wall fell into the alley, that was an exterior wall of the building. That’s how that happened. PRINCE: So why did he want to save that building? HENLEY: Well he was a preservationist at heart – he was into Old Sacramento, he was already the historian for Old Sacramento – they’d already done the master plan for Old Sacramento and this was one of the buildings that was deemed to be historically one of the more important buildings, they associated it with Sam Brannan, which was not true. PRINCE: Oh, it’s not the Brannan building? HENLEY: Well, it’s called the Brannan Hotel, or Vernon Brannan Hotel, it actually is not, it has a more innocuous name – I think it’s historic name was Jones Hotel. [Laughter] PRINCE: Oh. HENLEY: But Brannan owned the adjacent property, and he may have owned that property at some time in time, but not to build that building. PRINCE: I see, I see. So now, this was what, about ’66? HENLEY: ’65. PRINCE: Now, so then the historic district, in fact, I have something here – I’m holding a copy of a program for the dedication of Old Sacramento as a National Historic Landmark, and this was also in commemoration of Sacramento’s 126th birthday, and it’s dated August 21st, 1965, I think Dr. Aubrey Neasham was involved in this, were you around for this event? HENLEY: Actually, I came in September. PRINCE: You came in September. So you came right after this had happened. HENLEY: Right after this had happened, yeah. PRINCE: So, then the Old Sacramento, that area – had already been designated as a historic landmark. HENLEY: Yes, actually I think the thing was designated as a landmark in something like 1963 – the application was done, or ’64, something like that. And the dedication of a plaque occurred in 1965. PRINCE: Oh, okay. And this before … HENLEY: The plaques down there, next to the freeway. PRINCE: Yeah, I’ve seen the plaque, it’s sort of hidden down there in the … HENLEY: In the plaque land, the plaque wall. PRINCE: In the plaque land … right. So, Dr. Aubrey Neasham, was … was he the president of the Sacramento Landmark Commission? He was a part of that right? HENLEY: Well, Aubrey was … here’s his involvement in Old Sacramento, sort of the longest term to his leaving. Aubrey was the Regional Historian for the National Park Service in the 1940s and early ‘50s. And he did survey work frequently for the National Park Service at that time – he did a survey of Hawaii, and the Illiani Palace, he did the survey of Alaska for its historic cultural resources for the National Park Service. And his – he became fascinated with the concept of historic districts and where his interest was – he felt you could save isolated buildings, but it’s far more meaningful to save groups of buildings and environments in which they sit than to simply save an isolated building. And he had great interest in that and he was involved in lots of historic districts but in the case of Old Sacramento, as redevelopment went in, something triggered the Park Service to look at the area. And he wrote a report, late 1940s, I think, 1948, or 49, something like that. Actually, he left the Park Service before that – probably it was in 1947, or ‘48. He wrote a report that said that the West End of Sacramento had more nationally important historic buildings in a single setting than any place in the country. PRINCE: In the country? HENLEY: In the country. PRINCE: Wow. HENLEY: And that document he picked up and used in roughly 1948. He’d come to work for the State Park System, became a State Park Historian. And the State Park Historian in the 1940s was a much stronger entity than a historian would be in State Parks now, it was almost equivalent to a deputy director. And he was very close to the Drurys – both Newton Drury, and Aubrey Drury – who are, you know, they’re big names in the preservation field and in the park business, one is State Park Director, and also National Park Service Director, and back and forth. Anyway – Neasham used that language to help promote historic districts and – well, in Sacramento, but he was on a jag, doing that in California and they were using the centennial of the gold rush, 1949 as sort of a pivotal political push, or a public push to create these things, and so they got a historic district for Columbia. They got a historic district for Los Angeles, called Olvera Street, Old Town San Diego, Monterey, Bodie – which is probably one of Neasham’s best efforts – and Old Sacramento. By the time they got to Old Sacramento, which was the last historic district that Neasham was seriously involved in, he had evolved another kind of concept and that was that you just couldn’t keep creating historic districts and have them picked up by the government as … like the historic house museums, a historic district that is not a viable commercial area – he came to realize there has to be some viable commercial use to some of these areas if we’re going to keep saving them. And so he’s very interested in the concept of commercial involvement in historic preservation. Started in Columbia, but it never really happened there. They started a concession operation concept, the parks department would put concessions in – and they’re still doing that – but when it came to Old Sacramento they said, “There’s a possibility here for something else – redevelopment. We could maybe, do a historic development as a redevelopment project.” PRINCE: Ah ha. So that was the difference than the other historic districts that he’d been working on … HENLEY: That’s exactly right, and in that process of thinking he met a guy with the Redevelopment Agency named Donald Kline. And Donald Kline was the – I’m not even sure, he was like a Deputy Director, literally, of the agency, he was the chief planner for the Redevelopment Agency. Kline had come from Washington D.C. where he had had a strong involvement with the Truman administration in restoring the White House. He had a long connection with federal people involved in preservation or historic issues. So he and Neasham fed each other, literally on this idea and it kind of ballooned up to the point where they decided, maybe they could convince the feds as redevelopment, to fund a study to create a historic urban renewal district. And so, at the same time, Neasham could work the state side of it to try to create a state park as part of it. PRINCE: So that would help with the funding of it. HENLEY: Yeah. And so they went to the feds, essentially with an idea that well, we can get some local money, and we can get some state money, but we need significant federal money to do a master plan. And they did. They agreed to it. PRINCE: The federal government did. HENLEY: The feds did. And so there became a plan, which we call the Candeub and Fleissig Report. And Candeub and Fleissig are a planning and architectural firm that specialize in redevelopment activities, I think in New Jersey. They hired a firm out of Berkeley to be their architectural firm here called DeMars and Reye. Vernon DeMars, the principle, was the head of the architectural school at Berkeley, and Vernon was the architect for the Zellerbach Hall at Berkeley, and a number of really significant projects on the campus. PRINCE: Vernon Demars. HENLEY: Vernon DeMars. He was originally from MIT. They hired as historical consultants, for the project, a company called Western Heritage, Inc., which was Neasham. PRINCE: Yep. Now he founded that company, right? HENLEY: That’s correct. PRINCE: Now was he still with the state parks, or he had left? HENLEY: He had just left state parks. PRINCE: And now he was doing this independently. HENLEY: Yeah. He had left state parks and had gone to Sac State and became a professor and created Western Heritage Inc., and they were doing all these … Western Heritage Inc. might have been around a while – he may have had it for six or eight years before they did that project because he did some work for the Department of Education for the state – some historic things for fourth grade teachers and various educational packages. And he was not in this alone, you can’t form a corporation alone, you know, you’ve got to have at least a president and a secretary, and you know, and actually, you need some seed money, and he never had a lot of money to put into it so he had to get somebody to back him. His partner in this was a guy named Donald Segastrum. And Segustrum owned the newspaper in Sonora, and was a family that had gold-mining interests and had done very well in the mountains. And he and Segustrum were sort of hand in hand in the development of Columbia as a state park unit. So that’s how Neasham got to his role in Old Sacramento, but by the time he left the state park system, went to Sac State to teach and had Western Heritage, he also convinced – or played a pivotal role in convincing the city to establish a Historic Landmarks Commission for the city, and it was carried by a councilman, who later became the county auditor. [End of Tape 1, Side B]