The slopes of Mount Carmel: Nakba Ronit Lentin

advertisement

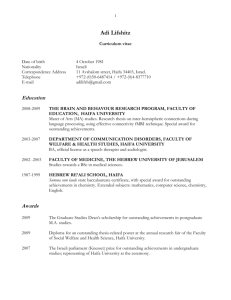

The slopes of Mount Carmel: My (Israeli) Nakba story of the 1948 fall of Haifa 1 Ronit Lentin Department of Sociology School of Social Sciences and Philosophy Trinity College Dublin rlentin@tcd.ie Prologue All biographies like all autobiographies like all narratives tell one story in place of another story (Hélène Cixous, 1997: 178). In April 1948 the Jewish militia, the Haganna, overcame the Palestinian population of Haifa, bringing about the fall of Arab Haifa and the decimation of its Palestinian community, in the course of the 1948 IsraeliPalestinian war, which the Israelis call their War of Independence, and the Palestinians their Nakba, or catastrophe. Like Carolyn Ellis (2004), who defines autoethnography as ‘writing about the personal and its relationship to culture… an autobiographical genre of writing and research that displays multiple layers of consciousness’ 1 (p. 37), I refuse to apologise for foregrounding the personal or to try to persuade sociologists that my writing is sociology. This paper combines my story – a Jewish-Israeli woman born in Haifa, Palestine prior to the establishment of the Israeli state, brought up in Israel and working and living in Ireland – with the story of my father, Miki Salzberger, who was one of the Jewish foot soldiers who conquered Haifa, set against the contested accounts of the fall of Arab Haifa. More precisely, it is an autoethnographic account of the consequences for me of my father’s involvement in the war of Haifa. As Hélène Sixous (1997) would have it, this is a story about someone else’s story, a story about memory, someone else’s memory, but also my own memory and postmemory, received through fragments of nearly forgotten fragments. Maurice Halbwachs (1992) reminds us that ‘it is in society that people normally acquire their memories… [and] recall, recognise, and localise their memories’ (p. 38). But as memory is always an act of collaboration, hence co-memoration, this is the story of co-memory, memory acquired not only ‘in society’, but also in conquest, constructed, unlike history, in collaboration with the conquered other’s ‘another story’. This is a story about Palestine – indelibly woven with the history of Israel – co-memoration of victor and vanquished. Father, an introduction Of all his immigrant friends my father had been in the country the longest – he migrated to Palestine in 1925 as a child of thirteen from Vienna, his parents having moved there in 1915 from Gura Humorlui, a country town in the northern Romanian province of Bucovina, then part of the AustroHungarian Empire, into which Jews were imported to form the commercial 2 and cultural German-speaking elite. Of all his stories about the Vienna of his childhood, I particularly liked the story about cheering Kaiser Franz Joseph, whose gilded carriage and white horses he had never forgotten. Having moved to Vienna at the age of three, he knew little about his Bucovina birthplace. The only thing he, or someone else, told us, his three children, was that his mother had him late, embarrassed at becoming pregnant at 45. A sickly baby, he was named Michael after the angel. What a start, life as a mistake… In 1925 Michael-Miki and his parents were brought to Jerusalem by his brothers – 20 and 24 years his elders. His father Jacob Salzberger was a luft mensch,2 married off to Bertha Shapira, the daughter of a wealthy family, because he was said to be scholarly. He turned out to be neither scholarly, nor a businessman. He managed to somehow send his oldest son to medical school, but his second son, like him, was a dreamer and a schemer. The Salzberger family history demonstrates how biographies often tell larger social stories, raising public questions in their social, economic and political organisation (Back, 2007: 23). Miki’s oldest brother, Motti, an ear nose and throat specialist, who was often called to fish out bones from Jewish throats on Friday nights, became a respected Jerusalem physician, with many wealthy Jerusalem Palestinians among his patients. Motti married Vera, a beautiful Jewish Russian revolutionary, but he left her for another woman; after his death, his second widow married one of his wealthy Palestinian patients and his children met their Palestinian half brothers and sisters only after East Jerusalem was occupied by Israel in 1967. Miki’s was a typical immigrant Jewish boyhood in Jerusalem, Palestine. He studied at the best Jewish secondary school, where he was 3 mocked for his foreign accent, yet worked hard at passing for a sabra 3 and resemble his school friends – most of them also children of recent immigrants. I look at his early photographs and see a dark eyed, European boy in a sailor suit (see figure 2), so different from the ideal type rougher, barefoot Israeli children of the time. But Miki loved to speak about being amongst the founders of Hamachanot Haolim youth movement, constructing a nativist sabra auto/biography from what was an immigrant childhood (Lentin, 2000). But then everyone was an immigrant – apart, that was, from the local Palestinians. Miki’s Jerusalem childhood had always seemed magical to me, invoking a longing for Palestinian East Jerusalem, the city beyond the wall which I got to know only after the 1967 occupation when it became possible for Israelis to visit the Old City. But Miki did not stay in Jerusalem. Having studied engineering in Prague, he worked for the British state oil company in Iraq and then found a job in Haifa, where he met my mother Lia Schieber, the daughter of a wealthy timber merchant from Bucovina. Lia got a job with the British airforce in Haifa, rented a room from Miki’s brother’s family, and so Haifa became my accidental birthplace. Identity and co-memory I am currently researching the co-memoration and appropriation of the 1948 Palestinian Nakba, or catastrophe. The Israeli Jewish intellectual network Zochrot 4 focuses on the Nakba in Hebrew, not merely in relation to taking responsibility for the ethnic cleansing of Palestine (Pappe, 2006), but also to its members’ Israeli-Jewish identity. 4 Though I agree with Zochrot that taking responsibility for the Nakba is crucial to being a Jewish Israeli (even though very few Israelis acknowledge this responsibility), I am determined to remember that this is not the main part of the story. Elsewhere I document Zochrot’s activities which include a focus on the testimonies of Palestinian refugees (Lentin 2007; 2008). However, while using victims’ testimonies offers the Israeli comemorators of the Nakba a certain feel good factor, my premise in this paper is that the testimonies of Israeli perpetrators are much harder to collect. Since the 1980s, the work of so-called Israeli ‘new historians’ (e.g., Flapan, 1987; Morris, 1987, 1994, 2000, 2002, 2004; Pappe, 1988, 2006) began mining Zionist and Israeli state archives for accounts of the perpetrators’ acts. However, there has been little serious attempt to excavate the personal stories of Jewish pre-state soldiers who carried out the expulsions, expropriations, massacres, rapes and ethnic cleansing. There are few exceptions. One is the Masters dissertation by Theodore Katz in which he studied Israeli veterans’ testimonies of the massacre in the Palestinian village of Tantura, which, however, provoked much acrimony and a legal challenge (Katz, 1998; Esmeir, 2007). Another is Benny Morris’s study of the diaries of Yosef Nachmani, one of the architects of Jewish settler-colonialism in Palestine (Morris, 2000; Karpel, 2005). Nachmani’s diaries in particular open a window on Zionist dualism, between Jewish idealism and the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Having served in the underground Jewish policing force Hashomer in the 1920s and 1930s, Nachmani purchased arms for the pre-state militias and Palestinian lands for Jewish settlers. Differentiating between ‘good Arabs’ and ‘bad Arabs’, he believed in co-existence, albeit one based on Jewish domination and on the transfer of Palestinians beyond the boundaries of the putative Jewish state. 5 Nachmani’s diaries denote a deep moral consternation shedding light on the dark side of the 1948 war, from the massacres and expulsions of innocent villagers, to the looting and robbery which accompanied almost every Jewish victory. Yet, according to Morris (2000), he omitted to mention ‘the link between these events and his own actions, which, for decades, aimed at the expropriation and expulsion – albeit legally and with financial compensation – of the Palestinian villagers’ (p. 102).5 Nachmani’s story reveals Zionism’s Janus face: on the one hand a self perceived morality, consideration, and compromise – wishing for ‘coexistence’ with the Palestinians on what both peoples call ‘the land’; and on the other, a destructive, selfish and power-drunk racism – which, according to Morris (2000), accord Zionism its ‘internal self righteous force… making it unstoppable’ (p. 103). I read Nachmani’s biography as a prism through which to co-memorate the Nakba, and link the story of the dispossessed Palestinians with the perpetrators’ story, with particular emphasis on the story of the 1948 war in Haifa and my father’s part in it. This autoethnographic paper, which tells, as Cixous (1997) puts it, one story in place of another story, is part of my attempt to find clues to what led me to a lifetime of opposition to Israeli state policies. Most antiZionist Israeli Jews have their ‘road to Damascus’ tale, as to when the penny dropped, usually in the wake of the 1967 war, or the 1982 Lebanon war. This story is part of my rather longer Damascene realisation, which has to start with the Haifa Nakba and my father’s part in it. However, accessing the perpetrators’ testimonies remains fraught and, in father’s case, an impossible task, since I never interviewed him before his untimely death at 62 in 1974, my own age now. In Les Back’s (2007) book on sociology as the art of listening he reminds us not only that ‘thinking, talking and describing is 6 always betrayal’, but also that ‘as a partner in thought, death may offer an orientation to life itself’, citing Saul Bellow’s remark that ‘Death is the dark backing a mirror needs if we are to see anything’ (p. 4). My father’s premature death, but also the deaths of so many Palestinians, make writing this paper necessary, though it is far from being an apologia. Rather, against the background of the parallel narratives of the battle for Haifa, it is an archaeology of the involvement of one reluctant perpetrator in the fall of Haifa, and the consequences for his anti-Zionist exilic daughter. Critical autoethnography is ‘located within a larger historical, political, economic, social and symbolic context … Such writings often offer a passionate, emotional voice of the positioned and explicitly judgmental fieldworker’ (Van Maanen, 1995: 9-10, cited in Ifekwunigwe, 1999: 43). However, I must constantly remind myself that in researching Palestine, as in co-memorating the Nakba in Hebrew, the Palestinians often get erased, their voices subsumed by the voice of the powerful coloniser. Israeli autoethnographic accounts such as this one, while motivated by empathy and solidarity, always involve a degree of appropriation which we are all guilty of, because too often, in speaking about Palestine we speak about our own subjectivity, our own politics, our own identity. Haifa, Palestine I am not sure why Haifa never felt like home. Perhaps, like the tortured, and much loved, Israeli poet Leah Goldberg, I always felt there like a ‘wild flower’, a ‘weed’, or, in my better moments, like ‘a tree in the darkness of 7 the forest, chosen by the light to reflect upon’ (Goldberg, n.d 6). This foreign feeling might have been due to the thick shadows cast by the Haifa Nakba, but as soon as I could, I moved to Jerusalem, which I regard as my Israeli home. There is a gap between the Palestinian image of Haifa as a Nakba symbol and the Israeli image of the city as a model of Arab-Jewish coexistence, an image that wilfully ignores the complete destruction of Haifa’s old city and the erasure of its Ottoman past (Yazbak, 2007). In her study of the Palestinian neighbourhood Wadi al Saleeb, destroyed during the 1948 war, resettled by North African Jewish immigrants and demolished in the 1970s (Weiss, 2007: 18), Yif’at Weiss suggests that the work of memory needs to slow down the near-total erasure of Palestinian Haifa, so as to put the mirror to its previous inhabitants, whose existence continues to cast a long shadow on the city which became Jewish in one fell swoop. I want to put the dark backing to the mirror of Haifa’s previous inhabitants, making visible the contested histories of the city and its 1948 battle. Because of the deep personal resonance the story of the fall of Haifa has for me, I am inspired by Liz Stanley’s (1996) theorisation of ‘research as necessity’, and Donna Harraway’s (1998) ‘situated knowledge’ and ‘embodied objectivity’, both of which make the juxtaposition of contested narratives a vital component of this story as it unfolds. Though mostly agrarian, a third of pre-1948 Palestine’s Arab population lived in cities. Manar Hassan (2005) critiques the erasure of the Palestinian city from both Israeli and Palestinian collective memory, resulting in ‘imagining Palestinian society as a rural society… (making it is hard) to believe that historic Palestine, that is pre-Nakba Palestine, consisted 8 of real cities’ (p. 197). 7 Haifa, situated on the Mediterranean Sea at the foot of Mount Carmel, was the largest of these real Palestinian cities. The Palestinian story tells of Haifa gradually developing from a fishing village to a major seaport due to its strategic importance to both the British who had a mandate to govern Palestine, and to the Zionists. Though Haifa’s origins are ancient, the present day city dates to the late eighteenth century when it was established by Zahir al-Umar, the strongman of northern Palestine. Haifa was briefly conquered by Napoleon’s army in 1799 before coming under direct Ottoman rule in 1840. In 1869 German farmers from the religious Templar Society settled in Haifa and in the 1880s, before the onset of political Zionism, Jews began migrating from Europe. Haifa was transformed by the period’s global economy – by World War I, Haifa replaced Beirut as the main port serving northern Palestine, southern Syria and Transjordan. The city’s development was accelerated during the British mandate, as Haifa became the terminus of an oil pipeline extending from Iraq, housing an oil refinery (www.palestineremembered.com). At the beginning of the nineteenth century there were 4,000 Palestinians in Haifa, and between 1918 and 1944, the year of my birth, Haifa’s population grew from 15,000 to 130,000, half Jewish and half Palestinian, mostly Muslim but with a significant Christian minority (Goren, 2006). By the time I was born, most Jewish people lived in Hadar HaCarmel, half way up the mountain, where my parents had their first apartment, and on the mountain itself, where we moved as father’s business improved. Most Palestinians, employed in British army bases, the oil refineries, the port and railway services, lived downtown, with a significant wealthy professional and business Palestinian elite, living on Mount Carmel. 9 The Israeli story gives a different version of Haifa as a model of coexistence, a rich texture of nationalities and ethnicities living together in harmony and tolerance in a secular atmosphere (Goren, 2006), a city of immigrants, both Jewish and Palestinian, who established a mixed economy based on Haifa’s strategic position, with Jewish people using their ‘professional skills and international connections’ and Arabs their ‘labour, and links with the Arab markets’, making Haifa a ‘working, open city’, whose many industries lay the foundations for Arab-Jewish cooperation (Goren, 2006: 37-8). Israeli scholars also narrate Haifa as an ‘urban Zionist project’, the only city constructed as a ‘semi-kibbutz’ or ‘semi-city built of suburban units’, a mixture of western city-centre welfare garden-city neighbourhoods and Bolshevik industrial suburbs, enabled, after 1948, by the re-allocation of what was designated ‘deserted’ Palestinian property to poor North African Jewish immigrants (Weiss, 2007). However, Arab Haifa disappeared instantly in April 1948. comprehensive study of the parallel accounts and A contradictory historiographies of the 1948 battle for Haifa, and of the events leading to the de-Palestinianisation of Haifa and the ghettoisation of its remaining Palestinians (Pappe, 2006) is beyond the scope of this paper. However, in order to flesh out and re-imagine my father’s role in the fall of Palestinian Haifa, I need to briefly describe the battle. The battle for Haifa: Israeli versus Palestinian narratives The fate of ‘the mixed city’ of Haifa was sealed on the night between 21 and 22 of April 1948, when members of the local Palestinian national committee met in the home of the manager of the Arab Bank of Haifa. Having 10 understood that defeat was imminent, the following morning they went to the British commander of Northern Palestine, Major General Hugh Stockwell, asking him to convey their surrender to the Jewish leadership. That afternoon the Palestinian national committee met the Jewish leadership in the town hall to applause by scores of Jews, Haifa having already been conquered by the pre-state Jewish militia, the Haganna, to sign away their city. The positivist Israeli historian Tamir Goren (2006) tells the Jewish story of the battle for Haifa; his, and probably father’s, is a story of Arab ‘riots’ in reaction to the rise of the Zionist movement and the support of the British. According to the revisionist Israeli ‘new historian, Ilan Pappe (2006), however, operations in Haifa were retroactively approved and welcomed (though not necessarily initiated) by the Consultancy, an ad hoc group of Zionist leaders assembled solely for the purpose of plotting and designing the dispossession of the Palestinians. The Haganna’s report of the coordinated operation in Haifa is a story of heroism and danger: As the British evacuated the city, our units began to immediately take key positions, capturing transport routes and army posts. Our units took… the governor’s house, Hadar HaCarmel’s police station, the railway offices… Yesterday afternoon our units attacked and captured the Headquarters in Salah A Din Street overlooking Wadi Rushmia and the eastern city exit. The enemy tried several times to take the building from us, but was defeated… The boundary between us and the enemy moved forward and most of our new positions were in Arab houses. Many enemy bases were captured by our forces…At 11 dawn our units attacked Arab Halissa… all houses were captured after heavy fighting. Arabs are abandoning the neighbourhood… getting women and children out… The enemy suffered many losses in life and property… (HaHoma, cited in Goren, 2006: 206). Goren’s book has photographs of armed Haganna soldiers patrolling Arab Haifa harassing the local Palestinians (see figure 3). Although extremely difficult for me, I am intent on editing father into these pictures. Dressed in khaki shorts and knee-length khaki stockings, he could easily have been one of those part-time soldiers who believed passionately in the need to Judaicise Haifa. He said little, but I know he was one of the foot soldiers guarding Wadi Rushmia; my bother, born in 1948, five days after the declaration of the Jewish state, remembers being told that while father was on guard duty in the Wadi, mother, in labour, was brought by ambulance to the hospital and the ambulance was shot at. The Jewish operation in Haifa was given the ominous name of ‘Operation Scissors’ indicating a pincer movement and cutting the city off from its Palestinian hinterland. Since Haifa was allocated in the 1947 UN partition plan to the Jewish state, the Jews were determined to gain control of the port, but without the city’s 75,000 Palestinian inhabitants; in April 1948, they achieved this objective (Pappe, 2006). Pappe outlines the part played by the British in the fall of Haifa – intended to leave the city in May 1948, British troops were present as Jewish units captured the Palestinian parts of the city. According to Pappe, British politicians later admitted that the British conduct in Haifa forms ‘one of the most shameful chapters in the history of the British Empire in the Middle East’. 8 12 Pappe’s (2006) description of the fall of Haifa is far less sanitised than Goren’s: ‘The Jewish campaign of terrorisation, begun in December 1947, included heavy shelling, sniper fire, rivers of ignited oil and fuel sent down the mountain-side, and detonated barrels of explosives, and went on for the first months of 1948…’ When, on 18 April, the British informed the Jewish authorities that their forces were to leave the buffer zone between the Jewish forces and Haifa’s Palestinians, the road was open for the de-Arabisation of Haifa (p. 93-4). I am trying hard not to sound sanctimonious, but I have a desperate need to speculate whether father was one of the 2,000-strong well armed Carmeli Brigade Jewish soldiers facing a poorly equipped army of 400 local and Lebanese volunteers who had inferior arms and limited ammunition, a poor match to the armoured cars and mortars on the Jewish side. The removal of the British barrier led to ‘Operation Scissors’ giving way to Operation ‘Cleansing the Leaven’.9 While the city’s Jewish mayor, a decent man by all accounts, beseeched Haifa’s Palestinians to stay, promising no harm would befall them, Haganna loudspeakers were urging Palestinian women and children to leave before it was too late, and the Carmeli commander issued explicit orders to his troops to ‘Kill any Arab you encounter; torch all inflammable objects and force doors open with explosives’ (Pappe, 2006: 95). Though painful, I must imagine father as one of those who torched objects and forced doors open, and even killed, as the bewildered Palestinians, without packing their belonging, or knowing what they were doing, began leaving en masse, heading towards the port. But I would never know whether father was one of the troops who, once Palestinians left their homes, broke into and looted their houses. 13 Pappe (2006) reports that at dawn on 22 April, the people came streaming into the harbour. The streets in the Palestinian part of the city were overcrowded and the Arab leaders tried to instil some order in the chaos. Loudspeakers could be heard asking people to gather in the old marketplace near the port until an orderly evacuation by sea could be organised. The Carmeli Brigade war book shows little compunction about what happened next. Aware that people were advised to gather by the port, Jewish officers ordered their men to station three-inch mortars on the mountain slopes overlooking the market and the port and bombard the gathering crowds below. The idea was to ensure that the flight would be in one direction only; as Palestinians gathered in the beautiful old Ottoman marketplace, they were easy targets for the Jewish marksmen (Eshel, 1973: 147, cited in Pappe, 2006: 96). As the shelling began, the crowd broke into the port, storming the boats moored there. According to the Palestinian historian, Walid Khalidi: ‘Men stepped on their friends and women on their own children. The boats in the port were soon filled with living cargo. The overcrowding in them was horrible. Many turned over and sank with all their passengers’ (cited in Pappe, 2006: 96). House to house searches, arrests and beatings meted out to those who did not leave during these fateful days in April meant that even those who delayed decided to leave. By 1 May only some 4,000 Palestinian were left in Haifa (Morris, 2000: 35-6). Why did they leave Haifa? Every Palestinian must have asked his or her parents the same question: why did you leave? I imagine that the answer comes always 14 in two stages: first, there are the obvious explanations, the threats, the bombs, the rumours of massacres, the death of close ones, as well as the great fear of rape, the traditional Palestinian man and woman’s paramount anxiety about the loss of honour. Then, after a moment’s silence, there comes the doubt as he or she examines his or her memories, which have, perhaps, begun to fade. Guilt then sets in, embarrassment, a whispering, nagging scepticism: what if I had been cowardly, what if… (Al Qattan, 2007: 203). The story of the de-Palestinianisation of Haifa is debated around the key question of whether, as argued by Israeli historians, and as my father told it, Haifa’s Palestinian population was instructed by its leaders to evacuate the city despite being asked to stay by the Jewish leadership; or whether Haifa’s Palestinians were ethnically cleansed, as argued by Palestinian historians and revisionist Israeli scholars such as Ilan Pappe (2006). Typically, Goren (2006) argues that the Jewish leadership tried hard to prevent mass evacuation and that the testimonies of Jews, British and Palestinians alike confirm that ‘no steps were taken to encourage the Arabs to leave the city’ (p. 228). But in recent years the story has become more nuanced. Israeli scholars report the desertion of Haifa by the Palestinian elite who evacuated their families even before hostilities broke, resulting in Haifa’s Arabs remaining leaderless (Pappe, 2006: 93). Israeli historians also stress the structural weaknesses of Palestinian society (Morris, 2000) and the Palestinian national committees which were unable to bring about unity and prevent Palestinians from leaving (Goren, 2006) as major factors in the defeat. According to Goren: ‘Haifa’s Arabs were cut off… the committee 15 brought about the fall of Arab Haifa. ..’ (p. 244). However, current Israeli historiography supports the Palestinian insistence on the active role the Haganna played in the de-Arabisation of Haifa (Weiss, 2006). But what about father’s version? I remember him telling me that Haifa’s Jews begged the Palestinians not to leave the city. By all (Jewish) accounts, some Jews did try. Weiss (2006) says the Jewish leadership was hugely embarrassed, though she notes that the embarrassment might have been due to Haifa’s Jews worrying about losing cheap Arab labour. After the initial embarrassment, however, Haifa’s Jewish leadership stopped calling upon the Palestinians to stay. Morris (2000) argues that mass Palestinian evacuation wetted the Jewish appetite: ‘everyone… understood that a Jewish state without a large Arab minority would be stronger…Jewish atrocities … also contributed to the evacuation’ (p. 27). A month after the fall of Haifa, a Jewish commentator declared, ‘at first [we] were interested in keeping the Arabs… then another idea set in, better without Arabs, it’s more convenient’ (Morris, 2004). Interviewing my dead father? I do want to come back to Miki, who never spoke about his childhood, and who did not say much about his wars. Like the lives of so many twentieth century Jews, his life was punctuated by wars. He was born two years before the onset of World War I on the outskirts of the Habsburg Empire. Unlike mother’s family who escaped Romanian Bucovina to the safety of the Hungarian part of the province during World War I, Miki’s father took the family to Vienna, where Miki saw his Kaiser. But this is all I know. Once or twice, when, as a picky eater, I refused to eat chicken or potatoes, he 16 muttered something about how lucky I was not to have experienced hunger, said he had to eat potato skins, though he never made it clear whether this was during his Vienna childhood, or his time in Prague as an impoverished engineering student. He would also say that we were lucky to be the first generation of Jews not to experience antisemitism – probably granting me the confidence to rebel against that very state of majority rule over the occupied Palestinians. He said little and only insubstantial narrative fragments survived. The old Parabellum pistol he hid in the linen cupboard for mother to defend herself when he was on Haganna guard duty was returned to the police in the 1960s, after it was discovered by my teenage brothers. He never said whether he had used it and if so, doing what. But the photographs in Goren’s (2006) book keep troubling me as I desperately edit Miki into the picture. I know he stood guard at the Haganna posts, but was he there when Palestinian refugees were led in lorry-loads to the harbour? Did he patrol the demolished old city? More crucially, did my father, the sensitive young immigrant whose family escaped the outskirts of the empire, witness his city’s Palestinian refugees leave their homes with hastily packed belongings, carrying them in sack loads on their bent backs (see figure 4)? I cannot ask him now, but it probably never occurred to father to tell us about his role in the Haifa Nakba. The comparison with ‘ordinary people’ who served in the Nazi Wehrmacht troubles my mind, as does the discovery, in the late 1960s, by the ’68 generation, children of German soldiers, of what their fathers did during the war. Listening to an Israeli interviewee in Dalia Karpel’s (2005) film about Yosef Nachmani talking about shooting a dozen crouched Palestinian refugees hiding in a deserted building, and saying he 17 has no regrets even though some of this friends called him ‘Nazi’, it may not be such an odd comparison after all. Building auto/biographical memory sites: Co-memory, post memory Why do some people have the power to remember, while others are asked to forget? … No ethical person would admonish Jews to forget the Holocaust… yet in dialogue with Israelis… Palestinians are repeatedly admonished to forget the past… ironically Palestinians live the consequences of the past every day – whether as exiles from their homeland, or as members of an oppressed minority within Israel (Bishara, 2007). Pierre Nora’s article on memory sites, which helped inaugurate a ‘memory boom’, can be read as an elegy for the decline of ‘authentic’ memories. Nora argues that we continue to speak of memory because there is so little of it, and contrasts ‘real memory – social and unviolated’ (Nora, 1989: 8) in so-called ‘primitive’ societies and among peasants, with contemporary memory. Claiming that we can retain sites of memory because this is the best we can do now there is no spontaneous memory, Nora writes that ‘lieux de mémoire are fundamentally remains, the ultimate embodiments of a memorial consciousness that has barely survived in a historical age that calls out for memory because it has abandoned it’ (p. 12). According to Nora, with archives being kept not only by states and large institutions, but by everyone, memory becomes an individual duty, and lieux de mémoire come in various shapes as ‘memory attaches itself to sites, whereas history attaches itself to events’ (p. 22). 18 Debates on the centrality of memory in theorising catastrophic events have proliferated in relation to the Holocaust. Marianne Hirsch (1997) posits the ‘postmemory’ of the second generation, mediated through photographs, films, books, testimonies, and distinguished from memory by generational distance and from history by deep personal connection. James Young (2000) calls this ‘the afterlife of memory represented in history’s after-images: the impressions retained in the mind’s eye of a vivid sensation long after the original, external cause has been removed’ (pp. 3-4). Postmemory is one facet of ‘collective memory’, theorised as different from ‘history’ in being shaped by society’s changing needs, or, conversely, as shaping both political life and history itself. The politics of remembrance in the current ‘era of testimonies’ includes the trauma experienced by contemporary bystanders. It also entails collective forgetting, which ‘we’, who survive after the event of genocide, have to struggle with in the face of our shame (Agamben, 1999). The question is whether Nora’s (1989) theorisation of ‘memory sites’ encompasses ‘sites of silence’, where the landscape itself becomes the site of memoricide rather than memory, as Pappe (2006: 226) argues in relation to the reinvention and Hebraicisation of Palestine’s geography by the Israeli state. Whether or not Arab Haifa is such a ‘site of silence’, it is certainly a site of co-memory, a memory site I have constructed in collaboration with the vanished Palestinians, with those Palestinians who did remain in the city I grew up shadowing my Israeli-Jewish childhood and youth. In reality, Arab Haifa, and in particular Wadi al Saleeb, was largely demolished. The story of the 3,500-5,000 Palestinians left in Haifa after the Jewish troops cleansed the city on 23 April 1948 exemplifies the tribulations of the Palestinians under occupation since that war. Pappe (2006) tells that on 1 July, the Israeli commander of the city summoned the leaders of the 19 remaining Palestinian community to ‘facilitate’ their transfer from the various parts of the city where they were living into one downtown neighbourhood, Wadi al Nisnas, one of the city’s poorest areas. Some were told to leave their residences on the slopes of Mount Carmel within four days. The shock was enormous – many of Haifa’s Palestinians belonged to the Communist Party that had supported partition and hoped that now that the fighting was over, they would live peacefully in the Jewish state whose establishment they did not oppose. Despite protests by the leaders, who called the move ‘ghettoisation’, the Palestinians were commanded to leave and told they would have to cover the cost of their forced transfer. In their new abode, Wadi al Nisnas, which serves today’s municipality to cynically celebrate the convergence of Hanuka, Christmas and Id al-Fitr as ‘the feast of all feasts for peace and coexistence’, they were continually robbed and abused by Irgun and Stern Gang 10 members, with the Haganna standing by and doing nothing (Pappe, 2006: 207-8). Today, above al-Istiklal mosque and below Hadar HaCarmel stands the large demolition site of Wadi al Saleeb. According to Weiss (2006), Israelis know it because of the ‘riots’ by its North African Jewish immigrant residents in 1959, but few remember it had been a Palestinian Muslim quarter. Over the years there were various plans to turn it into an artists’ quarter, but as the Palestinian academic Raef Zreik (2007) says, ‘fifty years have passed and a new quarter has not yet been built for the Palestinians in Haifa. We have not demanded a new quarter in Haifa’. For me Haifa is a lieu de mémoire, or perhaps a lieu de silence, where I attempt to co-memorate Haifa’s Palestinian past together with my Palestinian friends and colleagues, dreaming the impossible dream of a secular democratic Palestine. But this is another story for another day. 20 Reflections: My father, his daughter If Cixous (1997) is right and all narratives tell one story in place of another story, then perhaps Zochrot is also right that telling the story of the Nakba is telling our own, my own story. Does telling it as an autoethnography and speaking about father rather than about the Palestinian survivors of the ethnic cleansing of Haifa make me as guilty as Theodore Katz, who, according to Samera Esmeir (2007), argued that the contradictory, recursive testimonies of the survivors of the Tantura massacre constituted a ‘failure’ of memory? I keep wondering if I should have concentrated on reading testimonies of the Palestinian survivors of the fall of Haifa? Or would doing this perpetuate their victimhood? There are many dilemmas involved in representing my father through my ‘ethnographic I’ (Ellis, 2004). Like Ellis, I believe I was always predisposed to thinking like an ethnographer. I identify with her when she writes: ‘as a child, I constantly listened in on conversations among adults… I suspect my ethnographic instincts were present from a young age… my taste for ethnography makes life interesting, as long as I remember to balance living in the moment with writing and reflecting on the moments in which I’ve lived’ (p. 333; see also Lentin, 1989, 2000). Though my father is not available to me to check his version of events, nor am I able to seek his permission to quote from his letters to me, this paper is ultimately about my own Damascene trajectory, from an ‘ordinary’ Israeli post-Holocaust childhood to a lifelong opposition to Israeli state policies and solidarity with the Palestinian ‘other’. I borrow from Ellis (2006) the notion of taking ‘retrospective field notes’ of my life, since, apart from his letters to me, and 21 a few photographs, some of which are reproduced in this article, I have no documentary evidence to substantiate my strong feeling that my life and political commitment have been shaped by his life (though not necessarily his political commitment). Auto/biography and autoethnography are not history but rather representations of past events, assisting us in constructing, rather than re-constructing lives. Because I have no access to his version of events, this is my attempt to construct a fraction of my father’s life in relation to the political issue which I regard as central. While father migrated to Palestine not as a Zionist idealist but because his father could not make a living in pre-Nazi Vienna; he became a Zionist, bequeathing me what must be described as an ‘ordinary Israeli childhood’, compete with pre-military school training, hikes aimed to ‘conquer the land with our feet’, and a conviction that, as the Israeli popular song goes, ‘we have no other land’. But growing up in Haifa, where some Palestinians were allowed to remain, albeit concentrated in their downtown ghetto, meant seeds of doubt were sown early on. Just as I heard the stories that mother’s relatives were telling about their Holocaust experience, which they didn’t want us, the ‘real Israeli’ children, to hear, and which, having visited mother’s home town in Northern Romania, I documented in a novel (Lentin, 1989), so I also heard the background music of the Nakba. I heard it through mother telling me repeatedly how she used to mutter ‘I hate Arabs’ as she rushed to the pistol father had hidden for her in the linen cupboard when he was on Haganna guard duty, while holding me, her asthmatic baby, and minding his old mother. And through the fragments father never spoke about, but which were in the air. We were an argumentative family – from an early age father called me ‘the leader of the opposition’. Did this preordain my lifetime of dissent? 22 For years I argued with him, and after the 1967 war our arguments became politically bitter. Towards the end of his life, father became despondent. His huge achievements – he designed and produced the first Israeli-made washing machine, even though his business never prospered fully, and was an accomplished painter – did not assuage his depression. In the last year of his life, after I had migrated to Ireland, Miki wrote me a series of letters, the first just after the outbreak of the 1973 war, his last war. These letters, honest and painful articulations of his love for me and deep commitment to Israel, but also of his doubt, worry and despair, resonate for me with Nachmani’s fluctuations between revulsion at Jewish acts of wanton murder and looting and his conviction that the Jewish struggle was ‘hard, but moral… If we are to establish a state, we need… to prevent unjust revenge…’ (Morris, 2000: 71). Research always entails appropriation, and to regard his letters as mine to cite is fraught. But these letters are important to my attempt to understand him, to understand me. After his death, my mother and I have talked a lot about his depression and doubts, and about my politics, so I hope he may have agreed to my quoting some fragments (emphases added): ‘I was hoping they would mobilise me, but apparently they have enough old men…’ (7/10/73). ‘What happened this time was really awful; the fate of the nation was in doubt. There is no family in the country who has not experienced losses… everywhere you go you see tearful eyes. Let us hope that the losses would help us to move towards peace…’ (8/11/73). ‘We are all looking for developments in Geneva, even though the opening speeches were not encouraging. Hatred sounded from every 23 word and I feel we are really isolated. This makes me think that perhaps we are to blame after all’ (23/12/73). ‘As far as I am concerned, I am tired of all the victories. I would like to think that the future might bring some peace, although I am not too sure if we can live in peace. It seems to me that if the Arabs want to liquidate us, all they have to do is make peace with us…’ (22/1/74) By May 1974 his doubts were more explicit: ‘Hard times… on the one hand, the war with Syria continues, on the other, the internal situation contributes to our political isolation…Is humanity really that cruel and selfish, or is the blame in us? I find it hard to decide... After all, we did not seek wars and conquests, we merely wanted to live in peace with our neighbours, or perhaps I am wrong and we sought imperialism and oppression? … I can see no ray of hope and I don’t know what to do, how can a simple man like me express his views’ (22/5/74) I have not kept my own letters to him. I was a young mother at the time, struggling with life as a migrant in my adopted country, but I want to hope that my letters were kinder than my arguments with him had been. In his last letter, written just four days before he died of a sudden coronary, father, who had just enlisted in the civil guard, described himself as the ‘brave soldier Schweik patrolling the streets once a week… they may even give me a gun ‘(23/6/74). It is as impossible for me to fathom what went on in his mind in these final days as it is to gauge the extent of his participation in perpetrating the Haifa Nakba. Probably, like Yosef Nachmani, he believed in the justice of 24 the Zionist cause while at the same time feeling moral revulsion at the excesses of the power-hungry army. But, like Nachmani, my father bore responsibility for his part in perpetrating the Haifa Nakba, and I, his daughter, take on this responsibility, even though I believe that it was his legacy as a migrant and his assigning me the role of an oppositionist from a very young age that shaped my lifelong career of political dissent and solidarity with my Palestinian sisters and brothers. From this distance in time and place, it is Miki’s self image as the ‘brave soldier Schweik’, a comic World War I reluctant soldier, that enables me to make some sense of his soldiering – making his Nakba days somewhat easier to equate with what Esmeir calls ‘the year of conquest’, whose survivors lived on out of death, ‘their memories, as articulated by the silences, the multiple experiences, the various perspectives, are all indicators of the historical, of that which took place’ (Esmeir, 2007: 249). Notes: 1 I thank Andrew Sparkes and the two reviewers for their helpful comments. Thanks also, as ever, to my dear friends Eli Aminov and Nitza Aminov. 2 Yiddish for ‘insubstantial man’ without proper occupation or business. 3 Sabra, the Arab name of the prickly pear cactus, is an appellation used by both Israeli and Palestinian for natives of Palestine (Almog, 2000). 4 Zochrot means ‘remembering’ in the female form. For details see www.nakbainheabrew.org. 5 Interestingly, like several right-wing Israeli intellectuals who are increasingly comfortable with the idea that their country was built on ethnic cleansing, in 2004 Morris himself, despite having been one of the pioneers in uncovering the true extent of the Zionist plans to dispossess the Palestinians, declared his disappointment that the Nakba was not more thorough, saying to Ha’aretz journalist Ari Shavit: ‘When the choice is between destroying or being destroyed, it’s better to destroy’ (Shavit, 2004). 6 The full verse reads: ‘But if it happens that the gate opens / and all my body cries: here he is! / I would be like a tree in the darkness of the forest / chosen by the light to reflect upon’ (Leah Goldberg, ‘Experience’) 7 Eli Aminov (2007) goes further, critiquing the Zionist de-urbanisation of Palestine as a governmental technology. 8 Rees Williams, the Under Secretary of State’s statement to Parliament, Hansard, House of Commons Debates, vol. 461, p. 2050, 24 February 1950, cited in Pappe, 2006: 93. 9 The Hebrew word stands for total cleansing, and refers to Jewish religious elimination of traces of bread before the Passover (Pappe, 2006: 94). 10 Irgun and Stern Gang were right wing paramilitary organisations banned by Israel’s first Prime Minister after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. 25 References: Agamben, G. 1999. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. New York: Zone Books. Almog, O. 2000. The Sabra: The Creation of the New Jew. Berkeley, London: University of California Press Aminov, E. 2007. ‘The Palestinian city and Zionist de-urbanisation’, Machsom, www.machsom.com/article.php/id6362 Al Qattan, O. 2007. ‘The secret visitations of memory’, in Sa’di, A. and Abu-Lughod, L., editors, Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory. New York: Columbia University Press. Back, L. 2007. The Art of Listening. Oxford, New York: Berg. Bishara, G. 2007. For Palestinians, memory matters. It provides a blueprint for their future, San Francisco Chronicle, 13 May 2007, http://sfgate.com Cixous, H. 1997. Albums and legends, in Cixous, H. and Calle-Gruber, M. Hélène Cixous Rootprints: Memory and Life Writing. London: Routledge. Ellis, C. 2004. The Autoethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. Eshel, Z., editor. 1973. The Carmeli Brigade in the War of Independence. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defence Publications. Esmeir, S. 2007. Memories of conquest: Witnessing death in Tantura, in Sa’di, A. and Abu Lughod, L., editors. Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory. New York: Columbia University Press. Flapan, S.1987. The Birth of Israel: Myths and Reality London: Croom Helm. Goldberg, L. n.d. Early and Late: Selected Poems. Merchavia: Sifriat Hapo’alim. Goren, T. 2006. Arab Haifa in 1948: The Struggle and the Fall. Sed Boker: Ben Gurion Institute / Ministry of Defence. Halbwachs, M. 1992. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Harraway, D. 1988. Situated knowledge: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14/3: 575-99. Hassan, M. 2005. The destruction of the city and the war against memory: Victors and vanquished. Theory and Criticism 27, 197-208. Hirsch, M. 1997. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge, Mass., London: Harvard University Press Ifekwunigwe, J. O. 1999. Scattered Belongings: Cultural Paradoxes of ‘Race’, Nation and Gender. London: Routledge. Karpel, D. 2005. Yomanei Yosef Nachmani (The Diairies of Yosef Nachmani). Tel Aviv: Transfax Film Production. Katz, T. 1998. The exodus of Arabs from the villages at the foot of Southern Mount Carmel in 1948, Master’s Thesis, University of Haifa. Lentin, R. 1989. Night Train to Mother. Dublin: Arlen House. Lentin, R. 2000. Israel and the Daughters of the Shoah: Re-occupying the Territories of Silence. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. Lentin, R. 2007. The memory of dispossession, dispossessing memory: Israeli networks commemorising the Nakba. In Fricker, K. and Lentin, R, editors. Performing Global Networks. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 26 Lentin, R. 2008. The contested memory of dispossession: Commemorising the Palestinian Nakba in Israel. In Lentin, R., editor. Thinking Palestine. London: Zed Books. Morris, B. 1987. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Morris, B. 1994. 1948 and After: Israel and the Palestinians. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Morris, B. 2000. Jews and Arabs in Palestine / Israel 1936-1956. Tel Aviv: Am Oved. Morris, B. 2002. A New Exodus for the Middle East? The Guardian, October 3, 2002 Morris, B. 2004. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Nora, P. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations. 26, 7-24. Pappe, I.1988. Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1948-51. Basingstoke: Macmillan in association with St Antony's College, Oxford. Pappe, I. 2004. Response to Benny Morris, “Politics by other means” in the New Republic. The Electronic Intifada 30 March 2004 Pappe, I. 2006. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. Oxford: Oneworld Publishing. Shavit, A. 2004. ‘Survival of the Fittest, an Interview with Benny Morris’, Ha’aretz, 9 January, 2004 Stanley, L. 1996. The mother of invention: Necessity, writing and representation. Feminism and Psychology, 6/1, 45-51. Van Maanen, J. 1995. Representation in Ethnography. London: Sage. Weiss, Y. 2007. Wadi Saleeb: Confiscated Memory. Jerusalem: The Van Leer Jerusalem Institute. Yazbak, M. 2007. A city detached from reality, Ha’aretz, 22 May, 2007. Young, J. E. 2000. At Memory’s Edge: After-images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. Zreik, R. 2007. ‘Exit from the scene: Reflections on the public space of the Palestinians in Israel’. Forthcoming. 27