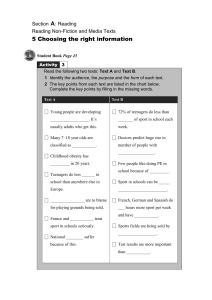

Sport Governance and European Integration Abstract

advertisement