Challenges for estimating and forecasting macroeconomic trends during financial crises:

advertisement

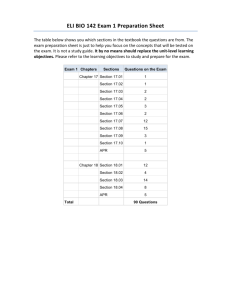

Challenges for estimating and forecasting macroeconomic trends during financial crises: implications for counter-cyclical policies Pingfan Hong Chief for Global Economic Monitoring UN/DESA International Seminar at Ottawa, Canada 27-29 May 2009 Views expressed here are solely those of the speaker and they do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations 1 Outline Introduction Forecasting performance of UN/LINK global modeling system High Frequency Modeling for Rolling estimation and forecast “turning point”: Over-year-ago (oya) Quarterly GDP growth versus Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate (SAAR) of Quarterly GDP growth The importance of correctly estimating potential output 2 Introduction Estimating versus forecasting Estimating: yte E ( yt / I t ) Forecasting: ytf E ( yt / I t 1 ) Importance of estimating and forecasting for countercyclical macroeconomic policy: timeliness, consistent, accuracy, “turning point”, and correct estimate of the potential gap 3 Forecasting performance of UN/LINK global modeling (1) Figure 1. Forecasting world GDP 7 3 1 -1 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 1976 1974 -3 1972 per cent 5 year Errors Forecasts Observed 4 Forecasting performance of UN/LINK global modeling (2) Figure 2. forecasting GDP for developed countries 7 3 1 -1 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 1976 1974 -3 1972 per cent 5 year errors forecast observed 5 Forecasting performance of UN/LINK global modeling (3) figure 3. forecasting GDP for developing countries 7 3 1 -1 -3 2006 2004 2002 2000 1998 1996 1994 1992 1990 1988 1986 1984 1982 1980 1978 1976 1974 -5 1972 per cent 5 year errors forecast observed 6 Forecasting performance of UN/LINK global modeling (4) developed economies world developing countries Mean 0.02 0.04 -0.36 Median 0.05 0.05 -0.1 0.7 0.76 1.25 Fraction of positive errors 0.52 0.5 0.42 Serial correlation -0.2 -0.1 0.29 Standard Deviation Source: DESA 7 High Frequency Modeling for rolling estimating quarterly GDP Collecting weekly data stream Principle Component ARIMA Weekly rolling estimate and forecast of quarterly GDP Sources for slides 8-12: L.R. Klein and W. Mak, University of Pennsylvania Current Quarter Model of the United States Economy Y. Inada, Konan University Current Quarter Model Forecast For the Japanese Economy 8 Example: US weekly data stream Date Economic Indicator for Latest and Prior Month Apr 01 Construction Spending February -0.9% -3.5% Apr 01 Auto Sales March 9.9 Million 9.1 Million Apr 02 Manuf Ships, Inv, & Orders February -0.1%, -1.2%, 1.8% -2.6%, 1.1%, -3.5% Apr 03 Nonfarm Payroll Employment March -663,000 -651,000 Apr 07 Consumer Credit Outstanding February -$7.5 billion $8.1 billion Apr 09 Export/Import Price Index March -0.6%, 0.5% -0.3%, -0.1% Apr 09 Trade Balance February -$26.0 billion -$36.2 billion Apr 15 Producer Price Index, Total & Core March -1.2%, 0.0% 0.1%, 0.2% Apr 14 Retail Sales, Total & Ex-Auto March -1.1%, 0.9% 0.3%, 1.0% Apr 15 Industrial Production March -1.5% -1.5% Apr 14 Business Inventories February -1.3% -1.3% Apr 15 Consumer Price Index, Total & Core March -0.1%, 0.2% 0.4%, 0.2% Apr 16 Housing Starts February 510,000 572,000 9 Example: indicators used in US model for estimating quarterly GDP Industrial Production Index Manufacturers’ orders, deflated by producer price index Manufacturers’ shipments, deflated by producer price index Manufacturers’ unfilled orders, deflated by producer price index Yield spread between 6-month commercial paper and 6-month treasury bills Real interest rate (6-month commercial paper yield adjusted by consumer price index) Real M1, adjusted by consumer price index Real retail sales, adjusted by consumer price index Real personal income, adjusted by consumer price index Real 10-year treasury yield Yield spread between 10- and 1-year treasury bills Nonfarm payrolls Average weekly hours, production workers: total private Trade-weighted value of the US dollar, nominal broad dollar index 10 Example: Equations for GDP and PGDP in US model Dlog (QGDP) = 0684 – 0.954 Dlog C1 + 0.304 Dlog C2 -0.0661 Dlog C6 – 0.295 Dlog C7 + 0.581 AR(1) – 0.677 MA(1) Dlog (QPGDP) = 0.817 – 2.463 Dlog C1 + 0.925 Dlog C2 + 1.383 Dlog C3 – 5.113 Dlog C4 + 4.189 Dlog C5 – 2.233 Dlog C6 + 0.908 MA(4) 11 Example: Japan H-F model forecast versus consensus forecast Source: Y. Inada 12 Convergence in the rolling forecast of the US H-F model 3 2 1 0 2008q1 q2 q3 q4 2009q1 offical -1 est m1 -2 est m2 est m3 -3 est m4 -4 -5 -6 -7 Mean error RMSE M1 M2 M3 M4 -2.625 -0.5475 -0.665 -0.8375 3.607652 1.853126 1.144312 1.4058 13 Convergence in the rolling forecast of the Japan H-F model Rolling estimate of GDP for Japan 5 0 2008q1 q2 q3 q4 2009q1 offical -5 per cent est m1 est m2 est m3 -10 est m4 -15 -20 Mean error RMSE M1 M2 M3 M4 -7.3 -6.7 -3.2 -0.7 8.4 7.2 4.5 2.1 14 “turning point”: oya versus saar Example of China’s GDP ytoya (Yt / Yt 4 ) 1 4 ytsaar (Yt sa / Yt sa ) 1 1 China GDP Growth: oya vs saar 16 14 12 per cent 10 oya 8 saaq 6 4 2 0 2007q1 q2 q3 q4 2008q1 q2 q3 q4 2009q1 Sources: China NBS, JPM 15 Importance of correct estimate of potential output for counter cyclical macroeconomic policy it t r * ( t * ) (1 )( yt y* ) Taylor rule: Hodrick-Prescott filter for estimating potential GDP growth : T min (y t 1 t t ) T 1 2 [( t 1 t ) ( t t 1 )]2 t 2 Production function for estimating potential GDP growth: y* f (k * , l * ) 16 Estimate of output Gap for the US economy by H-P filter US GDP GAp by H-P filter 11800 11700 11600 11500 11400 11300 USA_YGDP USA_YGDP_HP2005 11200 11100 11000 10900 20 05 Q 1 20 05 Q 2 20 05 Q 3 20 05 Q 4 20 06 Q 1 20 06 Q 2 20 06 Q 3 20 06 Q 4 20 07 Q 1 20 07 Q 2 20 07 Q 3 20 07 Q 4 20 08 Q 1 20 08 Q 2 20 08 Q 3 20 08 Q 4 20 09 Q 1 10800 17 Estimate output Gap for the US economy by production function Source: Business Week 18 Are these Output GAPs corrected estimated? Output gap % of GDP Record levels of spare capacity 6 4 2 0 -2 High-income -4 Developing -6 -8 09 10 11 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 05 10 Source: World Bank. 19 Concluding remarks It’s a big challenge to make a timely and consistent estimate and forecast for economic trends during financial crisis But they are crucial for macroeconomic policies We can make improvement 20