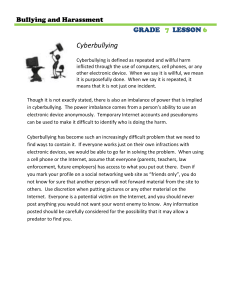

How parents can Detect, Intervene and Prevent Cyberbullying Module 3 3.1 Summary

advertisement