Document 16812387

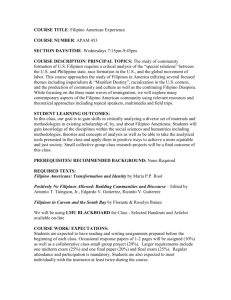

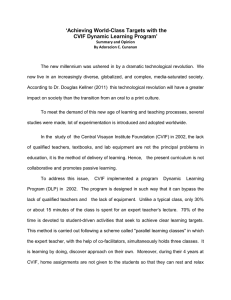

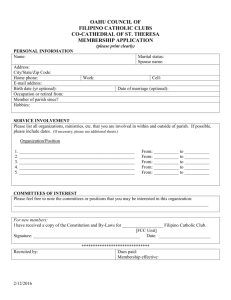

advertisement