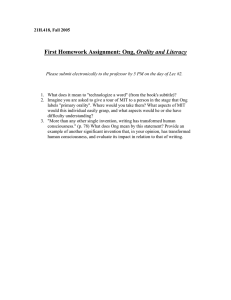

THE HEARING OF HARMONY: AUDIO ESSAYS AND SECONDARY ORALITY IN

advertisement