WOMEN’S SELF-DEFENSE AND SOCIAL INTERACTION Silke Schulz

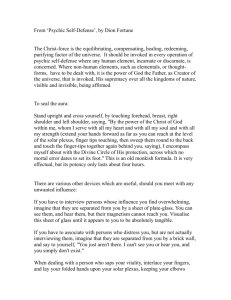

advertisement