ASEMKA A LITERARY JOURNAL OF THE

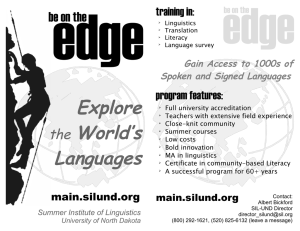

advertisement

ASEMKA A LITERARY JOURNAL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAPE COAST UNIVERSITY OF CAPE COAST GHANA No. 6 SEPTEMBER, 1989 CONTENTS Criticism African Autobiography and Literary Theory..... KWADWO OPOKU-AGYEMANG. .. Beyond Art; From Dream to Reality......... KOFI ANYIDOHO. 5 19 L'ombre de Fanon: Une étude comparée des Soleils des In dep ndences d'Amadou Kourou Ma et de l' Age d’or n'est pas pour demain d'Ayi Kwei Armah ... .. .. ..32 ATTA BRITWUM Le Chef Nanga ou une fausse représentativité: Examen du role du 'héros' dans A Man of the People .. .. .. 42 Y. S. BOAFO To Rise Again: Of Women and Marriage in Mariama Bâ’s So Long A Letter .. ........ .. 49 N. JANE OPOKU-AGYEMANG Our Literary Antecedents FABIAN OPEKU .. .. .. .. .. 69 Language Les emprunts; Qu’est-ce qu’un mot français/non français? 78 PATRICK KILSON Book Review French Language Teaching in Africa: Issues in Applied Linguistics: E. N. Kwofie .... .. .. .. 94 TUNDE AJIBOYE FRENCH LANGUAGE TEACHING IN AFRICA: ISSUES IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS E. N. KWOFIE LAGOS UNIVERSITY PRESS, 1985-155 PAGES REVIEWED BY TUNDE AJIBOYE* The appeal of the book lies in its attempt to summarize the problems and state of French language teaching in both Francophone and Anglophone countries of Africa. Of course, as the author constantly reminds us, his can only be described as an attempt at a summary given the complexity, extent and varieties of situations which French language teaching represents for the several countries of Africa where that language is used either as a foreign language like in Nigeria and Ghana or as an official language like in La Côte d’lvoire and Senegal. The attempt cannot but be seen as both courageous and enlightening; courageous because it smashes the fear of a tidy study of the problem (multifaceted as it is) being impossible; enlightening because, thanks to this work, it could be conveniently asserted that, within the temporal framework that is embraced by Kwofie's research, the problems and perspectives of French language teaching in Africa are broadly speaking, similar. There is in Professor Kwofie's book a wealth of documentation that is yet to be beaten by any writer on the subject since Dupon-chel's Le frangais d'Afrique: line langue, un dialecte ou une variete locale? (1974) and more appropriately, David's French in Africa: A guide to the teaching of French as a foreign language (1975). French Language Teaching in Africa is broken into six chapters all neatly and coherently strung together. The first chapter concerns the debatable notion of 'African' French and the question of variety choice in French language teaching. As a theoretical framework, linguistics, in particular applied linguistics, is considered in chapter 2 as a possible feeder in the task of foreign language, moreso in a multilingual, multiethnic setting like Africa. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 could be taken as sub-set of the whole set as they each deal with a chosen aspect of the teaching of French language: grammar, lexicon and pronunciation in that order. An appraisal of French language teaching should in principle, include a consideration of the evaluation procedure which serves as a tool for verifying extent of learning. This is the focus of chapter 6. Chapter after chapter, Kwofie demonstrates a clear and keen awareness of, and a deep reflexion on a question which he has been pursuing since his Teaching a Foreign Language to the West African Students (1978), (monograph), Linguistic Research Inc., Edmonton, Canada-Like the latter, the rich references are indicative of the author's care to painstakingly examine the pros and cons of a statement *Lecturers at the University of Ilorin. 94 closely, analyse the data consequent upon or leading to that statement before setting it down for public scrutiny. The interested reader is most certainly likely to be carried away by the sheer number of notes, footnotes, quotations, and tabulations, all being relevant. The title of the book may however be considered an understatement of the author's preoccupations. Even though the author claims to set out to deal with "some of the organizational and sociolinguistic aspects of French language aquisition and use in Africa" (Preface p. 1), there is compelling evidence that he has done much more. Consider his standpoint on some pedagogical proposals (including his) as contained for example on pages 36, 44 and 73. On the basis of the fact that accent is an important incontrovertible index of what constitutes a difference between Central French and African French, if the latter is assumed to exist, the chapter on the teaching of French pronunciation in Africa (Chapter 5) is crucial to the assessment of the extent to which the African student of French has deviated from metropolitan French. As the author reminds us, segmental as well as suprasegmental parameters are the bedrock of "the beauty and harmony of French" (p. 98). According to the author, French of Africa would he satisfactorily said to exist if, out of the multitude of ‘ethnic speech habits' of the African learners of French, it is possible to extract what could be described as a common core. This core would be identified in terms of, not just the lexicon but also the sociolinguistic environment that shapes and conditions speech generally. Now, available evidence of the varieties of such ethnic habits, as the author notes, is still fragmentary, if not partial. This is probably why the book limits compelling references to West and North Africa, (to the exclusion of say East Africa). Yet it would be most interesting to know what form French language teaching assumes in countries like Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia and even Mozambique to mention but a few, for a near-comprehensive picture of the problem to emerge. While the absence from the book of such corroborative evidence (apart from the sketch credited to Makouta-Mboukou) is, to be sure, the result of the limits of documents available to the author, it does mean that the provision of such evidence represents an urgent task for French language researchers in Africa. It is indeed when such gaps have heen filled that Kwofie's laudable attempt to posit a "set of universals" for French language teaching in Africa could properly assume the status of scientific generalisation. Language is considered by sociolinguists both as an expression of shared experience and as a tool for manifesting the culture of the owners/users of the language i.e. a tool for relating to the environment in which the experience is rooted. It is in this sense, I think, that Emile Durkheim's definition of language as "social fact" could be understood. Consequently, the teaching of French in Africa should, in my opinion, integrate the civilisation, culture 95 and social history of the language. This, in many parts of Africa, is being done. If the concern in French Language Teaching in Africa is the content of the teaching package, and the modalities for conveying this package to the African, it might be appropriate to include some observations on the role and status of culture and civilisation of France (commonly called French Civilisation) in the package. Several important statements have been made by the author in respect of the role of linguistics in the whole business of language teaching (Vide p. 23-30). Perhaps the most significant of them bears on the limits of the discipline called linguistics. Like many before him (and he acknowledges almost all of them) Kwofie rightly calls for caution in the manner in which we seek deliverance from linguistics (applied or not) in the matter of language teaching, and worse still, language learning. Says he "French language instruction in Africa,... would be at least twenty years behind where it is today were the doctrine of applied linguistics adhered to rigorously" (p. 37). One cannot agree with him more. Second is the question of teacher's expectation from the learner in terms of competence. The point seems to me well made that it is Utopian to expect absolute mastery of the French language from the African, since, as observed by Martinet, it is practically impossible for the native speaker of French to attain such mastery. This statement which, as the author correctly remarks, is a confirmation of Martinet's position in Le Franqais Sans Ford, (1969), raises for the sociolinguist the question -of how much of the language we should expect from the African learner, and of knowing whether an impressive integration of local resources into Central French may still not affect our assessment of his competence as long as this does not drastically interfere with syntax, and on condition that the learner possesses parallel patterns available in Central French, making diglossic use of the two sets of patterns. This question, like several others raised in the book, is an issue in applied linguistics; hence a further justification of the sub-title. French Language Teaching in Africa is a good reference book in the sense that it has a very rich bibliography. It should appeal to all students of French language pedagogy and should rightly whet the appetite of researchers in the growing field of communicative competence in French as a foreign language. An important way of getting the message of this book across the continent is by providing immediately a French version of it. In a recent article entitled: "Le francais dans tous ses etats" in "LeFrangais dans le Monde" Août-Septembre 1986 (pp.24-5), Louis-Jean Calvet reminds us of Emile Coenouvrier's observation, that French in relation to other languages cannot but keep a status of 'co-habitation'. African languages, including English as official language in Africa, are members of the party involved in this 'cohabitation'. Consequently, French language teaching in Africa 96 cannot but take into account what could he described as the co-. habitation factor. As the evolution of the French language cannot be divorced from its trappings in Africa, so does its teaching in Africa rest upon our awareness of the evolution of teaching methods generally. If today, therefore, we speak of ecclectic method, tomorrow structuro-global method or the 'methode de grands groupes' may replace or be included in that method. One wonders in fact if that tomorrow has not come. The signs are perhaps better captured by Henri Boyer and Michael Rivers in their Introduction a la didac-tique du franqais, lanqiie etrangire (Cle international, 1979). 97