Exploring positioning, purpose and power through

advertisement

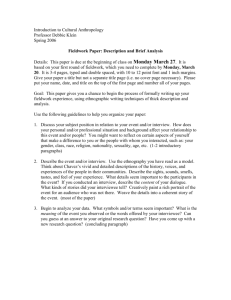

Exploring positioning, purpose and power through pictures, poetry and progress charts: An introduction to some different ways of working with fieldwork data. Ann-Marie Bathmaker, Faculty of Education, UWE Bristol Paper presented at the University of Sheffield School of Education Doctor of Education Programme (Dublin) May 2007 Introduction This presentation is about different ways of working with fieldwork data that we have been using in the FurtherHigher Project. My aim is to offer some of our ideas for working with and presenting data, and to discuss what we are hoping to achieve by trying out different approaches. I will start with a brief introduction to the FurtherHigher Project. I will then explain the origins of the ideas that are presented here, and discuss what purposes they might serve in considering positioning, purpose and power in the context of widening participation in higher education. The main part of the presentation is about the ideas themselves, and how we are using them in the FurtherHigher Project. There are three people in the project team who were responsible for the original ideas and for their development, and on whose work this paper is based: Cate Goodlad, Will Thomas and Val Thompson. The FurtherHigher Project The FurtherHigher project is a two-year study, which is investigating widening participation in undergraduate education in England. It focuses on the impact of the division between further and higher education into two sectors on The work reported in this paper forms part of the FurtherHigher Project. The FurtherHigher Project is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (Award Reference RES-139-25-0245) and is part of the ESRC’s Teaching and Learning Research Programme. strategies to widen participation. The project has used both qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate the changing shape and experience of HE in England. One strand of the project is concerned with students’ experience of transition between different levels of study. This part of the study seeks to gain insights into what it means to move into and between different levels of higher education, and the meanings given to higher education transitions, by students studying in what the project refers to as ‘dual sector’ institutions, that is, institutions which offer both further education and higher education. The aim is to develop understandings of students’ identity formation, as they negotiate boundary crossings between different levels of study, and to explore how the development of learning career and identity in such contexts may affect and contribute to participation in higher education. The fieldwork for this part of the project explores student transitions from FE to HE levels of study, and from short cycle (Foundation degree, HND) to BA/BSc level of study. Four dual sector institutions, two of which are officially within the English Learning and Skills sector, and two in the higher education sector, are involved in the fieldwork. Students who remain within the same institution, and students who transfer to other institutions are included in the fieldwork. In each institution we are following between five and ten students at each of these two levels for one year. The fieldwork has included interviews with students, tutors and institutional managers, documentary analysis, and the collection of fieldwork observation records. Friday afternoon syndrome The fieldwork team consists of five university-based researchers and four research associates, one based in each of the case study institutions. I have learned from working as part of the fieldwork team that several of us experience ‘Friday afternoon syndrome’. In practice, this is not actually Friday afternoon for everyone, but it goes like this: I’ve been working really hard, I’ve been sorting data, I’ve been thinking about the project, I think I’ll just do a bit of browsing. 2 Browsing can mean web surfing, it can mean browsing library shelves beyond the precise book you came looking for, it can mean doodling on paper, it can mean seeing what charts Excel will produce and whether bars look nicer in blue or pink. I call this Friday afternoon syndrome, because, the emails that arrive late on Friday afternoon from one team member in particular, start: ‘It’s Friday afternoon….’ These are not the emails where you press delete, these are the emails where you read on. The results of these activities, where work dissolves into play, and play merges into work, are the examples which are presented below. What started off as ideas that we played around with, are now becoming tools for analyzing and re-presenting the data from the project, and are helping us with our thinking about what we are doing and what we are finding. They are helping us to discuss with students and staff who are contributing to the fieldwork, as well as with others, what we are finding. They are also offering a means of presenting the data in interesting ways that may help us to be both critical and reflexive in our re-presentations. Exploring positioning, purpose and power The FurtherHigher Project asks the question: What is the impact of the division between further and higher education on strategies to widen participation in undergraduate education in England? One of the obvious impacts of this division is that it contributes to the stratification of higher education, and it adds further layers to that stratification. The inevitability, indeed the necessity, of stratification in a mass system of higher education, was argued by Trow as early as 1973 (Trow, 1973). Trow acknowledged then, and in later work (2000), that a stratified system also means a differentiated system, but the term ‘differentiation’ encompasses both positive and negative aspects of work to widen participation in education. The use of the term for both can tend to obscure one or the other. Thus to give an example form a school context, differentiation has been demanded of school teachers in England for some years. Here, it is used to 3 refer to the way that teachers should ensure that what they do responds to the different needs of pupils in their classes, so that pupils across the achievement range are given opportunities to learn, make progress and to succeed. This conceptualization of differentiation could however also mean that pupils are taught in different classes, and taught different subject matter in those classes. In the context of higher education this latter version of differentiation can be seen in different forms of higher education such as Foundation Degrees, and different locations for higher education such as further education colleges and the workplace. Already, provision such as this opens up less positive implications for differentiation within a stratified system of higher education. Clancy’s work (for example, Clancy 2006) raises issues concerning equity in relation to the stratification of higher education. A stratified system is not an equal system – each layer is not equally valued, neither in the field of higher education, nor in society more widely. Moreover, getting rid of sectoral divisions, such as happened with the unification of English higher education following the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act, when former Polytechnics gained university status, does not get rid of stratification, it simply obscures it, or names it differently. (Former polytechnics continue to be known as ‘new’ or post-1992 universities.) One of the things that we have learned in the FurtherHigher Project is how aware staff and students in different institutions are of the stratified nature of HE. We have found evidence of various processes of ‘positioning’, whereby institutions try to define their place within the system, teachers try to define what sorts of students different courses in different places are for, and students try to work out if there is a place for them in higher education, and if so, where they should position themselves (see Bathmaker, 2006). We are grappling therefore with the implications of stratification and differentiation for widening participation – the uneasy trade-offs between more opportunities, including opportunities that are more attractive to ‘nontraditional’ students, but at the same time, more opportunities that may carry less value as potential economic, cultural or social capital. 4 As the above discussion indicates, our question about the impact of the division between further and higher education on strategies to widen participation in undergraduate education in England lead into questions about notions of justice and equity. Widening participation in higher education is ostensibly rooted in concerns for justice and equity. There are however, different ways in which such concerns may be understood (discussed in detail in Gewirtz and Cribb (2002), Gewirtz (2000) and House (2005)). Following their analysis, widening participation policy might be seen as part of a politics of redistribution. Here the concern is not just with increasing what is available, that is, the amount of education, but with the distribution of higher education amongst different groups or fractions of society. What such an approach to equity and justice does not necessarily do is to address issues of democratic participation, that is, the nature of participation, and the opportunity for stakeholders, especially those who have traditionally been excluded, to have an effective voice in defining their own needs and negotiating benefits, what Gewirtz and Cribb (2002) refer to as participative justice. Nor does it necessarily focus on respect for and recognition of cultural identity, as part of a politics of recognition (Gewirtz and Cribb, 2002). Whilst these ways of distinguishing different understandings of justice and equity are useful, more challenging is Gewirtz and Cribb’s outline of plural models of social justice, shown in table 1. The features of a plural model of justice act as a strong challenge to arguments that one, best version of higher education is what should be available to all, and raise all sorts of issues about what higher education might look like, whether differentiation can be equitable and what that would mean. 5 Table 1: Six dimensions of pluralism in models of social justice Source: Gewirtz and Cribb, 2002, p.501 What do alternative forms of working with data do? In carrying out research into widening participation for the FurtherHigher Project these issues are not straightforward, nor easy to get a hold on in relation to the data we have collected. They turn our apparently straightforward question into a complex, multi-faceted problem which will not allow for easy answers. Friday afternoon syndrome is part of our attempts, individually and collectively, to pursue these sorts of concerns further in the fieldwork and in the data we have collected. It moves the pictures, poetry and progress charts that I go on to present next, from games and ‘Friday afternoon colouring in activities’, to part of a more critical project, which encourages us to explore our data in different ways, and ultimately to make connections between power, positioning and purpose, and to consider both macro structures and micro opportunities for agency. These different ways of working with data are therefore not just ways of analysing and presenting data, but act as forms of knowledge production, and 6 work as vivid reminders to us as researchers that we construct and produce knowledge, we do not just report neutrally on knowledge we have collected. Whilst the nature of research knowledge as something that is not objective, neutral, and out there to be gathered, sorted and reported is not new, it is often difficult to grapple with data, arguments and ideas, objectivity and subjectivity, in the effort to turn a mass of fieldwork data into a coherent research report. The different approaches we have been trying out have forced us to think through such issues, in terms of what we choose to present, how we choose to present it and what effect a particular form of presentation has – what stories it allows us to tell. I want to conclude by acknowledging that what I am saying here is not new. Writing this paper led me back to rereading C. Wright Mills book The Sociological Imagination, published in 1959 (Wright Mills, 1959), and I want to conclude with some comments from his end piece about the craft of the sociologist, which provide resonances with the experience of the team working on the FurtherHigher Project, and which are taken from a chapter which provides an insight into how he went about doing his work and how he set about defining the work that he was doing. The sociological imagination The most admirable thinkers within the scholarly community you have chosen to join do not split their work from their lives. (215) To unleash the imagination he recommends: Rearrange the file of ideas, papers etc that you have collected Be playful with phrases and words with which issues are defined, for example look up synonyms, and pursue words to their roots Set up a new classification: charts, tables, and diagrams of a qualitative sort are not only ways to display work already done; they are very often genuine tools of production. (234) How you go about arranging materials for presentation always affects the content of your work (237). 7 The point of cultivating a sociological imagination Know that many personal troubles cannot be solved merely as troubles, but must be understood in terms of public issues – and in terms of the problems of history-making. Know that the human meaning of public issues must be revealed by relating them to personal troubles – and to the problems of the individual life. (248) The sociological imagination has its chance to make a difference in the quality of human life in our time. (248) Every picture tells a story: of pictures, poetry and progress charts The following section shows the following forms of analysis and representation, courtesy of Val Thompson, Will Thomas and Cate Goodlad. 1 Tables 2 Maps showing where students live in relation to where they study 3 Pictorial diagrams showing ‘learning careers’ of students 4 Photos of learning spaces in a college 5 Student timetables 6 Waterlogic diagrams showing analyses of key interview themes 7 Tag clouds showing pictorial representations of key interview themes 8 A Stick Verse about data analysis 8 Tables and charts Table 1: AVCE Health and Social Care sample at Northgreen College Pseudonym Hannah Sarah Jessica Robin Ria Age 18 18 18 18 18 Gender Female Female Female Female Female Ethnicity White British White British White British Mixed White and Black Caribbean Asian British –Pakistani Table 2: Higher National Diploma sample at Northgreen College Pseudonym Karen Elizabeth Ruth Debbie Christine Margaret Jacqueline Peter Age 23 26 27 38 46 64 33 21 Gender Female Female Female Female Female Female Female Male Ethnicity White British White British White British White British White British White British Black British -Caribbean White British 9 Google Earth maps Will Thomas Maps can be used to show aspects of ‘space and ‘place’ very clearly. Here, they are used to show where students live in relation to where they study. 1 2 3 4 5 How to Create Placemarks in Google Earth 1. Enter the postcode of the place you would like to mark, and click on the magnifying glass [The view will change to show the place you have selected] 2. Click on the pushpin icon [A box will appear] 3. Enter a name for the placemark 4. If you would like to change the colour or style of the placemark click on the “Style, Colour” tab 5. Enter a description of the placemark if you wish 6. Click OK, and then start again from 1 10 Location of case study and other Further Education Colleges Home locations of National Diploma Business Students from East Heath College 11 Home locations of National Diploma Sports Students from East Heath College Home locations of Foundation Degree Early Years Students from East Heath College 12 Pictorial representations of learning careers http://www.inspiration.com/techsupport/index.cfm Val Thompson The computer programme used to create the pathways diagrams is called Inspiration. It is a programme which many universities offer to students who have been identified as dyslexic as a potentially effective way of creating mind maps. I have worked with students who find it a very useful tool as it is a quick and flexible way to put words onto a page and to show relationships between ideas or facts. Added to this, there are the options of colour, graphics and audio which can be used to enhance the text and which can act as memory triggers. I chose to develop some of the data which has been generated by the Furtherhigher Project into diagrams which show student participant details and journeys into Higher Education because I did not want to ‘contain’ these in a chart or table as has been done in much other work which includes participant educational biographies. For me, the diagrams I have used are more organic in shape and they reflect, more accurately than the boxes of tables or charts, the meandering journeys which some student participants make on their way to or back into HE. The use of colour also allows relationships between certain areas to be highlighted and additional graphics can be added to illustrate individual or idiosyncratic aspects of these journeys. The diagrams also have the potential to use audio thumbnails which might add impact and interest to presentations. When used to illustrate groups of individuals, I believe that they allow the reader to see differences more effectively than a table, where the boxes drawn are all made from the same dimensions. These diagrams vary in size. Where they are used to show individual details, they act as a graphical reference to the narratives which can be set in parallel onto the page (not shown here). In constructing these diagrams I have been attempting to reconcile my conflicting thoughts about the ways that research represents participants. On the one hand I acknowledge the need for providing basic information for the reader such as gender or age. On the other hand however, I feel that some devices allow participants to disappear or become ‘othered’ in some way through the paratextual devices chosen. What I have done with these diagrams is to try to find a paratextual form which can run alongside and summarise the narrative approach which I prefer to utilize. 13 HE HE ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME FULL TI ME EMPLOYMENT ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME HE ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME HE ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME HE ACADEMIC BRIDGI NG PROGRAMME FE PART TI ME PART TIME EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYER TRAI NING HE WORK BASED LEARNI NG FE ASSESSMENT PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FE COLLEGE PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FE COLLEGE WORK EXPEREINCE PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FE COLLEGE FE COLLEGE FE COLLEGE HOME AND FAMILY FULL TI ME EMPLOYMENT RETURN TO SCHOOL NO QUALIFICATI ONS PART TIME EMPLOYMENT SCHOOL 6TH FORM A LEVELS FE COLLEGE GCSE'S AT SCHOOL GCSE AT SCHOOL Lizzie Diana College A Pathways to higher education CULINARY ARTS MANAGEMENT GROUP 1: ACADEMIC BRIDGING PROGRAMME SCHOOL 6TH FORM A/S LEVEL GCSE AT SCHOOL James 14 FULL TI ME EMPLOYMENT GCSE AT SCHOOL GCSE AT SCHOOL Matt Paul NO QUALIFICATI ONS AT SCHOOL Lilly HE HE HE HE HE PART TIME EMPLOYMENT PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME HE PART TIME FE PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FULL TIME EMPLOYMENT PART TIME FE PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FULL TIME EMPLOYMENT PART TIME EMPLOYMENT FE COLLEGE A/S LEVELS AT 6TH FORM COLLEGE SCHOOL 6TH FORM A LEVELS A LEVELS AT SIXTH FORM COLLEGE FE COLLEGE GCSE'S AT SCHOOL GCSE'S AT SCHOOL GCSE'S AT SCHOOL GCSE'S AT SCHOOL CSE'S AT SCHOOL Gerrard Elizabeth College A Pathways to higher education Culinary Arts Management GROUP 2: PRACTICAL BRIDGING PROGRAMME Geoff 15 Skittles Jen ? Louise Photographs Teaching room at Daiston Campus site of Northgreen Federal College Wall display in teaching room at Daiston Campus site of Northgreen Federal College College notice at Tultry College site of Northgreen Federal College 16 AX011: Timetable for the week in year 1 of Social Work at University (constructed 4 December 2006, interview 2) Monday 9-15.00 Paid (employment employment hours) (1) Agency work: Teaching 10-16.00 assistant in (study special hours) needs, anywhere in the city Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Paid employment Agency work: Teaching assistant in special needs, anywhere in the city University University lectures and lectures seminars and seminars Teaching for 1 Teaching module, for 1 lasting all module, day lasting all day University Watches library for TV (East 3 hours Enders) [employment [employment is related to is related to area of HE area of HE study] study] Evening Paid employment Agency work: Teaching assistant in special needs, anywhere in the city Meets friends for a chat Does university work [employment is related to area of HE study] Study for university, caring for mother (1) Employment: was key worker for a boy with SEN. This was too big a commitment when started at university and has switched to agency work. Both previous and current employment related to her area of study. (2) Highlighted in yellow: timetabled study at university 17 AY1003: Timetable for the week in year 3 (final year) of BSc Sports Therapy (constructed 13 November 2006, interview 2) Monday 9-11 11-13.00 13.00-14.00 Lecture Entrepreneurial Studies Seminar Entrepreneurial Studies Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Lecture NO CLASSES Professionalism NO CLASSES and ethics Time used for work on dissertation and assignments Time used for work on dissertation and assignments Goes to gym Goes to gym 14.00-16.00 16.00-18.00 17.30-19.00 Lecture Diagnostics and management theory Personal: athletics training at nearby University Practical Diagnostics and management (seeing clients, carrying out diagnosis and treatment) Supervised by course tutor Saturday Sunday 2 hours study 2 hours study (more or less depending on how much completed during week) (more or less depending on how much completed during week) Personal: athletics training at nearby University No regular paid employment, but works at gym in home city on occasional basis about 2 weekends a month Highlighted in yellow: timetabled study at university 18 Water Logic Edward De Bono (1993) Waterlogic, London:Penguin Books. Cate Goodlad Cate Goodlad has been using ‘Water Logic’ to analyse interview data and to take her preliminary analysis back to interviewees. Water logic is a practical thinking tool where you create ‘flowscapes’ that allow you to see at a glance the important points and relationships. These are very easy to construct and not very time consuming. De Bono suggests that we have been taught to think in terms of traditional ‘rock logic’. This focuses on ‘what is’; facts and objectivity. However, most of the time we use perception which does not follow ‘rock logic’ at all. Perception is based on water logic – it flows, is not definite or hard edged but can adapt to containers. Rather than being based on ‘what is’, water logic is based on ‘what this leads to’. Example from De Bono: A woman takes a faulty kettle to a department store and asks for a replacement. The sales assistant knows that the kettle could not have been bought there as they do not stock that brand but the assistant replaces the kettle with a new one. On the basis of rock logic this would seem absurd but with water logic this makes sense. The woman is so pleased with the service she received that she becomes a regular customer and spends much more money in the store. What you do Create a steam of consciousness list of the key points which might be features, ideas, factors that occur to you. This should not be laboured over as it may distort the final ‘flowscape’. Next, label each item on the list A, B, C etc. The next step is the most important and involves the flow. Again it is important not to try to predict the outcome and distort the flow. Taking each 19 item on the list ask yourself ‘where does this lead to?’ It is important not to think in terms of cause and effect but what comes next. All items on the list lead to another item on the list. Next plot out the letters into a flowscape. It is easiest to start with the most frequent destination letter. Collection points are key factors as are loops which form stable perceptions. Example of Lorraine A radiotherapy D B young child E C localness B D travel E E better herself A F boredom D G admin jobs D H little family support D C B E H F A D G 20 localness young child to better herself little family support Boredom Radiotherapy travel Admin jobs Key collection points are E (better herself) and D (travel) – these are her main drivers. These two are linked by A (radiotherapy) which forms a stable perception by the loop. So she will better herself through radiotherapy which will lead to travel which in turn will make her a better person. Some problems It is difficult not to pre-empt the outcome of the flowscape and takes a bit of time to think about how the person perceives the situation, rather that yourself. I’ve also found that some of the things noted down in my stream of consciousness list do not appear to ‘lead’ easily to another in the list. I have had to decide whether I needed to add something else (and then what would this lead to on the list) or to delete that thing in the first place. I have found it a useful tool to explore people’s perceptions and participants seemed to enjoy the analysis. It therefore provides a good talking point. 21 Waterlogic Flow Sally A ‘normal’ route B B ‘better’ job A C Heavy workload D D harder K E modules J F placements J G lack of money K H independent learning N I different to college H J Assessments N K Pressure H L Part-time work K M student identity Higher-status H N first-class degree B 22 Sally Flow Diagram 1 Heavy workload Harder Part-time work Lack of money Pressure Different to college Student identity Higher status Independent Learning Placements Modules Assessments First-class degree ‘Better’ job 23 ‘Normal’ route The stream of consciousness list is derived from two interviews with Sally, one at the end of her Access to HE course and the other a few weeks into her BA in Physiotherapy course. Sally already has a BA in Politics for which she achieved an upper second class degree but found it difficult to get a job that she enjoyed so has returned to retrain at the age of 27. When producing the stream of consciousness list, the question in mind was ‘what does HE mean to Sally?’ As she has previous experience of HE, she had some idea what to expect although this time she is living with her parents rather than being in halls of residence. She talks of how university is different to college in that you have to be a more independent learner and that when she was at college she didn’t always tell people that she was studying as it didn’t have the same status as studying at university. She associates HE with work modules, placements and assessments which she is hoping will lead to a first-class degree this time round. Sally has experienced a heavy workload which is much harder leading to a great deal of pressure. This is compounded by lack of money and working part-time. She seems to accept that this is not only what HE looks like but also how it should be as it will lead to a ‘better’ job. At the end of the third interview the flow diagram was presented back to Sally for her comments. She agreed that this was a fairly accurate description of how she sees HE and commented that it was interesting the way that pressure had become a collector point. She then revealed that she has recently seen a councillor in the university to help her cope with the stress, something that she did not reveal in the normal course of the interview. We discussed the effect of this pressure which may be as much down to her own high standards and the wish to attain a first-class degree. We decided that the flow diagram worked better by rearranging the flow to acknowledge the pressure that she is putting on herself and created a new flow diagram. 24 Sally Flow Diagram 2 Placements Modules Student identity Higher status Assessments Different to college Independent Learning First-class degree Heavy workload Part-time work Harder Lack of money Pressure ‘Better’ job 25 ‘Normal’ route Tag clouds http://www.tagcrowd.com/ Will Thomas Tag clouds can be used to analyse key themes and issues coming out of interview data. Tagclouds are basically a visualisation of word frequency, which can be generated using the Tagcrowd website. The examples below show what tag clouds are and how they might be used for analysing and representing data. Example 1: The relative importance of different themes coming out of interview data adventure exams experience helped tutor teacher school college ucas mum coursework money attitude atmosphere university information told degree employment hard dad study friends In example 1 (which is fictitious) the use of different colours links terms together as forming part of one theme. The size of the word is used to show a measure of frequency. In this example tutor, teacher, mum, dad and friends all appear in orange, and form part of a theme concerning social networks of influence on students’ decision-making. The word ‘tutor’ is the largest in this set, and indicates that this term occurred most often. Example 2: Positive and Negative Influences on decisions about whether to enter HE confidence career accommodation T&L tutor family location friends wages fees type of institution experience influence bursaries grades coursework exams 26 S&P In example 2 (which is fictitious), colours (green and red) have been used to represent whether the word or influence is deemed to be ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, in terms of whether this factor promotes or discourages progression. The size of the word represents the importance of this factor, as determined through contextual analysis of the interview transcripts. It would be possible for the same term to appear in both colours, to indicate that it represents both a ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ factor. Analysis could either take the form of analysing the frequency with which the terms occur in the transcript, or could be used following initial analysis, to count the number of references to a particular theme in the transcripts. In this case one reference might consist of several sentences, where the term (family for example) occurs several times. Tag clouds from transcripts of students all following one course are shown below. CX3002 CX3003 27 CX3004 CX3005 CX3006 28 Poetry Val Thompson The poem ‘Gerrard’ is an attempt at highlighting the ‘disappearing’ that was referred to earlier (see Pictorial representations) through starkly listing the many stages which are often a feature of the research process. Through these stages, it seems to me, something of the person who is a participant in the research is lost. The Stick Verse form is a visually powerful way of illustrating how an individual might vanish. It is short; only thirty two words long and begins with very personal, individual and subjective detail. It then moves rapidly on to the ostensibly more objective processes, the ones which use very scientific sounding terms, which lead to the disappearing. The poem also pays attention to the rhythm and rhyme of the words and word order which make it work at an aesthetic level. The use of poetry as a form of representation in educational research is supported by the work of Cahnmann (2003) who, whilst acknowledging the view that not all educational researchers can write quality poetry, is encouraging and argues that educational researchers should and can acquire the skills and techniques utilised by arts based researchers because: ‘Through poetic craft and practice, we can surprise both ourselves and our audiences with new possibilities. Using elements of poetry in our data collection, analysis and write-up has the potential to make our thinking clearer, fresher and more accessible and to render the richness and complexity of the observed world’ (Cahnmann, 2003 p.37). Although she describes poetry as ‘a risky business’ (p.31) she sees the risk as one worth taking and echoing Laurel Richardson (2002) sees it as a means through which larger and more diverse audiences can be exposed to, and have access to the outcomes of educational research. The poem ‘Gerrard’ has already been presented to a wider audience through my association with a poetry writing group at a poetry café where its creation and craft as well as its meanings and purpose have been the subject of lively discussion. 29 Gerrard Gerrard wiry sharp young son brother scoucer fresher pleasure to talk to interview digitize download attach to an email transcribe anonymize import into ATLAS ti code explode analyse theorize publish Gerrard dog-eared disappeared. Val Thompson, March 2007 30 References Apple, M. (1996) Power, Meaning and Identity: Critical Sociology of Education in the United States, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 17, 2, pp.125-144. Bourdieu, P. (2000) For a scholarship with commitment, Profession, MLA Journal, USA. Cahnmann, M. (2003) The craft, practice and possibility of poetry in educational research, Educational Researcher, Washington, 32, 3 pp. 29 – 40. Clancy, P. (2006) Structural Features of Higher Education and Second Level Systems and their Relationship to Levels of Participation and Equity. Working Paper, Fulbright New Century Scholar Programme. Gewirtz, S. (2000) Social Justice, New Labour and School Reform IN Lewis, G., Gewirtz, S. and Clarke, J. (eds) Rethinking Social Policy, London: Sage with Open University Press, pp.307-322. Gewirtz, Sharon and Cribb, Alan (2002) Plural Conceptions of Social Justice: Implications for Policy Sociology, Journal of Education Policy, 17, 5, pp.499-509. Hartnett, S.J. and Engels, J.D. (2005) “Aria in time of war”. Investigative Poetry and the Politics of Witnessing IN Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edition, London and Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp.1043-1067. House, E. (2005) Qualitative Evaluation and Changing Social Policy IN Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (eds) Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edition, London and Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp.1069-1081. Lather, P. (1995) Feminist Perspectives on Empowering Research Methodologies IN Holland, J. and Blair, M. with Sheldon, S. (eds) Debates and Issues in Feminist Research and Pedagogy, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters and The Open University, pp.292-307. Mills, C. Wright (1959) The Sociological Imagination, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Richardson, L. (2002) Poetic Representation of Interviews IN Gubrium, J. F. and Holstein, J.A. (ed) Handbook of Interview Research Context and Method Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage. Trow, M. (1973) Problems in the Transition from Elite to Mass Higher Education. Berkeley, CA: Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. Papers related to the FurtherHigher Project include: Bathmaker, A.M. (2006) Positioning themselves: Higher education transitions and ‘dual sector’ institutions. Exploring the nature and meaning of transitions in FE/HE institutions in England. Paper presented at the ESRC TLRP Seminar Series Transitions through the lifecourse at the University of Nottingham on 12-13 October 2006. Bathmaker, A.M. and Thomas, W. (2007) Positioning themselves: An exploration of the nature and meaning of transitions in the context of dual sector FE/HE institutions in England. Paper presented at the International Conference on researching transitions in lifelong learning at the University of Stirling, 22 - 24 June 2007. They are available on the project website at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/furtherhigher/ 31