T

advertisement

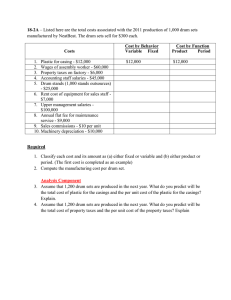

‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation YORUBA DRUM LANGUAGE: A PROBLEM OF INTERPRETATION By BADE AJAYI drum that can know what the drum is saying. The interpretations of what Onibode Lalupon’s drummer says with his drum are a clear proof of this claim. What the drummer a claim to have said with his drum is: INTRODUCTION The Yoruba drum is an example of non verbal channel of 1 communication . It is a highly specialized form of expression. Besides the drum, a Yoruba can communicate through the royal trumpet (Kakaki), the metal gong (Agogo), the hunters' flute (Ekutu) the cymbals (Aro), the beaded gourd (Sekere) land some other musical instruments. When a Yoruba drummer 'talks' with his musical instrument, not every member of the society can understand what he communicates, talkless of interpreting it. This problem of' interpretation forms the main theme of. "Onibode Lalupon", one of Adebayo Faleti poems (see Olatunji, 1982b: 2—5). The summary of Faleti's claim is that nobody can be definite about the meaning intended by the drummer. Sugbon ko seni to mede ayan, Bi eni to mopaa e lowo. Eni to gbomole 1owo 1o le mohun tomole n so. (OIatunji l982a: 5) (a) Mo jeun Ejigbo, Mo jeun Iwo, Mo jeun Onibode Lalupon. I ate Ejigbo's food, I ate Iwo's food, I ate the food of the gatekeeper at Lalupon. which the listeners interpret as: (b) E wenu Imado, E wenu Isin, E wenu Onibode Olupo Look at the mouth of the wart-hog, Look at the mouth of the minnows, Look at the mouth of the gate keeper at Lalupon (Olatunji 1982a:26—28) The drummer's intended meaning is a praise acknowledging the generosity of Onibode Lalupon. But the drummer's detractors inform the gate-keeper that he has been abused by the drummer. The gatekeeper grows annoyed and he decides to But there is no one who knows the language of the drum, Like the man holding the drum stick in his hand It is the man who hold the omole 29 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation punish the drummer. Thus a different inter-of the drum language may cause confusion, quarrel and some other problems between the drummer and the listener (S). If we accept the fact that it is only the drummer that can tell what he says with his drum, our question now is "why is it that people find it difficult, if not impossible to interpret the message of a drum to conform with the communicative intention of the drummer?" It is this question this paper attempts to answer. To start with, let us compare briefly the drum language with that of human language. lower level of structure distinctiveness than the human language per se. A drum is manipulated by man to produce sounds imitating speech tones3. Thus, the message given by the drum is always ambiguous because it is based on tones and rhythm. While a man can speak to express his thought and feeling, to the unmistakable understanding of the listener, a talking drum is manipulated to give what the drummer has in mind but which may not be shared by his listener. A talking drum only "talks" when we beat what to say and how to say it and so is only imitating human speech on a prosodic level The Language of the Drum and the Language of Man The language of the drum is fundamentally different from human speech. Human speech is articulate and the organs involved in the production of sounds include the lips, the teeth, the tongue and the glottis. These speech organs produce the vocal sounds which provide the material for a particular language2. It is important to remember that basically a language is something which is spoken (its codification in writing being secondary) and because it is verbal, human language is less ambiguous than the drum language. Apart from speaking, we can play some other tricks with our vocal cords: we can whisper, or laugh, or use the techniques of calling dogs, fowls, goats all of which cannot be done meaningfully on the drum. On the other hand, the drum beats are not articulate. This means basically that drum sounds have a 30 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation The Musical Role of the Drum Like some other African drums, the Yoruba drum performs both rhythmic and communicative functions. However, the basic role of drums is music performance. The Yoruba drum may create motorresponse from the individual or a group of people finding outlets in dancing, working or fighting. It may also serve as therapy for the troubled minds or the bereaved people and sustaining courage, especially when the hope is lost. Another important musical role of the Yoruba drum is that it may signal danger, give warnings or mobilize people to do some kind of work. In addition, the Yoruba drum such has the dundun and bata are useful tools for commercial advertisements as well, as social and political campaigns. Unlike the other nonverbal modes of human commuication such as gesture, facial expression, eye movements and head nods, the Yoruba drums are socially employed to entertain, inform and instruct members of the commnunity. Aro (cymbals) players4 have, to enable them interpret simultaneously what the drummers beat on their drums. These players have close contact with the drummers. The Problem of Intended Meaning The interpret the drum language, certain things have to be done. (i) One who interprets must have a common semantic dialogue with the drummer over a conventional meaning attributed to the drummer. In other word, both the drummer and he who is to decipher the drummer's message must have the same semantic universe which thrives on conventional usage. It is this advantage that the Sekere (beaded gourd) and Akekoo: (ii) It is possible that the communication pact is clear as it is the case when singers are the initiators while the drummer is simply an amplifier. At the 1988 Yoruba Week Celebration' at the University of Ilorin for instance, students sang in honour of Professor Awobuluyi and Professor Olajubu and the drummer participated in the scheme as follows: Akekoo: Talo p'awa o ni baba? Kai a ni baba. Awobuluyi baba wa. Kai a ni baba. Ohun llu: Dan dan dandan dan dan dandan? Dandan dan dan dandan. Dandandandandan dandan dan Dandan dan dan dandan. Ta 1o p’awa o ni baba? Kai a ni baba Olajubu. baba wa. Kai a ni baba. Ohun Ilu: Dan dan dandan dandan dandan? Dandan dan dan dandan, Dan dandandandandan dan, Dandan dan dan 31 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation Students: Who says we do not have a father? Surely we have a father, Awobuloyi (is) our father. Surely we have a father. Drum Language: (Re-echoed Students' song) Students: Who says we do not have a father? Surely we have a father, Olajubu (is) our father, Surely we have a father. perhaps the trumpet or horn blowers with their musical instruments. Also the warleaders do not have problems in undemanding and acting to the praises and words of encouragement, drummed at the battle fields. lt is the preexisting semantic pact that prevents ambiguity in the above examples. the Drum (Re-echoed the Language: Students' song) With the above technique, the listeners or the audience would have no problem of understanding what the drum says. Thus, the communication pact is clear when people are the initiators of a particular song. When Ayanyemi Atokowagbowonle, a popular drummer in Ibadan discussed elsewhere (Ajayi 1988} communicates with his drum, the Sekere players who are used to what the drum says effortlessly interpret the message for the listeners to understand and appreciate. In Yorubaland every public figure like the Oba, the Baale and some traditional chiefs have their own special drummers.5 These are expert drummers who possess the mastery of, the accepted vocabulary of the drum language and the Oriki of particular rulers. The drummers perform from day to day such chat the rulers and their people get familiar with what the drummers and Basically, it is possible for a conventional coming to be attributed to a stretch of sounds by the drummer for communicating purposes i.e. if only there is a pre-existing optic pact Without the pact, it is highly useful that everybody except the drummer self will give the intended meaning, is worthy of note that in any complicated them such as communication by means of drum, breakdowns are possible. When there is a broken wire in an electrical 32 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation 5 O kawe ni la’san, ko mo doo doo 6 Bi ko ba le wa mo, dide soro soro 7 O kankuta mole afi gbongbon 8 O si gba mi leti, afi gbosa gbosa 9 O fo jade nile, afi foro foro 10 Magaji olowo iwo lagba lgba 11 Won si de mi lade, ofi pira pira 12 O si mo mi loju afi moin moin 7 circuit power failure may result, Likewise, if there to pact in musical communication it can result in failure to accomplish the purpose of drummer's message. Ambiguity and Narrowness of Means A human language, syrnbols and combinations of sounds are used for effective communication. But a drummer uses only tones and rhythm, a narrow means to communicate his thought. This makes it difficult for many people to-interpret the rescure message of a drum. Of course, in any medium of communication where a limited number of people can understand, there is surely to be ambiguity or multiplicity of clings. Even in human language where a limited number cannot be understood properly by /listeners, communication cannot be said be taking place, how much less of a irrogate language like that of the Yoruba drum. In one of its Yoruba programmes “ARIYA", the Radio Kwara of Nigeria read the various interpretations people gave to is of the drumming patterns; This problem of ambiguity in1 the interpretation of drum language is also stressed by Opadotun (1986) when he gives seven possible interpretations to the signature tune "This is the Nigerian Broadcasting Service" on the Western -Nigeria Radio Corporation; Ibadan. The question of ambiguity is further demonstrated when I beat on my drum twelve different thoughts including; Dan dan dan dan dan dan dandan, Dan dan dan dan dan dan dan dan Meaning: "Sagari wole ekeji, awa o se ti baba mo" (Sagari wins the second time, we are no more in support of the father (Awolowo))" Dan dan dan dan dan dan Dan dan dan dan dan dan for a class of 40 B.Ed students on part-time programme at the University of Bonn to interpret Thirty of these students (from Qyo, Kwara, Ondo and Ogun States) give eight That accompanied the song of Ayinde Barrister (a popular Nigerian musician). Here are a few of the interpretations given (in Yoruba): (a) 1 Fadeyi Olori, afi suke suke6 2 Won rin bi olola, afi teki teki 3 Ki Ia 'n ronu fun,awa agbe 4 O dun mo mi, afi yunga yunga 33 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation interpretations is wrong. Each interpreter gives the meaning us the drum beat sounds to him. To oar mind, all the interpretations are valid and constitute part of the total meaning of the utterances. (See Appendix 'B' for, an outcome of the test conducted). Although the wording might be different, each of the interpretations (in a and b) is based on the tonal patterns of the words that are transmitted and the Yoruba talking dram (especially the Dundun) are constructed in such a way that they can produce the three level tones of high, mid and low. Besides the three level tones, the Yoruba talking drums are capable of producing a number of quick glides, falling or rising among the three tones. When a man pronounces a word like Adewale, every Yoruba listener has no problem in understanding that the speaker refers to the name of a person. He has, used the combination of vowels, consonants and tones to produce the intended meaning. But if a drummer attempts to call the same name with his drum8, using only the different meanings while the remaining ten students could not interpret the code. The various interpretations given for the above drum language are: (b) 1 Sagari wole ekeji,emi a se t'Awo mo, 2 Sagari wole ekeji, awa o se ti baba mo, 3 Sagari wole ekeji, awa o jampata mo, 4 Sagari wole ekeji, oun Et’Omololu, 5 Sagari wole ekeji, awa o somo Awo mo, 6.Sagari ekeji, awa o seDemo mo, 7 Sagari wole ekeji, awa a gba ti baba mo, 8 Sagari wole ekeji, ko lee fara're se. Out of these interpretations only one (No. 2) coincidentally agrees with what I have in mind. However, we are not saying that any of the above 34 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation tones and; rhythm, there is bound to be a number of interpretive possibilities to what he beats on his drum. For instance, Adewale could sound like, some other Yoruba names such as Akintunde, Adebisi, Akintola Onifade, Mojiso1a, Ademo1a all of which have the same number of syllables and bear the same tones. With the drum we encode but we decode with human language and that is why we have problem in interpreting drum language. The listeners may not have any difficulty in understanding human languages but only a few can group the message a drum communicates. The diagram below illustrates what we are trying to say. Conclusion In the foregoing, we Have tried to see how the meaning ascribable to the drum beat could trigger off two possible interpretation one of intended meaning and the other of unintended meaning. The question of intended meaning is crucial to the ability to .decipher the message of the drummer. We have only seen that everybody who is proficient in Yoruba language could give the drum tones some kind of meaning which may or may not cohere with the intended meaning of the drummer. The test conducted for the study justifies this. To interpret the language of the drum to conform with the communicative intention of the drummer, a pre-existing familiarity with a conventional pattern of meaning is indispensible. Where it does not it is possible that the preexisting conventional pattern of meaning is not shown by the decoder and the drummer. : Notes 1 Some aspects of the non-verbal modes of human communication include gestures and other kinetic behaviours such as facial expression, eye movements, head nods and body posture. Unless the interpreter or decoder has a pre-knowledge of what the drummer is going to say with his drum, there is bound to be ambiguity in the message of the drummer9. This is so because the drummer has only imitated the speech tones (pitches). No doubt, the question of Faleti's claim hinges squarely upon the intended meaning. Before his claim can be true it must be predicated on the fact that the means of conveying meaning is severely narrow which further inhibits the question of meaning because the narrowness of the channel of communication gives room for multiplicity of meanings. 2 For detail on the production of speech, see Barber (1975: 2- 4). 3 See Ajayi's 'The Training of Yoruba Talking Drummers" forthcoming in ALORE Vol. 2 techniques of playing drums. Sekere and Aro are the two popular accompaniments in 4 35 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation Dundun music in most parts of Yorubaland. Ayanlowo, P.A. Language of the Drum among the Yoruba People, Long Essay, Depanment of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of' 1978. 5 Prof. Oludarc Olajubu, personal communication. 6 This is a slang used to describe the wicked character Fadeyi, in Jimoh Aliu's popular film "Arelu" feature in 1987. 7 These interpretations were recorded from Radio ARIYA Kwara programme on Saturday , 22 October, 1988 and Saturday, 29 October, 1998, These interpretive possibilities exclude the nonsensical and funny interpretations some people gave. Barber, C.L. The Story of Language 5th Edition, Pan Books, London and Sydney, 1975. Euba, Akin. Dundun Music of the Yoruba Unpublished Ph.D Thesis, Legon, 1974. Finnegan, Ruth. Oral Literature In Africa, O.U.R N robi, 1970. Nketia, J.H. "The Role of Drummers in Akari Social Africa Vol. 1, No. 1, 1954. 8 Calling names is one of the most common forms of drum expression. Ogunsina, Bisi "A Study of Yoruba Political Songs 1955-1983" Paper presented at 1984/1985 Faculty Seminars Series, University of Ilorin, 11th June, 1985, 9 Dr. Tunde Ajiboye, personal communication. References Ajayi, Hade 'The Yoruba Drum Poetry: Ayanyemi Akokowagbowonle as a Case Siudy" Forthcoming in the LASU Book on AwUirtteS and Utilitarianism in Languages and Literature called by Dr. A.E. Eruvbetine. Olaniyan, O. The Composition and Techniques of Dundun Sekere Music of South Western Nigeria. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis Belfont, 1984. Olateju, Adesola "Surrogate Language; A form of Non, verbal Communicative Systems iimong die Yoruba paper presented al LASU Conference of Language Linguistics and Literatures, August 29 — September 1, 1988 Olatunji, O.O. Adebayo Taleti: A Study of his poems, 1954—1964 __"The Role of Yoruba Talking Drum in Social Mobilisation". ForLhcoming in Research in Yoruba Languages and Literature No. 3. ___"The Training of Yoruba Talking Drummers (1987- 88) ALORE: The Ilorin Journal of Humanities Vols. 3 &4 36 ‘BADE AJAYI Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation Heinemann, Ibadan, 1982 (a). 4. Milee redio ni’lorin A nfaani pupo lo wa Nilee redio ni’lorin ___ Ewi Adebayo Faleti Apa Kiini Heinemann Educational Books Ltd., Ibadan, 1982 (b). 5. Aye lohunbo je ku Omojola, O. Kiribofo Music In Oyo Town. Unpublished M.A. Thesis. 6. Ayanyemi omo Kikelomo Wiseman, Gordon and Larry Barker. Speech- Interpersonal Communication, Chandler Publishing Company, U.S.A. 1967. 7. Omola’ngidi Eni to bimo ti ko gbon, Omola’ngidi. APPENDIX A Test Interpretation of Drum Languages Conducted on 18/2/89 Tcsroh'rn'tcrprwfalion uf Drum Liinguagu Conducted on Words b&'itcn on the drum (Inlcndcd meaning). 9. Olorun Oba ni mo gbojule Olorun Oba ni mo feyin ti 8. Fadeyi oloro, afi suke suke 10. Beware le ku o ku, Beware le ku o ku Emi o le komi eeyan Ki n ko’mi eran Beware le ku o ku 1. E wenu imado, e wenu isin 2. Ade wale 3. Moji 12 .Sagari wole ekeji Awa o se ti baba mo.. 37 Yoruba Drum Language: A Problem of Interpretation 30 ‘BADE AJAYI