Exploring the long term effects of 'Thatcherite' social and

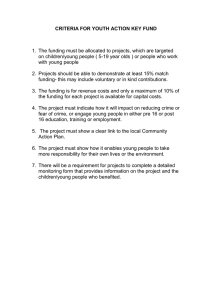

advertisement

Exploring the long term effects of 'Thatcherite' social and economic policies for crime Stephen Farrall (CCR, Sheffield Univ) Will Jennings (Politics, Soton Univ); and Emily Gray (CCR, Sheffield Univ). 29th April 2015; Southampton Univ. An Outline • Outlining our framework (and ‘dependent variable’) • How were crime rates related to Thatcherite social and economic policies? • What happened when crime rates rose? • Towards a conclusion … Our Approach: Drawing on Historical Institutionalism • Concerned with illuminating how institutions and institutional settings mediate the ways in which processes unfold over time. • Institutions do not simply ‘channel’ policies; they help to define policy concerns, create the ‘objects’ of policy and shape the nature of the interests in policies which actors may have. • Attempts to understand how political and policy processes and relationships play out over time coupled with an appreciation that prior events, procedures and processes will have consequences for subsequent events. What is HI? • Institutions are: “… the formal rules, compliance procedures, and standard operating practices that structure the relationship between individuals in various units of the policy and economy” (Hall, 1986: 19). • HI is concerned with illuminating how institutions and institutional settings mediate the ways in which processes unfold over time (Thelen and Steinmo, 1992: 2) • “… neither a particular theory nor a specific method. It is best understood as an approach to studying politics. This approach is distinguished from other social science approaches by its attention to real world empirical questions, its historical orientation and its attention to the ways in which institutions structure and shape political behaviour and outcomes.”. Steinmo, 2008. What is HI? • Institutionalists are interested in how institutions are constructed, maintained and adapted over time. • Institutions do not simply channel policies; they help to define policy concerns, create the objects of any policy and shape the nature of the interests in policies which actors may have. • Politics does not simply create policies; policies also create politics. HI is an attempt to develop understanding of how political and policy processes and relationships play out over time coupled with an appreciation that prior events, procedures and processes will have consequences for subsequent events. What are the main concepts within HI? • Path Dependencies: what happened at an earlier point will affect what can happen later. Reversal costs are high and institutional arrangements hard to completely ‘undo’. Policy concerns and interests become constructed within parameters. • Positive feedback loops: once a set of institutions is in place, actors, organisations and other institutions adapt their activities in ways which reflect and reinforce the path. • Timings and event sequences: both the timing and ordering of events can shape outcomes. • The speed of causal processes and outcomes: there are both fastand slow-moving causal processes and outcomes (cumulative, threshold and chain causal processes). Last two radically alter the time-frames of our explanations. What are the main concepts within HI? • Critical junctures: those rare and relatively short-lived periods when institutional arrangements are placed on a particular path. During these periods actors may be able to produce significant change. • Punctuated equilibrium: long-run stability in policymaking is subject to occasional seismic shifts when existing institutions and issue definitions break down and pressure for change accumulates to the point where is cannot be ignored. … and what are the problems with it? • ideas also matter too (not just institutions), so does HI underplay the importance of actors, perhaps?: • too much focus on reproduction of institutions? (similar to critiques of theories of structuration); • focus on political elites (little about the populous); • important to remember that not all institutions will be changed, adapted or maintained and that the speeds of change may be variable too. Figure 1: Property Crime Per Capita (Home Office Recorded Statistics and BCS) In which ways might this be a legacy of ‘Thatcherite’ policies? • Economic change • Changes in the housing market • Changes in social security provision • Changes in education policies (esp. after 1988) Economic Changes • During the 1970s there was a move away from the commitment to Keynesian policies and full employment. • Dramatic economic restructuring overseen by Thatcher governments. • Consequently, levels of unemployment rose through the 1980s (see Fig 2). Figure 2: Unemployment Rate (%), 1970-2006 Economic Changes This in turn led to increases in levels of inequality (Figure 3), augmented by changes in taxation policies which favoured the better off. Figure 3: Income Inequality (Gini coefficient), 1970-2006 The Economy and Crime in Post-War Britain • Using time series analyses for 1961-2006 Jennings et al (2012) find statistically significant relationships for: 1: the unemployment rate on the rate of property crime (consistent with other studies), 2: we also find that the crime-economy link strengthened during this period. 3: (economic inequality just outside bounds of significance). Housing Policy • 1980 Housing Act (+ others): created RTB – saw a huge rise in owner-occupation. • Created residualisation of council housing; transient/marginalised residents with low levels of employment (Murie, 1997). • Contributed to increases in inequality (Ginsberg, 1989) and concentration of crime (paper available on request). Social Security • 1980-1985: Some tinkering with the DHSS. • 1986 Social Security Act based on Fowler Review. • Following this payments reduced for many individual benefits claimants (whilst total spend increased due to unemployment). Social Security • Evidence to suggest that reductions in government expenditure are associated with rises in crime during the 1980s (Reilly and Witt, 1992). • Jennings et al (2012) suggest that increases in welfare spending is associated with declines in the property crime rate. Education • Changes in education policies encouraged schools to exclude children in order to improve place in league tables. • Exclusions rose during the 1990s, reaching a peak of 12,668 in 1996-97. Education • Dumped on the streets this fuelled ASB (Home Office RDS Occ. Paper No. 71). • The BCS 1992-2006 shows sudden jump of people reporting “teens hanging around” to be a problem from an average of 8% before 2001 to 30% after 2002. • School exclusions helped to create Labour’s discourse of ASB and need for C&DA 1998. British Crime Survey ASB items Anti-Social Behaviour (Common Problems) 4 Mean 3.5 3 2.5 2 1983 1988 1993 Noisy Neighbours Rubbish Abandoned Cars 1998 Year Vandals Drunks 2003 2008 2013 Teens Hanging Around Race Attack What happened to crime (etc)? • Rise in crime (Fig 5). This was generally rising before 1979, but the rate of increase picked up after early 1980s and again in early 1990s. • Fear of crime rises (tracks crime rates, Fig 6). • People want to see an increase in spending on the police/prisons (with decrease of spending on social security, Fig 7). Figure 5: Property Crime Per Capita (Home Office Recorded Statistics and BCS) Figure 6: Percentage worried about crime (BCS 1982-2005) Fig 7: Priorities for extra spending (social security vs. police) BSAS 1983-2009 Using these ideas in our research: Criminal Justice Acts 1982-1998 Charting Changes in State-led Punitiveness (1982-1998) Signifiers of Punitiveness Acts (by year of enactment) 82 Decreases in punitiveness Limits to the use of imprisonment 84 85 86 Increased rights for suspects Limits to police powers Increases in punitiveness Increased post-prison release/community controls Increases in police powers/resources Right to silence questioned or amended 93 94 96 97 Mandatory sentences (or similar provisions) Changes to the burden of proof ‘Failure to respond’ used in sentencing Increases in actual levels of imprisonment Increases in youth imprisonment Changes to case disclosure Limits to the use of bail Limits to the decision-making of parole boards Automatic life sentences Blurring of civil and criminal law 98 Increases in sentence lengths/imprisonment Unduly lenient sentences can be appealed 91 Diverting cases away from Crown Courts Decreases in actual levels of imprisonment 88 Temporality of Thatcherite Policy Spillover Developments post-1993: • Howard (Home Sec 1993-97) talks tough on crime. • Prison population rises immediately (Newburn 2007). • Rise in average sentences: Riddell 1989:170; Newburn 2007:442-4. • Trend continued, appears due to tough sentences and stricter enforcement. MoJ 2009: 2-3 cites mandatory minimum sentences (aimed at burglars and drug traffickers) as a cause. • Prison population grew by 2.5% p.a. from 1945 to 1995, but by 3.8% p.a. 1995-2009 (MoJ, 2009: 4). Making Sense of this Prison Popn 1970-2013 1970 1980 1990 year 2000 2010 Average Prison Popn (Key years): 1970: 39028 1979: 42220 1993: 44552 1994: 48621 2013: 84249 Labour Party’s Response • Move to the political right. • ‘Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. • Focus on ‘young offenders’ (Sch Exclusions related to?). • Did not oppose Crime (Sentences) Act 1997 despite it being quite draconian (‘3 strikes’, minimum mandatory sentences). Labour In Government Needed to do something about crime because … a) it actually was a problem (peak was in 1994) but still a source of public concern b) they needed to be seen to be doing something to avoid being accused of having ‘gone soft on crime again’. What have Govts done? • They devote more time to crime in it’s expressed policy agenda (Fig 9). • Little sustained interest in crime until 60s (2%). • After 1979 GE rises to 8%. • Big jump again in 1996 (15%). • Thereafter runs at or near to 20%. Figure 9: Proportion of attention to law and crime in Queen’s Speech (from policyagendas.org) What have Govts done? • Farrall and Jennings report statistically significant relationships for: 1: national crime rate on Govt attention on crime in Queen’s Speeches, and, 2: effects of public opinion on Govt. attention on crime in Queen’s Speeches. • So the Govt responds to crime rates and expressions of public concern about crime. Towards a Conclusion • Thatcherism was a mix of both neo-liberal and neo-conservative instincts. • Changes which were driven by neo-liberal instincts (housing, employment, social security and education) led to rises in crime. • Rises in crime ‘provoked’ a neo-conservative set of responses to crime (‘tougher’ prison sentences). This, and the improving economy, brought crime down. Towards a Conclusion • Thatcher’s legacy for crime and the criminal justice system has been the following: 1. Crime rise in 1980s-1990s. 2. New ‘consensus’ on responses to crime. 3. CJS now geared up for high volume crime (but crime rates falling). • Causes of crime therefore extremely complex and intertwined with other social policy arena. Figure 10: A model of Neo-Lib and Neo-Con policies and crime? Outline of current work ESRC grant : • Analyses of BCS, BSAS, GHS, BES + national level data. Data sets to be made available autumn 2015. • Training workshop (Manchester 20th May 2015) FULL • 40min documentary film made (Doc Fest 2015?) • http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/law/research/projects/crimetrajectories • Email newsletter (s.farrall@sheffield.ac.uk) • Twittering: @Thatcher_legacy Further Info/Readings Farrall, S. and Hay, C. (2010) Not So Tough on Crime? Why Weren’t the Thatcher Governments More Radical In Reforming the Criminal Justice System? British Journal of Criminology, 50(3):550-69. Farrall, S. and Jennings, W. (2012) Policy Feedback and the Criminal Justice Agenda: an analysis of the economy, crime rates, politics and public opinion in post-war Britain, Contemporary British History, 26(4):467-488. Farrall, S. and Jennings, W. (2014) Thatcherism and Crime: The Beast that Never Roared?, in Farrall S., and Hay, C. Thatcher’s Legacy: Exploring and Theorising the Long-term Consequencies of Thatcherite Social and Economic Policies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 207-233. Farrall, S. and Hay, C. (2014) Locating ‘Thatcherism’ In The ‘Here and Now’, in Farrall S., and Hay, C. Thatcher’s Legacy: Exploring and Theorising the Long-term Consequencies of Thatcherite Social and Economic Policies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 315-339. Farrall, S., Gray, E., Jennings, W. Hay, C. (2014) Using Ideas Derived from Historical Institutionalism to Illuminate the Long-term Impacts on Crime of ‘Thatcherite’ Social and Economic Policies: A Working Paper. Hay, C. and Farrall, S. (2014) Interrogating and Conceptualising the Legacy of Thatcherism, in Farrall S., and Hay, C. Thatcher’s Legacy: Exploring and Theorising the Long-term Consequencies of Thatcherite Social and Economic Policies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 3-30. Hay, C. and Farrall, S. (2011) Establishing the ontological status of Thatcherism by gauging its ‘periodisability’: towards a ‘cascade theory’ of public policy radicalism, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 13(4): 439-58. Jennings, W., Farrall, S. and Bevan, S. (2012) The Economy, Crime and Time: an analysis of recorded property crime in England & Wales 1961-2006, International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 40(3):192210.