Chapter 1 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

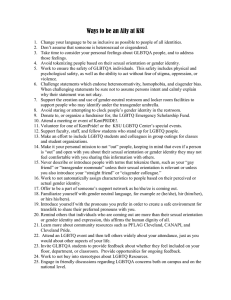

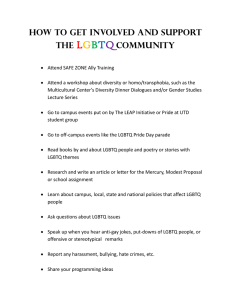

advertisement