August 14, 2002 Dear Sir:

advertisement

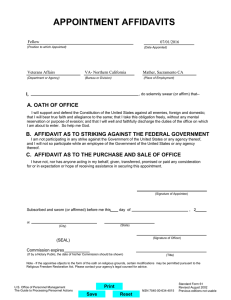

August 14, 2002 Dear Sir: You have the following question: What is the effect of the votes on the part of two new members of the city’s board of commissioners in a meeting of that board, where the two commissioners had taken the oath of office, but where the oath was administered by a person who did not have the authority to issue oaths for that purpose? Under the facts you related to me, the new members of the board of commissioners were de facto officers, and the votes they cast (and other acts they may have performed) during the period between which they were administered the oath of office by a person who was not authorized to administer oaths and at least the point at which that problem was brought to their attention, were legal. The facts are that: Two new members of the board were elected in the recent city election; at a meeting of the board following their election, they were administered the oath of office by the assistant city recorder, a city official who does not have the authority to issue oaths; following the seating of the two new members at issue, the board appointed a mayor, and voted on several other matters; the two commissioners at issue voted in the appointment of the mayor and in those other matters. There is no question but that the board had the authority to vote on the appointment of a mayor. The authority for that vote on the appointment derives from ' 3 of the City Charter. Presumably, there is no issue over the authority of the board to vote on the other matters. Section 3 of the Municipal Charter, provides that, “Before entering upon the duties of their offices, the commissioners shall take and subscribe an oath to faithfully perform their duties.” In Tennessee, numerous persons are authorized to issue oaths in specific cases. However, the general power to issue oaths is held by state judges (including some city recorders), city judges, state court clerks, county clerks, and notaries public. [Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 16-1-102, 16-18-301, 18-1-108, 8-16-302] It is said in Heard v. Elliot, 116 Tenn. 150 (1905), that: An officer de facto is one whose acts, though not those of a lawful officer, the law, upon principles of policy and justice, will hold valid, so far as they involve the interests of the public and third persons, where the duties of the office were exercised, first, without a known appointment or election, but under such August 14, 2002 Page 2 circumstances of reputation or acquiescence as was calculated to induce people, without injury, to submit to or involve his action, supposing him to be the officer he assumed to be; second, under color of a known and valid appointment or election, but where the officer had failed to perform some precedent requirement or condition, as to take an oath, give a bond, or the like; third, under color of a known election or appointment, void because the officer was not eligible, or because there was a want of power in the electing or appointing body, or by reason of some defect or irregularity in its exercise; such ineligibility, want of power, or defect being unknown to the public; forth, under color of an election or appointment by or pursuant to a public unconstitutional law before the same is adjudged to be such. [At 156] [Emphasis is mine.] The significance of being an officer de facto, is that the acts of officers de factor are generally valid. [See County Clubs, Inc. v. City of Knoxville, 395 S.W.2d 789 (1965); Butler v. Cocke County, 671 S.W 847 (Tenn. Ct. App. 1984); Smith v. Landsden, 370 S.W.2d 557 (1963); Inman v. Brock, 622 S.W.2d 36 (Tenn. 1981); Waters v. State ex rel Schmutzer, 583 S.W.2d 756 (Tenn. 1979); Weakley County Municipal Electrical System v. Vick, 309 S.W.2d 792 (1957).] The two commissioners clearly held office “under color of a known and valid appointment or election.” Their taking of seats before being administered an oath by a person qualified to administer oaths created de facto officers of the second kind. The specific question of whether a person who had not taken an oath prescribed by law was a de facto officer has been an issue at least twice in Tennessee. In Kelley v. James Story, 53 Tenn. 202 (1871), a deputy court clerk performed some duties without having taken the prescribed oath of office. Holding that the deputy court clerk was a de facto officer, the Court pointed to Farmer & Merchant’s Bank v. Chester, 25 Tenn. 458 (1848), and being “conclusive.” In that case, deputy court clerks were authorized to take deed for probate. Rose, took a deed for probate, but he had not take the oath of office for deputy court clerk. It was held that Rose was a clerk de facto. Pointing to yet another case, the Court said: Judge Wright says in the case of Venable v. Curd, 2 Head, 586, says: “No principle is better settled that the acts of an officer de facto are valid when they concern the public or the right of third persons who have an interest in the act done, and the rule has been adopted to prevent a failure of justice.” The rule is different when he acts for his own benefit, but when strangers or the public are concerned, who are presumed to be ignorant of the defect of title in the supposed officer, his act is always held good. August 14, 2002 Page 3 Here the party was publically acting as clerk in the office, the public had no notice of the failure to take the oath of office, and every reason applies to favor the validity of the act, to be found in any case in which the rule has been recognized. [At 206] [Emphasis is mine.] Country Clubs, Inc. v. City of Knoxville, 395 S.W.2d 789 (1965), although it does not deal with the failure of a public officer to take an oath prescribed by law, is also instructive on the law of de facto offices where the officer at issue has been validly elected. There the plaintiff sought to have the office of Mayor of the City of Knoxville declared vacant because Mayor Rogers had failed to file a record of his campaign expenses as required by the city’s charter. The city’s charter provided that “...any elective officer, failing to comply within the requirements of this act shall be disqualified from holding the office he seeks, or to which he has been elected.” [At 790] One of the issues in that case was whether a city employee fired by Rogers had standing to bring the suit as a taxpayer. Holding that the answer was no, the Court reasoned that the fired city employee had suffered no special injury because all of Roger’s acts were “at least the acts of a de factor Mayor....” [At 793] Said the Court on that point: It is enough to say that when a person is occupying a public office and performs the duties of this office he is a “de facto officer,” even though he may not have legally been appointed or elected to the office where he holds apparent right under color of title. The bill here shows that Rogers did receive the majority of votes and was then sworn in as Mayor, but the basis of attacking him as a usurper in this office is that he failed to comply with Section 92 of the Charter.... The law validates the acts of “de facto” officers as to the public and third persons on the ground, though not officers de jure, they are in fact offices whose acts, public policy requires, should be considered valid....[At 793] [Emphasis is mine.] The two commissioners at issue in the City were validly elected; for that reason they held their offices “by apparent right under color of title.” They had even took the oath of office as required by ' 3 of the Municipal Charter. The only defect in the title to their offices is that they took the oath from a person who was not qualified to issue oaths. Based on the above cases, it is almost impossible to believe that they were not at least de facto officers with respect to the votes they cast as a part of the majority of the board voting for the appointment of the mayor, and with August 14, 2002 Page 4 respect to other votes they cast as members of the board. Sincerely, Sidney D. Hemsley Senior Law Consultant SDH/