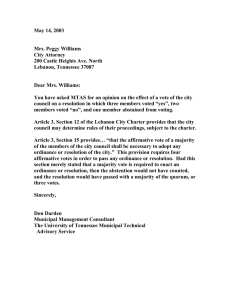

November 12, 2001 Dear Sir:

advertisement

November 12, 2001 Dear Sir: You have the following question: Can an ordinance providing for the expiration of [apparently residential] building permits after 18 months, and for two 90 day extensions for cause, be made to apply to existing building permits? In my opinion, the answer is yes. Under the facts you related, a residential building permit was issued four years ago, and the home for which it was issued is still not complete. Work is periodically done on the building, but the work quits. There is no indication of when, if ever, the construction on the building will be complete. Under what I assume is proposed Ordinance No. 001-00-00, building permits expire after 18 months from original date of issue. Two 90 day extensions for cause are allowed. [4-106] Any structure that is not completed prior to the expiration of the building permit, or any extensions, is to be demolished, and the site returned to its natural state within 90 days of the expiration of the permit or any extensions. [4-107] Article I, Section 20, of the Tennessee Constitution, provides, “That no retrospective law, or laws impairing the obligations of contracts, shall be made.” However, a long line of cases holds that Article I, Section 20, does not apply to the exercise of the police power of the state, including the police power of the state delegated to municipalities, and that all contract rights are subject to both the retrospective and prospective exercise of the police power. [Marr v. Bank of Tennessee, 72 Tenn. 578 (1880); Shields v. Clifton Hill Land Co., 28 S.W. 668 (1894); Draper v. Haynes, 567 S.W.2d 462 (Tenn. 1978). Also see Paris v. Paris-Henry County Public Utility District, 240 S.W.2d 885 (1960), and many other cases.] There is no question but that the adoption of building codes and regulations, including reasonable deadline dates for completion, are within the delegated police power of municipalities. [See especially Thomas v. Chamberlain, 143 F. Supp. 671 (E.D. Tenn. 1955), aff’d 236 F.2d 417 (6th Cir. 1956), and Winters v. Sawyer, 463 S.W.2d 705 (1971)] Such completion dates promote the health, safety and welfare of the citizens of the city, which is the essence of the police power. [Penn-Dixie Cement Corporation v. Kingsport, 225 S.W.2d 270 (1949); Spoone v. Morristown, 206 S.W.2d 442 (1947); Consumers Gasoline Stations v. Pulaski, 292 S.W.2d 735 (1956); Corporation of Knoxville v. Bird, 80 Tenn. 1212 (1883); Garrell v. Newport, 1 Tenn. Ch. App. 120 (1901)]. Generally, under the rules of statutory construction (which also apply to ordinances), a statute operates only prospectively, unless a clear, unequivocal intent otherwise is evidenced in its provisions, and when a statute is capable of being read to apply retrospectively or prospectively, it will be read to apply only prospectively. [Hannum v. Bank of Tennessee, 41 Tenn. 398 (1860); Woods v. TRW, Inc., 557 S.W.2d 274 (Tenn. 1977); Kee v. Shelter Ins., 852 S.W.2d 398 (Tenn. 1993); James Cable Partners v. City of Jamestown, 43 F.3d 277 (6th Cir. November 12, 2001 Page 2 1995); Westland Drive Service Co. v. Citizens & S. Realty Investors, 558 S.W.2d 439 (Tenn. Ct. App. 1977); Menefee Crushed Stone Co. v. Taylor, 760 S.W.2d 223 (Tenn. Ct. App. 1988).] For that reason, the proposed ordinance must unequivocally provide that it applies to structures for which a building permit has already been issued. The ordinance provides that if a building is not completed by the deadline, including any extensions, it is to be demolished, and the property returned to its natural site within 90 days. I doubt that remedy would be reasonable in many cases. I suspect even where the deadline and any extensions, have passed, the courts would have a tough time upholding the demolition of a building that is substantially complete, or that is not complete for reasons beyond the control of the owners or builders, but that otherwise does not constitute an immediate threat to the safety of the citizens of the city. The city has adopted the Unsafe Building Abatement Code, 1985 Edition. Under Section 303 of that code, a building that is unsafe as defined by Section 202 of that code, “...shall be ordered repaired in accordance with the Standard Building Code or demolished at the option of the owner.” Chapter 3 of that code outlines the procedure for the demolition of the building if it is not repaired within the time prescribed by that chapter. There is also available for adoption by the city a “Slum Clearance Ordinance” under Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 13-21-101 et seq. That ordinance provides for the demolition of certain structures that for the reasons contained in the ordinance are not amenable to repair, and is the ordinance upheld by the Tennessee Supreme Court in Winters v. Sawyer, 463 S.W.2d 705 (1971). The city has not adopted that ordinance; I have enclosed a sample copy for your consideration. The demolition of structures on the part of a city is a legally hazardous enterprise, and should be done only when there are compelling reasons for it. The Tennessee Supreme Court in Winters v. Sawyer, above, observed that an ordinance “...after notice and a hearing, all subject to judicial review, requires the repair or removal of dwellings found hazardous to the health, safety or morals of the community.” While the Court upheld the validity of the ordinance, it also declared that it “will again reiterate the statement of Mr. Justice Green in Jackson v. Bell, supra, that such statute or ordinance should be administered with caution.” [At 706] The Court went on to note that the order of removal applied five buildings, “four of which, among other things, are shown to be fire hazards due to inadequate electrical wiring. The fifth dwelling is shown to be in very dilapidated condition.” [At 706] Caution on the part of the in demolishing buildings is well-advised. It has been pointed out that one of the greatest potential liabilities for municipalities in the code enforcement area is the demolition of dangerous structures, and that many lawsuits arise in this area. [Banks, Marianne Landers, City Attorney, Georgetown, Texas, Practical Tips for Limiting Liability for Municipal Code Enforcement, Banks, Paper, IMLA Conference, October 8, 1996.] Section VI of that paper has an excellent list of things a city needs to consider before it decides to demolish a building. November 12, 2001 Page 3 Sincerely, Sidney D. Hemsley Senior Law Consultant SDH/