THE RELATIVE IMPACT OF ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL FACTORS IN U.S.

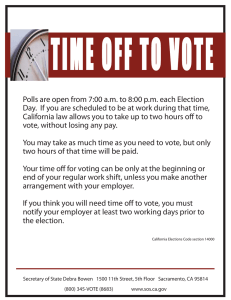

advertisement