PRESENTING DIFFICULT NEWS TO PARENTS AND THE IEP TEAM: A

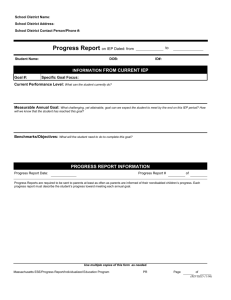

advertisement