THE EFFECTS OF MANIPULATING MOTIVATING OPERATIONS ON THE

OUTCOME OF EXTINCTION

A Thesis

Presented of the faculty of the Department of Psychology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Psychology

by

Lindsey Kathryn Dukes

SUMMER

2012

THE EFFECTS OF MANIPULATING MOTIVATING OPERATIONS ON THE

OUTCOME OF EXTINCTION

A Thesis

by

Lindsey Kathryn Dukes

Approved by:

____________________________, Committee Chair

Becky Penrod, Ph.D.

____________________________, Second Reader

Caio Miguel, Ph.D.

____________________________, Third Reader

Jill Young, Ph.D.

Date: ___________________________

ii

Student: Lindsey Kathryn Dukes

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

_______________________, Graduate Coordinator

Jianjian Qin, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

iii

_______________

Date

Abstract

of

THE EFFECTS OF MANIPULATING MOTIVATING OPERATIONS ON THE

OUTCOME OF EXTINCTION

by

Lindsey Kathryn Dukes

This study examined the effect of manipulation of motivating operations prior to

intervention on the outcome of the extinction procedure for two children with

developmental disabilities who displayed problem behavior maintained by access to

attention. Following replication of previous studies which showed that problem behavior

occurred at a lower rate during extinction sessions following pre-session non-contingent

access to attention, participants were repeatedly exposed to pre-session non-contingent

attention followed by extinction over many sessions. Results showed that responding for

both participants remained below baseline levels when pre-session attention was no

longer provided. This suggests that the extinction procedure remained effective when

combined with pre-session exposure to the maintaining reinforcer. Implications for

addressing potentially injurious or severe problem behaviors are discussed.

___________________________, Committee Chair

Becky Penrod, Ph.D.

___________________________

Date

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to extend my thanks to my thesis advisor Becky Penrod, Ph.D., for all of her

support through the process of completing this thesis. Thanks are also due to my thesis

committee, Caio Miguel, Ph.D., and Jill Young, Ph.D., who have provided me with

valuable feedback and insight regarding my research. I would also like to thank my

family for their support and assistance in helping me reach this point. Finally and most

importantly, I need to thank my wonderful husband, Donny Dukes, without whose

continuous support, help, and encouragement I would not have been able to complete this

process. I love you, pie!

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………v

List of Figures………………………………………………………..…………….……vii

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………..………………….…1

Review of Research……………………………………..…………………….….1

Purpose………………………………………………….………………….……15

2. METHOD………………………………………………….……...………………...16

Participants and Setting…………………………………….….………………..16

Response Measurement…………………………………….………….………...16

Preference Assessments……………………………………………….………...18

Functional Analysis…………………………………………….…..…...……….19

Experimental Design…………………………………………….……….……...20

3. RESULTS………………………………………………………..…..….………..….22

Preference Assessments...………………………………………………….….…22

Functional Analysis…………………………………………………….…….….24

Experimental Conditions………………………………………………..….……26

4. DISCUSSION……………………………………………………….……….….…..29

References…………………………………………………………..…………….……...36

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1. Preference assessment results for Helen...……….…………………………………22

2. Preference assessment results for Vincent…………………………………………24

3. Functional analysis results for both participants..………….………………………25

4. Intervention results for both participants..…….……………………………………27

vii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Many topographies of problem behavior have been found to be maintained by

social positive reinforcement in the form of attention, including aggression (Thompson,

Fisher, Piazza, & Kuhn, 1998), self-injurious behavior (O’Reilly, Lancioni, King, Lally,

& Dhomhnaill, 2000), and even bizarre vocalizations in patients with schizophrenia

(Wilder, Masuda, O’Conner, & Baham, 2001). Common treatments used to eliminate

behaviors maintained by social positive reinforcement include consequence

manipulations, such as differential reinforcement (e.g., Kahng, Hendrickson, & Vu, 2000;

Repp & Deitz, 1974) and extinction (e.g., France & Hudson, 1990); these interventions

may also be applied in combination (e.g., Shukla & Albin, 1996). Other common

treatments include antecedent manipulations, such as noncontingent reinforcement (e.g.,

Van Camp, Lerman, Kelley, Contrucci, & Vorndran, 2000) and satiation (e.g., O’Reilly,

Edrisinha, Sigafoos, Lancioni, & Andrews, 2006).

Review of Research

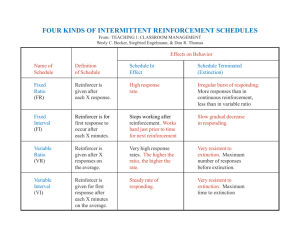

Consequence manipulations such as extinction (EXT), the withholding of a

stimulus that previously reinforced a behavior, are popular interventions typically used to

eliminate problem behaviors. The EXT procedure may be used independently (e.g.,

France & Hudson, 1990) or in combination with a variety of other procedures, including

differential reinforcement (e.g., Shukla & Albin, 1996). Differential reinforcement of

other behavior (DRO) and differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA)

2

involve presenting a reinforcer periodically in the absence of a target behavior, or upon

the occurrence of some alternative behavior, and are among the most widely used

procedures for decreasing problem behavior (Volmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, &

Mazaleski, 1993). Several studies have demonstrated that withholding the reinforcer that

previously followed the occurrence of the target behavior as well as presenting a stimulus

contingent upon some behavior other than the target behavior not only decreases the

frequency of the target behavior but also teaches the individual an alternative, more

appropriate means of obtaining reinforcers (France & Hudson; Kahng et al., 2000; Repp,

& Deitz, 1974). Although there is an abundance of research that supports the use of

consequence-based interventions such as EXT, there are several undesirable side effects

associated with such procedures.

Lerman, Iwata, and Wallace (1999) examined 41 studies in which an EXT

procedure was used, and found that in 41% of the studies there was an increase in the

frequency and intensity of the target behavior, an increase in emotional or aggressive

behavior, or an increase in both the target behavior and emotional or aggressive behavior

within the first three sessions of the EXT procedure. They further found that when the

EXT procedure was implemented as the sole behavior change procedure, an extinction

burst was observed in 62% of studies, and extinction-induced aggression was observed in

29% of studies. When the EXT procedure was implemented in combination with other

procedures, such as differential reinforcement, undesirable side effects were less

common, but extinction bursts and extinction-induced aggression were still observed to

occur in 15% of the studies evaluated. The prevalence of these side effects may make

3

such a procedure undesirable when addressing potentially dangerous behaviors such as

self-injurious behavior and aggression.

DRA includes an EXT component, in that reinforcement is withheld following

occurrences of the problem behavior and provided contingent upon the occurrence of

some alternative behavior. While not as common, DRA procedures can sometimes result

in negative side effects characteristic of EXT procedures, such as extinction bursts. For

example, Piazza, Moes, and Fisher (1996) observed significant increases in aggression

over the observed baseline rate when initially implementing DRA with extinction to

eliminate escape-maintained aggression in an 11-year-old boy with autism. Another

challenge associated with DRA procedures is finding an alternative response that is less

effortful than the previously reinforced problem behavior. Also, when first implemented,

DRA procedures may require frequent or continuous observation of the individual in

order to ensure that each instance of the alternative behavior contacts reinforcement.

An exception is when the alternative response is a communication response, in

which the individual is able to recruit reinforcers (e.g., attention, access to tangible items)

from others in their environment; however, finding an alternative communication

response that is less effortful than the previously reinforced problem behavior can

represent a significant challenge. Also, providing reinforcement for each alternative

response may be too cumbersome for caregivers (Roane, Fisher, Sgro, Falcomata, &

Pabico, 2004). In addition, some individuals may have an extremely limited repertoire of

potential communication skills, which limits the utility of the DRA procedure.

4

DRO, a consequence manipulation frequently used to address potentially

dangerous behaviors, involves EXT, in that reinforcers for the target behavior are

withheld, and instead, are delivered contingent on any behavior other than the target

behavior (Miltenberger, 2011). In other words, reinforcers are delivered contingent on the

absence of the problem behavior. Although EXT is an inherent component of DRO, DRO

may not occasion bursts of inappropriate behavior given that reinforcers are still being

delivered; however, this procedure does have other drawbacks. In order to determine the

initial time interval for providing reinforcement contingent on the absence of the problem

behavior, interresponse time (i.e., the time that elapses between each occurrence of the

problem behavior) must be measured. It is recommended that the initial interval be set

slightly below the average interresponse time. Also, when first implementing an interval

DRO procedure, the entire interval must be free of problem behavior in order for the

individual to gain access to reinforcement (Milternberger, 2011). As a result, this

procedure requires constant or near constant observation of the individual during the

initial stages, which may compromise the integrity of such treatments in the natural

environment.

There have also been a number of studies that have evaluated the effects of

reinforcing an alternative behavior while continuing to provide reinforcement for the

problem behavior. Because the problem behavior continues to be reinforced, an EXT

burst is seldom observed, but this procedure can have other drawbacks. Typically when

using this DRA procedure, each instance of the alternative behavior must be followed by

the reinforcer in order for responding to continue to be allocated to the alternative

5

behavior rather than the inappropriate behavior. For example, Worsdell, Iwata, Hanley,

Thompson, and Kahng (2000) demonstrated that several participants were able to acquire

and use functional communication skills taught using a DRA procedure even when

problem behavior continued to result in intermittent reinforcement, but also found that

even small errors in the delivery of the reinforcer compromised treatment effects. More

specifically, participants only allocated responding to the appropriate functional

communication response, rather than the problem behavior, if reinforcement for the

appropriate behavior was provided on a continuous or fixed ratio (FR) 1 schedule, while

reinforcement for the problem behavior was provided on an intermittent schedule.

In an effort to address the limitations associated with consequence-based

interventions, research has also been conducted on antecedent manipulations that can be

used to decrease the occurrence of problem behavior. Antecedent manipulations used to

decrease problem behaviors maintained by positive reinforcement often involve altering

the motivating operation (MO) that affects the likelihood of the target behavior occurring.

An MO is defined by Michael (1982) as “any change in the environment which alters the

effectiveness of some object or event as reinforcement and simultaneously alters the

momentary frequency of the behavior that has been followed by that reinforcement” (p.

150). More specifically, MOs have two main effects: the value-altering effect, which

refers to the change in the effectiveness of a stimulus as a reinforcer and includes both

establishing (value-increasing) and abolishing (value-decreasing) functions, and the

behavior-altering effect, which refers to the momentary change in the frequency of

behavior that has previously resulted in that reinforcer, and includes both evocative

6

(behavior-increasing) and abative (behavior-decreasing) functions (Laraway, Snycerski,

Michael, & Poling, 2003). Two primary treatment techniques have been developed to

manipulate MOs for behavior maintained by positive reinforcement: noncontingent

reinforcement and satiation procedures.

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) is an antecedent intervention consisting of

the periodic presentation of a stimulus independent of the organism’s behavior. In applied

research, this consists of presentation of either the maintaining reinforcer for the target

behavior or an arbitrary but preferred stimulus. When the reinforcer presented is the same

as the stimulus maintaining the behavior, this manipulation is functionally similar to

extinction in that the contingency between the behavior and the reinforcer is disrupted;

moreover, the delivery of a functional reinforcer on a time-based schedule eliminates the

MO for the behavior (Kahng, Iwata, Thompson, & Hanley, 2000; Wilder & Carr, 1998).

When the noncontingent reinforcer presented is arbitrary but preferred, a stimulus for

which a competing MO is in effect has been introduced, which may result in a shift in

responding from the target behavior to another behavior (Lindberg, Iwata, Roscoe,

Worsdell, & Hanley, 2003).

NCR has been demonstrated to be an effective behavior reduction procedure for

problem behaviors maintained by positive reinforcement, and has further been shown to

address several of the limitations seen with consequence interventions. For example,

Vollmer et al. (1993) directly compared NCR and EXT procedures in the treatment of

self-injurious behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement, and found that

although both procedures were equally effective in decreasing the frequency of the target

7

behavior across sessions, fewer responses occurred per session during the NCR condition

for 2 of the 3 participants. Hence, NCR procedures may be preferred relative to EXT

when treating potentially dangerous behavior.

While NCR procedures require less time on the part of the individual

implementing the treatment and have been associated with fewer negative side effects

than many consequence interventions, these procedures are not without their own

limitations. For example, Lindberg et al. (2003) found that NCR was effective in

reducing problem behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement over a short period of

time (short session durations are typical in much of the research on NCR), but when NCR

was implemented over a longer period of time, the target behavior increased for several

participants. These results suggest that prolonged access to a single reinforcing stimulus

will not result in decreased responding for an extended period of time, even if a

significant decrease is initially observed; however, it should be noted that in this study no

attempt was made to match the function of the stimulus that was delivered to the function

of the target behavior. Therefore, the extent to which the noncontingent delivery of a

functionally matched stimulus would suppress responding over time is not known.

Additionally, because NCR has been demonstrated to work by decreasing or eliminating

the MO that evokes the target behavior (Kahng et al., 2000), treatment effects are not

likely to persist in the absence of continued presentation of noncontingent reinforcers. In

contrast, consequence interventions such as DRA and EXT may produce more lasting

changes in behavior due to allocation of responding away from behaviors that do not

produce reinforcement (problem behaviors) and toward behaviors that do produce

8

reinforcement (alternative behaviors). Also, interventions such as DRA increase the

individual’s control over the environment, as these interventions provide individuals with

a way to recruit their own reinforcers when a MO is in place, unlike NCR procedures in

which stimuli are provided noncontingently regardless of the actions of the individual.

The second type of MO manipulation used to address behavior maintained by

positive reinforcement is commonly referred to in the literature as satiation. This type of

intervention involves providing continuous access to the stimulus identified to maintain

the target behavior prior to the initiation of a treatment session (O’Reilly, Sigafoos, et al.,

2006). This differs from NCR in that reinforcement is not necessarily scheduled during

the treatment session itself, but unlimited access to the reinforcer is provided for some

period of time immediately prior to the initiation of the session in an effort to minimize

responding during treatment. Responding may be decreased due to the value-abolishing

and behavior-abative effects of unlimited access to the stimulus that functions as a

reinforcer for the problem behavior.

Rapp (2006) demonstrated the effectiveness of this procedure when compared to a

response-blocking procedure used to reduce the frequency of automatically reinforced

behavior in one participant. In this study, each session consisted of 15 minutes of

baseline, during which the experimenter did not interact with the participant, 15 minutes

of intervention, and 15 minutes of a post-intervention condition that was identical to

baseline. Intervention varied, and involved either a satiation procedure, during which the

participant was provided with unlimited access to several toys that produced the same

sensory consequences as the target behavior, or a response-blocking procedure, during

9

which all attempts to engage in the target behavior were physically blocked by the

experimenter. Results of this study showed that in the post-intervention conditions

following the satiation intervention, rates of responding were lower than those observed

in baseline sessions, while in the post-intervention conditions following the responseblocking sessions, rates of responding were higher than those observed during baseline

sessions. This finding demonstrates that noncontingent access to a matched stimulus may

result in decreased responding when noncontingent access is discontinued, which

suggests that noncontingent access to a matched stimulus has an abolishing effect on the

MO for the automatically reinforced behavior. In contrast, the response-blocking

procedure, in which the behavior was prevented from occurring for a period of time,

seemed to have an establishing effect on the MO for the automatically reinforced

behavior. If the response-blocking procedure is considered to be an opposing intervention

to the satiation procedure, this result is not unexpected.

O’Reilly and Sigafoos et al. (2006) used the satiation procedure to address selfinjurious behavior, aggression, and elopement which were determined by a functional

analysis to be maintained by positive reinforcement in the form of access to food for one

participant (Sam) and access to attention for the other participant (John). In this study, the

authors provided participants with ongoing noncontingent access to the maintaining

reinforcer for 10 min for Sam and 15 min for John prior to some treatment sessions

(called the pre-session access condition) and withheld the maintaining reinforcer for two

hours for Sam and 15 min for John prior to other treatment sessions (called the presession no access condition). Pre-session access and pre-session no access conditions

10

were evaluated using a multielement design. Treatment sessions during the first phase of

the study mimicked the attention condition of the functional analysis, in which attention

was provided contingent upon the occurrence of the problem behavior on a FR 1

schedule, and participants were otherwise ignored. In the second phase participants were

ignored regardless of behavior, following an EXT procedure. Results showed that rates of

problem behavior for both participants were higher in treatment sessions following the

pre-session no access condition, both when the problem behavior was resulting in

reinforcement and during the EXT phase. For one participant, overall rates of problem

behavior were markedly higher in treatment sessions following the pre-session no access

condition during the EXT phase, and even exceeded rates of problem behavior observed

during the functional analysis. The authors suggested that the satiation procedure is a

viable alternative to consequence manipulations such as EXT and DRO procedures.

O’Reilly and Edrisinha et al. (2006) conducted another study to investigate the

effects of continued access to reinforcement for problem behavior in treatment sessions

following presession access and pre-session no access conditions when compared to

EXT. The study was conducted in two phases; in the first phase, the maintaining

reinforcer was available during the treatment sessions, and in the second phase the EXT

procedure was implemented during the treatment sessions. In the first phase, during the

pre-session access condition, the participant was provided with access to the maintaining

reinforcer (attention) continuously for 15 min prior to the treatment session, while during

the pre-session no access condition, the participant was placed alone in a room for 15 min

prior to the treatment session. All treatment sessions were 5 min in duration, and during

11

sessions the participant sat in a room with the experimenter, with leisure items such as

pens and paper available. The experimenter provided the participant with a brief verbal

instruction contingent upon occurrences of the target behavior, but otherwise did not

interact with the participant. Results of this phase showed that even when the target

behavior continued to come into contact with the reinforcer, rates of the target behavior

were significantly lower in treatment sessions following the pre-session access condition

than in treatment sessions following the pre-session no access condition. In the second

phase of this study, the procedures were identical, with the exception that during sessions

all occurrences of the target behavior were ignored. Results of this phase showed that the

behavior occurred at a significantly lower rate in treatment sessions following the presession access condition than in treatment sessions following the pre-session no access

condition when EXT was implemented. As noted by the authors, this reduction suggests

that the satiation procedure is a desirable alternative to consequence-based interventions;

furthermore, such a procedure may be beneficial when implemented in conjunction with

EXT in that it may minimize the extinction burst and decrease rates of behavior more

rapidly.

In another study on satiation, O’Reilly et al. (2007) investigated the effects of the

satiation procedure on self-injury and aggression maintained by access to food. In this

study, pre-session access to the reinforcer involved unlimited access to preferred snacks

for 15 min immediately prior to an instructional session, and pre-session no access

involved withholding food for a minimum of 2 hours prior to the session. All

instructional sessions were 10 min in duration. Throughout all sessions the preferred food

12

was kept in a transparent container on a table out of the participant’s reach, and all

occurrences of the target behaviors were ignored, essentially duplicating an EXT

procedure. This intervention was implemented in a multielement design, and results

showed that inappropriate behaviors occurred at a significantly lower rate in treatment

sessions following the pre-session access condition (occurring at an average rate of 2

incidents per session) than in treatment sessions following the pre-session no access

condition (occurring at an average rate of 34.9 incidents per session), despite the

continued presence of the discriminative stimulus (SD) throughout the instructional

sessions in both conditions.

In a more recent study on the effects of pre-session access to reinforcement,

Rispoli et al. (2011) examined the effects of the satiation procedure on aggression and

inappropriate vocalizations maintained by access to tangible items. In this study, presession access to the reinforcer involved providing each participant with unlimited access

to desired tangible items until the participant rejected playing with the item(s) three times

within a session. Rejection was defined as transferring the preferred item to the nondominant hand while manipulating other items or dropping the item and failing to pick it

up within 3 s. As a result, the duration of the pre-session access condition was not fixed,

and averaged from 11 to 52 min across both participants. During the pre-session no

access condition, participants were provided with access to typical classroom materials,

but were not provided with access to desired tangible items for a minimum of 2 hours

prior to sessions. All instructional sessions were 20 min in duration. During instructional

sessions, desired items were visible to the participants, but placed out of their reach.

13

Participants were seated at a table with several other students and a teacher, and were

provided with classroom materials. The teacher modeled appropriate engagement with

the materials, but did not prompt the students to manipulate the materials. Target

behaviors were ignored. This intervention was implemented in a multielement design,

and results showed that inappropriate behaviors occurred at a significantly lower rate in

treatment sessions following the pre-session access condition (occurring at an average of

20% of session intervals) than in treatment sessions following the pre-session no access

condition (occurring at an average of 61% of session intervals), despite the continued

presence of the SD throughout the instructional sessions in both conditions. The authors

concluded that the differences in responding during treatment sessions following presession access versus pre-session no access conditions were due to the abolishing and

abative effects of unlimited access to desired items on the MO affecting the inappropriate

behavior that had previously resulted in access to those items. The authors noted that this

procedure might be useful when combined with the EXT procedure, as it may eliminate

or reduce such side effects as the extinction burst.

The significant reduction in occurrences of problem behavior observed in studies

using pre-session exposure to reinforcement has prompted several researchers to

recommend this procedure as a viable alternative to consequence-based manipulations

and NCR procedures for some challenging behaviors. This intervention may be preferred

when addressing behaviors that are potentially dangerous, and for which an extinction

burst may result in serious injury, and also when attempting to address challenging

behavior in an environment in which continuous observation of the individual is very

14

difficult to ensure, or in which frequent presentation of a stimulus or a variety of stimuli

throughout the day (as in the case of the NCR procedure) may be disruptive or otherwise

undesirable, such as in a typical classroom setting. However, there are limitations of

previous research on satiation interventions that must be addressed before such a

recommendation can be adopted.

One significant limitation inherent in the satiation intervention is that like the

NCR procedure it is an antecedent-based manipulation, and as a result will not have a

long-term effect on the rate of responding when the treatment is not in effect, unlike

consequence-based interventions which can result in long-term behavior change

(Chandler & Dahlquist, 2006). In response to this limitation, O’Reilly and Edrisinha et al.

(2006) suggested that the satiation procedure might have additional benefits when

combined with a consequence-based intervention such as EXT. When the satiation

procedure is combined with EXT, undesirable side effects associated with EXT can be

avoided and changes in behavior may be longer lasting. This recommendation to combine

antecedent-based and consequence-based interventions is not uncommon in applied

settings (see Chandler & Dahlquist), but is less common in peer-reviewed research,

which typically attempts to isolate the effects of a single intervention on behavior.

However, it is possible that combining satiation with EXT will not be an effective

treatment package. It is assumed in the definition of extinction that a relevant MO is in

effect when responding occurs (Michael, 1993/2003). Given that the value of the

reinforcer is temporarily abolished during the satiation procedure due to the MO

manipulation in the pre-session access conditions, little or no responding would be

15

observed, in which case extinction would not occur at all, and responding would still be

expected to occur when the MO is again in effect despite the use of the EXT intervention.

However, it should also be noted that in all research on the satiation intervention, the

target behavior did continue to occur, albeit at a very low rate, during the sessions

following pre-session access to the maintaining reinforcer. This suggests that pre-session

exposure diminishes but does not entirely eliminate the MO for the behavior. As a result,

it is possible that the EXT procedure could still be effective despite the decrease in the

rate of responding when the satiation procedure is used. If so, satiation may indeed be a

desirable addition to the EXT treatment, especially when addressing potentially

dangerous or highly injurious behaviors, due to the observed decrease in such undesirable

side effects such as extinction bursts.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to replicate and extend the study conducted by

O’Reilly and Sigafoos et al. (2006) by investigating the effects of pre-session exposure to

reinforcement on behavior undergoing EXT to determine whether combining pre-session

exposure with an EXT procedure would decrease the occurrence of undesirable side

effects commonly observed during EXT procedures. An additional purpose was to

determine whether the EXT procedure remains effective when applied in combination

with the pre-session exposure procedure, despite the abolishing effect of exposure to the

maintaining reinforcer on the MO for the problem behavior, by determining whether

decreased responding following pre-session exposure plus EXT is maintained when presession exposure is no longer in place and EXT is implemented in isolation.

16

Chapter 2

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Two children with developmental disabilities who engaged in problem behavior

(e.g., aggression, tantrums) maintained by social positive reinforcement participated.

Participants were recruited through direct contact with schools and in-home service

providers who serve children and young adults with developmental disabilities. Helen

was a 7-year-old girl with a primary diagnosis of Angelman syndrome who attended a

non-public school for children with disabilities and received 25 hours per month of inhome ABA services. Vincent was a 6-year-old boy diagnosed with Prader Willi

syndrome and ADHD. Vincent attended a special education full-day Kindergarten class

in a public elementary school, and was taking 5 mg of methylphenidate twice daily

throughout the duration of this study. Sessions were conducted in participants’ homes, in

their bedrooms, which were furnished with a bed, table, several chairs, shelves, and

leisure materials. Bedrooms ranged in size from approximately 12’ x 15’ to 15’ x 20’.

Sessions were 25 min in duration, including 15 min of pre-session exposure or no

exposure to reinforcement, followed by a 10-min treatment session. Two to three sessions

per week were conducted, participant schedules permitting.

Response Measurement

Data were collected using a frequency within interval procedure for Helen, and a

partial interval procedure for Vincent. The specific data collection procedure for each

17

participant was selected based on the types of problem behavior displayed. Helen’s target

problem behaviors included hitting, defined as bringing her hand into contact with any

part of another’s body hard enough to produce an audible sound; kicking, defined as

bringing her foot into contact with any part of another person’s body hard enough to

leave a lasting mark; pulling hair, defined as grasping another person’s hair in her hands

and pulling hard enough to move the person’s head; grabbing, defined as grasping items

that are in another person’s possession and pulling on them hard enough to move them;

and pressing her face into others, defined as pressing her face against any part of another

person’s torso or lap. The frequency of occurrence of the target behaviors was recorded

within 10-s intervals, to determine both the percentage of intervals during which the

target behavior occurred in each session, and any patterns of responding that occurred

within each session. Vincent’s target problem behaviors included yelling or screaming,

defined as emitting a sound loud enough to be heard clearly through the door and

maintaining the sound for at least 3 s; crying, defined as emitting high-pitched nonverbal

vocalizations for at least 3 s; and dropping to the ground, defined as falling to the ground

and remaining in a prone position for at least 5 s. The occurrence of the target behaviors

during any part of a 10-s interval was recorded, in order to determine the percentage of

session intervals during which problem behavior occurred.

A second observer independently collected data on each participant’s behavior

during approximately 36% of all sessions. Interobserver agreement was calculated for

frequency within interval data by calculating the number of intervals in which both

observers recorded the same number of target behaviors, and then dividing the number of

18

agreement intervals by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and dividing

by 100, in order to determine the percentage of agreement. Interobserver agreement was

calculated for partial interval data by calculating the number of occurrence and

nonoccurrence intervals in which both observers agreed, and then dividing the number of

agreements by the total number of agreements plus disagreements and dividing by 100, in

order to determine the percentage of agreement. Mean agreement for Helen’s problem

behaviors was 89.03% (range, 81.67%-95%), and mean agreement for Vincent’s problem

behaviors was 95.29% (range, 91.67%-100%).

Preference Assessments

Two paired-choice preference assessments were conducted prior to the start of

treatment, following procedures described by Fisher et al. (1992). The first preference

assessment was used to identify moderately preferred leisure materials, and the second

assessment was used to identify moderately preferred academic tasks for each participant.

Prior to the leisure item preference assessment, several items and activities were

identified through interviews with parents and staff. During the assessment, two of these

leisure items were presented to the participant at a time, and the participant was prompted

to select one of the items. The participant was then allowed to manipulate the item for 2

min before being presented with another choice of two leisure items. Each leisure item

was paired with every other leisure item. Six items were included for Helen, for a total of

15 trials, and five items were included for Vincent, for a total of 10 trials. The number of

times each item was selected was divided by the total number of times the item was

presented to yield a percentage. Moderately preferred leisure items were identified as the

19

items that were selected between 30% and 80% of opportunities. The academic activity

preference assessment was identical to the leisure preference assessment, except that

academic tasks were presented, rather than leisure items.

Functional Analysis

To determine the function of the problem behaviors, a functional analysis was

conducted for each participant according to the procedures outlined by Iwata, Dorsey,

Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982/1994). Three conditions were included in the

functional analysis: attention, demand, and play. In the attention condition, the participant

and experimenter were in the participant’s bedroom, which contained a table, chairs, a

bed, shelves, and moderately preferred leisure and academic materials, as identified

during the preference assessments. The experimenter offered brief verbal interactions on

a FR 1 schedule when the target behavior occurred but otherwise ignored the participant.

In the demand condition, the experimenter presented the participant with academic tasks

similar to those typically presented in the school or in-home treatment program using a

least-to-most prompting hierarchy, and removed the task for 30 s contingent upon

occurrences of the target behavior. During the play condition, the experimenter delivered

positive statements to the participant on a fixed time (FT) 30-s schedule. In addition,

moderately preferred leisure and academic materials were continuously available and no

demands were placed on the participant throughout the session. Target behaviors were

ignored. Functional analysis sessions were 10 min in duration.

20

Experimental Design

A multielement combined with a reversal design was used to compare the effects

of pre-session exposure to reinforcement and pre-session no exposure to reinforcement

when implemented in conjunction with extinction. Pre-session exposure and pre-session

no-exposure conditions were conducted in an alternating fashion in order to demonstrate

that rates of behavior differ during conditions in which the MO is present (pre-session noexposure) versus absent (pre-session exposure). Following a return to baseline, the presession exposure condition was presented for an extended number of sessions, followed

by several sessions of the pre-session no-exposure condition, in an effort to determine

whether observed decreases in problem behavior maintained in the absence of the presession exposure procedure.

The baseline condition was identical to the attention condition of the functional

analysis. The participant and the experimenter were present in the participant’s bedroom

with a table, chairs, a bed, shelves and leisure materials. The experimenter presented the

participant with a brief reprimand (e.g., “I can’t talk right now”) contingent upon

occurrences of the target behavior (FR 1 schedule), and otherwise ignored the participant.

Baseline sessions were 10 min in duration.

During the pre-session exposure condition, attention was delivered prior to

treatment sessions. The pre-session exposure condition was identical to the play condition

of the functional analysis. For 15 min prior to the treatment session, the experimenter

delivered positive statements to the participant on a FT 30-s schedule; leisure materials

were continuously available; no demands were placed on the participant; and all

21

occurrences of the target behavior were ignored. When the treatment session began, the

experimenter made a brief statement to the participant (e.g., “It’s time for me to work

now; we’ll talk later”), and immediately stopped interacting with the participant.

Treatment sessions were 10 min in duration, during which the experimenter and the

participant remained in the room, with leisure materials available, but the experimenter

did not interact with the participant at all, and all occurrences of the target behavior were

ignored.

During the pre-session no exposure condition, the participant was prompted to

work or play independently for 15 min immediately prior to the treatment session, and

was provided with task and leisure materials during that time. Treatment sessions in this

phase were 10 min in duration, and were identical to those in the pre-session exposure

condition. The experimenter made a brief statement to the participant, and then did not

interact with the participant at all during the session.

22

Chapter 3

RESULTS

Preference Assessments

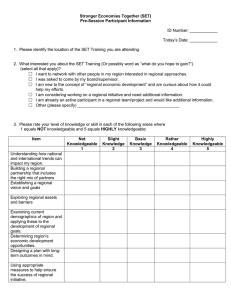

Results of the preference assessments for leisure and task materials for Helen are

depicted in Figure 1 (below).

Figure 1 Preference assessment results for Helen

Leisure Preference Assessment

Percentage of Intervals Selected

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Music Box

Helen

Nesting

Blocks

Keyboard

Play Lawn

Mower

Truck

Mr. Potato

Head

23

Task Preference Assessment

Percentage of Intervals Selected

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Helen

Sorting

Beads

Popsicle

Put-In

Puzzle

Coin Put-In Clothespin Piggy Bank

Pinch

Results indicated a moderate preference for the music box, nesting blocks, a keyboard, a

play lawn mower, a toy truck, and Mr. Potato Head. Results for task materials indicated a

moderate preference for a Popsicle stick put-in task, a puzzle, and a coin put-in task. The

identified moderately preferred leisure and task items were available to her throughout all

sessions of the experimental condition.

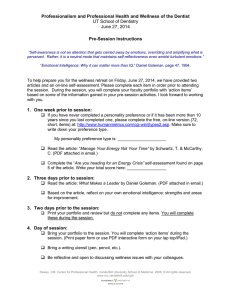

Results of the preference assessments for leisure and task materials for Vincent

are depicted in Figure 2 (below). Results for leisure materials showed that Vincent

demonstrated a moderate preference for a toy fire truck, puppets, and a picture book.

Results for task materials showed that Vincent demonstrated a moderate preference for a

marble put-in task, and a color-sorting task. The identified moderately preferred leisure

and task items were available to him throughout all sessions of the experimental

condition.

24

Figure 2 Preference assessment results for Vincent

Leisure Preference Assessment

Percentage of Intervals Selected

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Vincent

Kitchen

Toys

Fire Truck

Puppets

Picture

Books

Blocks

Wooden

Puzzle

Task Preference Assessment

100%

Percentage of Intervals Selected

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Tracing Pages Marble Put-in Color Sorting

Vincent

Matching

Wooden

Puzzles

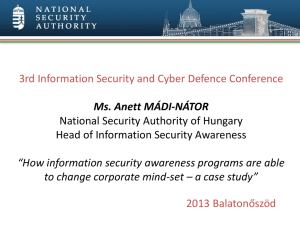

Functional Analysis

Functional analysis results are depicted in Figure 3 (below). For both participants,

target behaviors occurred almost exclusively in the attention condition (M = 36.25% of

25

intervals for Helen; M = 39.67% of intervals for Vincent), suggesting that target

behaviors for both participants were maintained by access to attention.

Figure 3 Functional analysis results for both participants

% of Intervals in which Bx Occurred

100%

90%

Attention

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

Control

30%

20%

Demand

10%

0%

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Session

Helen

8

9

10

11

12

% of Intervals in which Bx Occurred

100%

90%

80%

Attention

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

Control

Demand

20%

10%

0%

1

Vincent

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Session

10

11

12

13

14

15

26

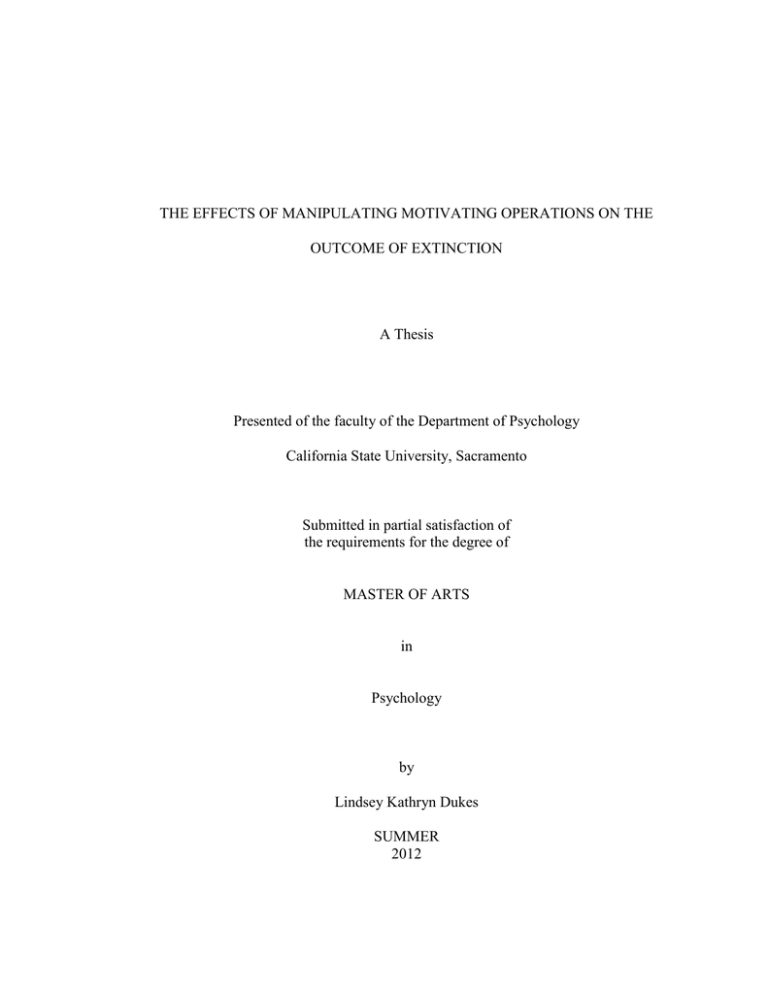

Experimental Conditions

Results for the experimental conditions for both participants are depicted in

Figure 4 below (results for Helen are depicted in the top panel and results for Vincent are

depicted in the bottom panel). Helen’s level of problem behavior during the initial

baseline condition was similar to that observed during the attention condition of the

functional analsis (M = 36.25% of intervals). During the multielement phase, Helen was

observed to emit problem behaviors during significantly more intervals during the presession no attention condition (M = 49.33%) than during the pre-session attention

condition (M = 23.33%). The level of responding during the pre-session no attention

condition was also higher than that observed during the initial baseline, while the level of

responding during the pre-session attention condition was lower than that observed

during the initial baseline. In the return to baseline condition, the level of target behaviors

was higher than that observed during the initial baseline condition (M = 46.25%).

Following this, the extended pre-session attention condition was implemented, during

which Helen emitted the target behavior in an average of 21.33% of intervals, which was

similar to the percentage observed during the pre-session attention condition in the

multielement phase. In the final condition of reversal to pre-session no attention, Helen’s

level of target behavior was initially higher than that observed during the previous

condition, but quickly decreased to a level similar to that observed during the pre-session

attention condition (M = 22.78%).

27

Figure 4 Intervention results for both participants

% of Intervals in Which Behavior Occurred

Baseline

100%

15 Min Presession

+ EXT

Baseline

15 Min Presession

Attention + EXT

90%

15 Min

Presession

No

Attention+

EXT

No Attention

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

Attention

30%

20%

10%

0%

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10111213141516171819202122232425262728293031323334

Session

Helen

15 Min

% of Intervals in Which Behavior Occurred

100% Baseline Presession + Baseline

EXT

90%

15 Min Presession

Attention + EXT

No

Attention

80%

15 Min

Presession

No Attention +

70%

60%

2 week family

vacation

50%

40%

30%

20%

Attention

10%

0%

1

Vincent

3

5

7

9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45

Session

28

Vincent’s level of problem behavior during the initial baseline condition was

similar to that observed during the attention condition of the functional analsis (M =

39.67% of intervals). During the multielement phase, Vincent was observed to emit

problem behaviors during significantly more intervals during the pre-session no attention

condition (M = 55%) than during the pre-session attention condition (M = 35%). In the

return to baseline condition, Vincent’s level of target behavior was similar to that

observed during the initial baseline condition (M = 36.25%). During the extended presession attention condition,Vincent’s level of target behaviors decreased steadily, (M =

25.28% of intervals), which was lower on average than that observed during the presession attention condition in the multielement phase. In the final condition of reversal to

pre-session no attention, Vincent’s level of target behavior was initially higher than that

observed during the previous condition, but steadily decreased to a level similar to that

observed during the extended pre-session attention condition (M = 27.67%).

29

Chapter 4

DISCUSSION

Results of this study replicate and extend those reported by O’Reilly and

Edrisinha et al. (2006), O’Reilly and Sigafoos et al. (2006), O’Reilly et al. (2007), and

Rispoli et al. (2011) on the use of pre-session exposure to reinforcers as an intervention

for addressing inappropriate behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement.

Similar to previous findings, results of the current study demonstrated that following presession exposure to a reinforcer participants’ rate of target behaviors was reduced when

compared to both the baseline rate and the rate of responding observed when no access to

the reinforcer was provided. These results suggest that for both participants,

noncontingent access to the maintaining reinforcer had abolishing and abative effects on

the MO for the problem behavior. This is consistent with the findings in previous studies.

However, as demonstrated by the increase in the target behavior observed for both

participants during the return to baseline condition, this antecedent-based intervention did

not produce lasting changes in behavior in the absence of continued pre-session exposure.

The current study also examined the effects of combining this antecedent-based

intervention with the extinction procedure, as has been recommended in some previous

research (see O’Reilly & Sigafoos et al., 2006). The pre-session attention condition

combined with extinction was implemented for an extended number of sessions, in an

effort to determine whether extinction would continue to be effective even when the MO

for responding was abolished and abated. For both participants, it was observed that

30

responding during the extended pre-session attention condition was decreased when

compared to baseline, but in both cases responding did continue to occur, although at a

reduced rate. When the participants were then exposed to the pre-session no attention +

EXT condition, both showed a brief increase in responding over the rate observed in the

previous condition, followed by a steady decrease in rate of responding to levels similar

to those observed in the pre-session attention + EXT condition. When comparing the rate

of target behaviors during the pre-session no attention + EXT condition from the

multielement phase with the rate observed during the second pre-session no attention +

EXT condition, it is clear that extinction occurred for both participants.

For Helen, responding was immediately reduced when pre-session attention +

EXT was implemented, and her rate of responding remained below baseline throughout

the extended pre-session attention + EXT condition. Upon reversal to the pre-session no

attention + EXT condition, responding temporarily increased to a rate slightly below that

observed during the initial pre-session no attention + EXT condition, but quickly

decreased to a rate slightly below that observed during the pre-session attention + Ext

condition. Comparison between the rate of responding during the first pre-session no

attention + EXT condition and the second clearly demonstrates that extinction did occur

for this participant during the extended pre-session + EXT condition, which suggests that

the pre-session exposure intervention may be effectively combined with the extinction

procedure to produce decreased responding during EXT while still producing lasting

changes in behavior.

31

For Vincent, responding remained near baseline levels when pre-session attention

+ EXT was initially implemented, but his rate of responding steadily decreased from

baseline to below baseline levels across the extended pre-session attention + EXT

condition. Upon reversal to the pre-session no attention + EXT condition, responding

temporarily increased to a rate similar to that observed during the initial pre-session no

attention + EXT condition, which was higher than the rate observed during baseline, but

then quickly decreased to a rate similar to that observed during the pre-session attention +

EXT condition. Based on the steady decrease in responding observed during the extended

pre-session attention + EXT condition, as well as the ultimate differences in rate of

responding between the first pre-session no attention + EXT condition and the second, it

appears that extinction did occur for this participant despite the abative and abolishing

effect of pre-session attention on the MO for the target behavior. With this participant, it

is also interesting to note that even with the inclusion of pre-session attention, the rate of

responding during the extended EXT condition was initially similar to that observed

during baseline, rather than showing an immediate reduction as has often been reported in

the research (see O’Reilly and Edrisinha et al., 2006, O’Reilly and Sigafoos et al., 2006,

O’Reilly et al., 2007, and Rispoli et al., 2011). However, it is clearly demonstrated during

the multielement condition that responding during the pre-session attention + EXT

condition was suppressed when compared to responding during the pre-session no

attention + EXT condition. This suggests that application of extinction alone, without

including pre-session exposure to the maintaining reinforcer, may have evoked a

temporary but significant increase in the rate of responding, or extinction burst, for this

32

participant. Following the reversal to pre-session no attention + EXT, indeed, a brief

increase in the rate of responding to a level slightly above baseline was observed, but this

rate decreased very quickly across sessions, which differs from the pattern observed

during the initial pre-session no attention + EXT condition. Application of the pre-session

exposure intervention combined with EXT likely resulted in a reduction in the intensity

and duration of the extinction burst for this participant, while still allowing the extinction

procedure to be effective in decreasing the rate of responding. This suggests that the presession exposure intervention may be especially useful when combined with extinction

when addressing problem behaviors for which an intense or sustained extinction burst

may result in significant injury or property damage.

Results of the present study suggest that EXT does continue to be an effective

intervention when combined with the pre-session exposure intervention, despite the

abolishing and abative effects that this procedure has on the MO for the target behavior.

In addition, these results suggest that there may be additional benefits in combining these

procedures. The rate of responding during the pre-session exposure + EXT condition may

be significantly decreased compared to the baseline rate, which would allow practitioners

to more easily implement extinction when addressing problem behaviors that may be

dangerous or otherwise very difficult to effectively extinguish in an applied setting. In

addition, even if the rate of responding during pre-session exposure + EXT is not below

that of baseline, it is likely that combining these procedures will help decrease the

intensity and duration of an extinction burst, which is especially important when

addressing injurious behaviors. Results of the current study suggest that the pre-session

33

exposure intervention may be a desirable addition to the EXT procedure, especially when

addressing extremely intense or injurious problem behaviors.

One limitation of the current study is the duration of the pre-session exposure

periods and the duration of treatment sessions. In this study, pre-session exposure or noexposure periods were 15 min in duration, while treatment sessions were only 10 min.

These relatively brief session durations limit the generalizability of this research to the

natural environment. The brief duration of the intervention sessions following pre-session

exposure/no-exposure conditions restricts researchers from identifying the effect this

procedure would have during longer intervals, and it may be theorized that as the presession exposure became more temporally distant, rates of the target behavior would

increase. In addition, the relatively long periods of access to the maintaining reinforcer or

deprivation from the maintaining reinforcer further restrict the application of this

procedure to the natural environment, in which individuals may not be able to provide

long periods of constant interaction, access to tangibles, or frequent snacks, or to

withhold these reinforcers for long periods of time. Also, no research to date has

investigated the effects of different quantities of the maintaining reinforcer on response

rate, and it is not clear whether 15 min is a necessary or optimal duration of time.

An additional limitation of the current study is the arbitrary selection of the

number of pre-session exposure + EXT sessions implemented during the extended

condition. For individuals such as Vincent who demonstrate a clear reduction in target

behavior across sessions, this limitation does not apply, and the number of sessions can

be guided by the observed rate of responding. However, for other individuals such as

34

Helen who demonstrate an immediate suppression in responding and for whom

responding remains low across sessions, it is difficult to determine the optimal number of

sessions to apply before reversing to the pre-session no-exposure + EXT condition. In the

current study, the number of sessions was arbitrarily selected, and appeared to be

effective for that participant; however, this number may vary across participants and may

be difficult to identify consistently when the rate of responding cannot be used as a guide.

Future research on the duration of pre-session exposure/no-exposure conditions

and session durations would provide insight into the viability of implementing shorter

pre-session periods and longer sessions, in order to increase the generalizability of this

procedure to the natural environment. One approach that may be beneficial is to

systematically manipulate the duration of pre-session periods while maintaining a

constant session duration, in order to specifically identify the effect of different durations

of pre-session exposure/no-exposure on rates of responding during sessions. This may

allow researchers to identify a mean pre-session duration that is typically effective for

most participants, although it is also possible that the duration of effective pre-session

exposure will be demonstrated to be highly variable across individuals. Additional

recommendations for future research include varying the number of pre-session exposure

+ EXT treatment sessions implemented prior to returning to pre-session no-exposure +

EXT, in order to determine the number of sessions necessary to successfully extinguish

the target behavior. This would facilitate implementation of this procedure in applied

settings, in which the satiation procedure may be difficult to implement consistently over

long periods of time. An additional possibility to identify the appropriate number of pre-

35

session exposure sessions for each individual is to introduce probe sessions, in which a

single pre-session no-exposure condition is introduced and rate of responding during this

session is observed. Future research may examine how to best determine based on these

data that the participant’s target behavior has been effectively reduced, since the rate of

responding during the initial return to pre-session no-exposure was observed to increase

for both of the current participants.

36

REFERENCES

Chandler, L. K. & Dahlquist, C. M. (2006). Functional assessment: Strategies to prevent

and remediate challenging behavior in school settings. 2nd Edition. New Jersey:

Pearson Prentice Hall.

Fisher, W., Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Hagopian, L. P., Owens, J. C., & Slevin, I.

(1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons

with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25,

491-498.

France, K. G. & Hudson, S. M. (1990). Behavior management of infant sleep

disturbance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23, 91-98.

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994).

Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 27, 197-209. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in

Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3-20, 1982)

Kahng, S., Hendrickson, D. J., & Vu, C. P. (2000). Comparison of single and multiple

functional communication training responses for the treatment of problem

behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 321-324.

Kahng, S., Iwata, B. A., Thompson, R. H., & Hanley, G. P. (2000). A method for

identifying satiation versus extinction effects under noncontingent reinforcement

schedules. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 419-432.

37

Laraway, S., Snycerski, S., Michael, J., & Poling, A. (2003). Motivating operations and

terms to describe them: some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 36, 407-414.

Lerman, D. C., Iwata, B. A., & Wallace, M. D. (1999). Side effects of extinction:

Prevalence of bursting and aggression during the treatment of self-injurious

behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32, 1-8.

Lindberg, J. S., Iwata, B. A., Roscoe, E. M., Worsdell, A. S., & Hanley, G. P. (2003).

Treatment efficacy of noncontingent reinforcement during brief and extended

application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 1-19.

Michael, J. M. (1982). Distinguishing between discriminative and motivational functions

of stimuli. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 37, 149-155.

Michael, J. L. (1993/2003). Concepts and Principles of Behavior Analysis. Revised

Edition. Kalamazoo, MI: Association for Behavior Analysis International.

Miltenberger, R. G. (2011). Behavior Modification Principles and Procedures. Belmont,

CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

O’Reilly, M. F., Edrisinha, C., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G., & Andrews, A. (2006).

Isolating the evocative and abative effects of an establishing operation on

challenging behavior. Behavioral Interventions, 21, 195-204.

O’Reilly, M., Edrisinha, C., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G., Cannella, H., Machalicek, W., &

Langthorne, P. (2007). Manipulating the evocative and abative effects of an

establishing operation: influences on challenging behavior during classroom

instruction. Behavioral Interventions, 22, 137-145.

38

O’Reilly, M. F., Lancioni, G. E., King, L., Lally, G., & Dhomhnaill, O. N. (2000). Using

brief assessments to evaluate aberrant behavior maintained by attention. Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 109-112.

O’Reilly, M. F., Sigafoos, J., Edrisinha, C., Lancioni, G., Cannela, H., Choi, H. Y., &

Barretto, A. (2006). A preliminary examination of the evocative effects of the

establishing operation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 239-242.

Piazza, C. C., Moes, D. R., & Fisher, W. W. (1996). Differential reinforcement of

alternative behavior and demand fading in the treatment of escape-maintained

destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 569-572.

Rapp, J. T. (2006). Toward an empirical method for identifying matched stimulation for

automatically reinforced behavior: a preliminary investigation. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 137-140.

Repp, A. C., & Deitz, S. M. (1974). Reducing aggressive and self-injurious behavior of

institutionalized retarded children through reinforcement of other behaviors.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7, 313-325.

Rispoli, M., O’Reilly, M., Lang, R., Machalicek, W., Davis, T., Lancioni, G., & Siafoos,

J. (2011). Effects of motivating operations on problem and academic behavior in

classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 187-192.

Roane, H. S., Fisher, W. W., Sgro, G. M., Falcomata, T. S., & Pabico R. R. (2004). An

alternative method of thinning reinforcer delivery during differential

reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 37, 213-218.

39

Shukla, S., & Albin, R. W. (1996). Effects of extinction alone and extinction plus

functional communication training on covariation of problem behaviors. Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 565-568.

Thompson, R. H., Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. C., & Kuhn, D. E. (1998). The evaluation

and treatment of aggression maintained by attention and automatic reinforcement.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31, 103-116.

Van Camp, C. M., Lerman, D. C., Kelley, M. E., Contrucci, S.A., & Vorndran, C. M.

(2000). Variable-time reinforcement schedules in the treatment of socially

maintained problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 545557.

Vollmer, T. R., Iwata, B. A., Zarcone, J. R., Smith, R. G., & Mazaleski, J. L. (1993). The

role of attention in attention-maintained self-injurious behavior: Noncontingent

reinforcement and differential reinforcement of other behavior. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 26, 9-21.

Wilder, D. A., & Carr, J. E. (1998). Recent advances in the modification of establishing

operations to reduce aberrant behavior. Behavioral Interventions, 13, 43-59.

Wilder, D. A., Masuda, A., O’Conner, C., & Baham, M. (2001). Brief functional

analysis and treatment of bizarre vocalizations in an adult with schizophrenia.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 34, 65-68.

40

Worsdell, A. S., Iwata, B. A., Hanley, G. P., Thompson, R. H., & Kahng, S. (2000).

Effects of continuous and intermittent reinforcement for problem behavior during

functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33,

167-179.