THE NEEDS OF FEMALE JUVENILE OFFENDERS Nancy Rocha

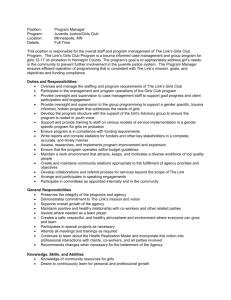

advertisement