AN EVALUATION OF THE HIGH-PROBABILTY INSTRUCTION SEQUENCE

advertisement

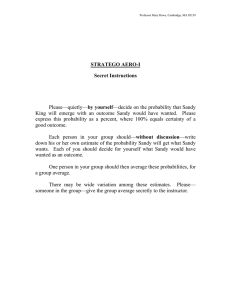

AN EVALUATION OF THE HIGH-PROBABILTY INSTRUCTION SEQUENCE WITH AND WITHOUT DEMAND FADING IN THE TREATMENT OF FOOD SELECTIVITY A Thesis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Psychology (Applied Behavior Analysis) by Diana Lynn Morgan SPRING 2014 AN EVALUATION OF THE HIGH-PROBABILTY INSTRUCTION SEQUENCE WITH AND WITHOUT DEMAND FADING IN THE TREATMENT OF FOOD SELECTIVITY A Thesis by Diana Lynn Morgan Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Becky Penrod , Ph.D __________________________________, Second Reader Rebecca Cameron, Ph.D _____________________________________, Third Reader Jill Young, Ph.D ____________________________ Date ii Student: Diana Lynn Morgan I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator___________________ Jianjian Qin, Ph.D Date Department of Psychology iii Abstract of AN EVALUATION OF THE HIGH-PROBABILTY INSTRUCTION SEQUENCE WITH AND WITHOUT DEMAND FADING IN THE TREATMENT OF FOOD SELECTIVITY by Diana Lynn Morgan The high-probability instructional sequence with and without demand fading has been used in the treatment of food refusal to establish consumption of non-preferred or novel foods. Previous research suggests that this may be an effective treatment in increasing consumption for children who engage in food refusal. The present study aimed to extend previous research by comparing the effectiveness of the high-p sequence alone (as described by Patel et. al) and when combined with demand fading (as described by Penrod et al.) with children who engage in active food refusal. A multi-element design was used to evaluate the relative effects of the high-p sequence with and without demand fading. Results indicated that both treatments were ineffective in establishing consumption. However, the high-p sequence combined with demand fading was effective in increasing behaviors closer to the terminal response. Implications and recommendations are discussed as they relate to increasing consumption. _______________________, Committee Chair Becky Penrod, Ph.D _______________________ Date iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank her thesis committee, Dr. Becky Penrod, Dr. Rebecca Cameron, and Dr. Jill Young for their efforts in the development and fulfillment of this research project. Specifically, the author would like to thank Dr. Becky Penrod for her ongoing support and dedication to the completion of this study. The experience I have gained in working with Dr. Penrod has been invaluable to my academic and professional development. In addition, I would like to express my appreciation and gratitude to all of the members of the Sacramento State Pediatric Behavior Research Lab. Their feedback, encouragement, and friendship have made this a process a memorable experience. I would like to express thanks to my research assistants, Kristin Griffith, Colleen Whelan, and Tim Howland for their continuous dedication and assistance with data collection and procedural implementation throughout this entire project. As a final note, I would to express much appreciation to my husband and family for their ongoing support and encouragement throughout this process. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………...v List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..ix List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………….x Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………….…..1 Demand Fading…………….………………………………………………..........3 High-Probability Instructional Sequences…..…………………..………………...5 2. METHOD ……………………………………………………………………..........11 Participants ………………………………………………………….……….......11 Setting and Materials.……………………………………………….……….......13 Experimental Design….….………………………………………………………14 Response Measurement and Data collection of the Dependent Variable….…….14 Independent Variable...…………………………….…………………………….14 Procedural Integrity.………………………………..…………………………....15 Interobserver Agreement...………………………………………………………15 Pre-treatment Preference Assessment..……………………………………….....16 Compliance Assessment and Probes...…………………………………………...20 Baseline Procedures...……………………………………………………………25 Instructional Procedures...………………………………………………………..26 vi 3. RESULTS ……………………………………………………………….…….........29 Evan….……………………………………………………….…………….........29 Sandy………………………...………………………………………………...…31 4. DISCUSSION ………………………………………………………..…….….…....35 Appendix A. Pre-treatment Parent Interview: Feeding…….………………………..…41 Appendix B. Pre-treatment Parent Interview: Behavior and Compliance.………….…42 Appendix C. Food Related Compliance Assessment Data Sheet….…………………..43 Appendix D. General Compliance Assessment Data Sheet….………………….…..…44 Appendix E. Baseline Data Sheet……….……………...……………………...……....45 Appendix F. Treatment Data Sheet …..……………………......……………………....46 References ………………………..……………………………………………………...47 vii LIST OF TABLES Tables Page 1. Results of Food Related Compliance Assessment…...…………..........................24 2. Demand Fading Low-p Instruction Steps…….…………………….....................28 viii LIST OF FIGURES Figures Page 1. Pre-treatment preference assessment results for Evan…………………...…….....18 2. Pre-treatment preference assessment results for Sandy………………………..…19 3. Second pre-treatment preference assessment results for Sandy……………...…...20 4. Results for Evan…………...………………………...…………………………...31 5. Results for Sandy.…………………………..……………………………………34 ix 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Feeding problems can occur in typically developing children as well as children with developmental disabilities. However, the prevalence of feeding problems is significantly higher for children with developmental disabilities (Ahearn, Kerwin, Eicher, Luken, 2001; Bachmeyer, 2009). Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are said to be at greater risk of developing feeding problems (Ahearn, Castine, Nault, & Green, 2001; Bandini et al., 2010; Schreck, Williams, & Smith, 2004). Among these feeding problems is food selectivity, which has been characterized as consumption of a limited variety of foods (Bandini et al.; Levin & Carr, 2001; Penrod, Gardella, & Fernand, 2012), which can occur by food group, texture, brand, color, etc. (Levin & Carr). Another characteristic of food selectivity is refusal of less-preferred and/or novel foods (Bandini et al.; Levin & Carr). Food selectivity is problematic because even though a child may consume enough of their preferred foods to maintain an appropriate weight, their limited diet is often associated with nutritional deficits, which may pose a health risk for the child (Bandini et al.; Kern & Marder, 1996; Luiselli, Ricciardi, & Gilligan, 2005; Penrod, Gardella, & Fernand). Research on food selectivity has suggested that it may be a form of noncompliance (Bachmeyer et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2003; Kern & Marder, 1996) and often includes inappropriate mealtime behavior (Bachmeyer et al.; Kern & Marder; Levin 2 & Carr, 2001). Research has found that although the etiology of food refusal behavior varies across children it is frequently developed and maintained by both positive and negative reinforcement contingencies (Bachmeyer et al.; Freeman & Piazza, 1998; Kern & Marder; Penrod, Gardella, & Fernand, 2012). Specifically, a child’s food refusal behavior may be negatively reinforced when the caregiver removes the food or terminates the meal in an effort to reduce or terminate the child’s inappropriate mealtime behavior. A child’s food refusal behavior may be positively reinforced in one of two ways: access to attention or tangible items. For example, a caregiver may provide attention in the form of coaxing the child to eat the food or vocal redirection of the child’s inappropriate mealtime behavior. Similarly, a caregiver may offer access to a toy or preferred food after the child has begun to engage in inappropriate mealtime behavior. Any of these scenarios establish a history of reinforcement for the parent and the child that may lead the caregiver to only present preferred foods to the child and no longer present novel or lesspreferred foods in order to avoid inappropriate mealtime behavior (Kern & Marder, 1996; Penrod, Gardella, & Fernand, 2012). Given that limited diets characteristic of food selectivity are associated with potential nutritional deficits and health risks, identification of effective treatment procedures is critical. Research in this area has shown that escape extinction procedures that terminate the previous reinforcement contingency between inappropriate mealtime behavior and removal of non-preferred/novel foods, are highly effective in increasing food acceptance and expanding the number of foods in one’s diet (Bachmeyer et al. 2009; 3 Freeman & Piazza, 1998; Najdowski et al., 2003; Penrod et al., 2010). Since the effectiveness of escape extinction procedures in decreasing food refusal behavior as well as increasing food acceptance has been well documented in the literature, it is commonly included as one component of treatment packages designed to address food selectivity (e.g., Bachmeyer et al; Freeman & Piazza; Najdowski et al.; Penrod et al.). However, although effective, escape extinction is a consequence-based procedure and is often associated with an initial increase in inappropriate mealtime behavior (Bachmeyer et al.; Dawson et al., 2003; Penrod et al.); to address this problem, researchers have turned their attention to antecedent-based interventions. Given that food selectivity has been conceptualized as a form of noncompliance (Dawson et al.), recent studies have explored the efficacy of antecedent-based interventions that have been shown to be effective in increasing compliance in other areas (Penrod et al., 2012), specifically, demand fading (or in this context bite fading) and the use of high-probability instructional sequences. Demand Fading Demand fading (e.g., bite fading) is one example of an antecedent-based intervention included as a component of treatment packages to address food selectivity (Penrod et al., 2010; Knox et al., 2012; Luiselli, 2000; Najdowski et al., 2003; Najdowski et al., 2010). Knox and colleagues implemented a treatment package including prompting, reinforcement, and bite fading to address food selectivity in an adolescent with autism. Bite fading was implemented by systematically increasing the number of bites the participant was required to consume prior to accessing reinforcement. This 4 procedure was effective in increasing consumption of less-preferred foods. Other studies utilizing bite fading as a component of treatment have had similar results, suggesting that bite fading (as part of a treatment package) is a valuable component in increasing consumption of less-preferred foods. However, when evaluating the independent effects of bite fading, research has shown that bite fading alone is not generally an effective treatment (Najdowski et al., 2003; Penrod et al., 2010). In 2010, Penrod and colleagues conducted a component analysis of various components that are often included in treatment packages for food selectivity. In this study researchers systematically evaluated the effectiveness of treatment components in 3 phases. Treatment components were sequentially introduced; in other words, one additional treatment component was added in each phase. A participant moved on to the next phase if the previous phase was shown to be ineffective in increasing food consumption. The different phases consisted of the following: baseline, which included differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (i.e., food consumption) and escape for refusal behaviors (DRA + escape); Phase 1- DRA + escape + bite fading; Phase 2 - DRA + escape + bite fading + reinforcer manipulation, in which the magnitude of reinforcement was increased; and Phase 3 - DRA + bite fading + reinforcer manipulation + escape extinction. For two participants, progression to Phase 3 was necessary in order to increase food consumption, and for one participant, food consumption increased in Phase 2 when the magnitude of reinforcement was increased. These results suggest that bite fading alone may not be sufficient to increase food consumption. Given these results, 5 recent research has continued to explore new strategies that may be effective in increasing food consumption without the need for escape extinction. High-Probability Instructional Sequences Behavioral momentum and the use of high-probability sequences is another antecedent-based intervention that has been studied and recently included as a primary treatment or as part of a treatment package to treat food refusal and food selectivity. The concept of behavioral momentum (derived from Newton’s law of motion), was first introduced by Nevin, Mandell, and Atak, in an experimental study with rats in 1983. This idea of behavioral momentum was applied to the treatment of noncompliance in adults with severe mental retardation in a study conducted by Mace and colleagues in 1988. Behavioral momentum has been defined as the tendency for behavior to persist following a change in environmental conditions with a positive correlation between response persistence and the rate of reinforcement (Mace et al.). The purpose of the Mace et al. study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a high-probability command sequence (high-p) in increasing compliance with low-probability (low-p) “do” and “don’t” commands. The high-p commands were instructions that each participant had demonstrated compliance with prior to beginning the study. A high-p command sequence was used to establish behavioral momentum prior to presenting a low-p command. The high-p command sequence consisted of three to four high-p instructions presented 10 s apart. Following compliance with the high-p sequence a low-p command was presented. The researchers hypothesized that presentation of the high-p command sequence would 6 establish a momentum in responding that would increase the likelihood of the participant responding to the low-p commands after contacting reinforcement for compliance with high-p commands. Results demonstrated that the high-p sequence was effective in increasing compliance to low-commands as well as decreasing the latency to complete low-p commands. Results of the study conducted by Mace and colleagues (1988) had significant implications for future research and treatment of noncompliant behavior. Much research has been done since 1988 that has explored the use of behavioral momentum and highprobability sequences to increase compliance across many different response topographies in academic and classroom settings (Belfiore, Basile, & Lee, 2008; Belfiore, Lee, Scheeler, & Klein, 2002; Belfiore, Lee, Vargas, & Skinner, 1997; Lee, Belfiore, Scheeler, Hua, & Smith; 2004; Lee & Laspe, 2003). In all of these studies the high-p and low-p responses were topographically similar. For example, participants were presented with three easy math problems prior to one difficult problem or participants were asked to write three single words prior to being presented with an open ended writing task (Belfiore, Lee, Vargas, & Skinner; Lee & Laspe). Recent research has begun to explore the use of high-p sequences to decrease food selectivity, characterized as noncompliance. Dawson and colleagues in 2003 evaluated the effectiveness of a high-p sequence with and without the use of an escape extinction procedure to increase food acceptance in a 3-year-old girl who engaged in active food refusal behavior (i.e., food refusal that co-occurs with other problem 7 behaviors). In contrast to earlier research, in this study, the high-p instructions were topographically different (one-step instructions that were not food related) from the low-p instruction (“take a bite”). Results demonstrated that the high-p sequence was only effective when combined with escape-extinction. It is possible that the reinforcement provided for compliance with high-p instructions was not sufficient to establish compliance with low-p instructions due to the instructions being topographically dissimilar. Patel and colleagues (2007) conducted a similar study to that of Dawson et al. (2003); however, Patel and colleagues used high-p instructions that were topographically similar (“take a bite” with presentation of an empty spoon) to the low-p instructions (“take a bite” with the presentation of the non-preferred food on the spoon). Also, the participant in this study engaged in passive food refusal (defined as noncompliance with demands to eat non-preferred foods in the absence of problem behavior) rather than active food refusal demonstrated by the participant in the study conducted by Dawson and colleagues. Results demonstrated that the high-p sequence was effective in increasing bite acceptance without the use of an escape extinction procedure. Results of the study conducted by Patel and colleagues may have been due to the use of topographically similar high-p instructions, as opposed to the topographically different high-p instructions used by Dawson and colleagues. However, the successfulness of the procedure could also be related to the type of food refusal that the participant displayed. It is unknown whether the procedure would be equally effective with a participant with active food refusal. 8 Penrod, Gardella, and Fernand (2012) further evaluated and extended the research on the use of a high-p sequence in the treatment of food selectivity by combing the high-p sequence with demand fading to address food selectivity in two boys with autism who displayed active food refusal. In this study the researchers used a high-p sequence that was topographically different (but still food related) from the low-p instruction combined with a demand fading procedure in which the difficulty of the low-p instruction was systematically increased until the terminal response of consuming the bite of food was achieved. The high-p instruction consisted of two instructions that the participant had previously demonstrated compliance with (e.g., smelling the food and licking the food). The low-p instruction was the next instruction in the demand fading sequence, or the next approximation to the terminal response requirement (e.g., balancing the food on the tongue). The high-p and low-p instructions shifted throughout the experiment as the demands increased, working up to the terminal low-p instruction to “take a bite” of the non-preferred food. Once compliance was achieved with a given low-p instruction (e.g., balancing the food on the tongue) that instruction then became part of the high-p sequence and a new low-p instruction was introduced (e.g., bite the food into two pieces). These procedures were effective in increasing consumption of non-preferred foods for both participants, thus providing further support that food selectivity can be addressed without the use of escape extinction procedures. Results of the study conducted by Penrod et al. (2012) demonstrated that topographically different high-p and low-p instructions were effective in treating food 9 selectivity; however, unlike the study conducted by Dawson et al. (2003), the high-p instructions were food related whereas those used by Dawson et al. were completely unrelated to food or eating. In both the study conducted by Dawson et al. and Penrod et al. participants engaged in active food refusal behavior; the difference between these two studies was the nature of the high-p instructions (as previously described) and in Penrod et al., the high-p instructional sequence was combined with demand fading, thus it is possible that food consumption increased as a result of the demand fading component; recall that in the Dawson et al. study, the high-p instructional procedure was not found to be effective. In the study conducted by Patel et al., the participant engaged in passive food refusal; in this study the high-p instructional sequence was found to be effective and it was suggested that one possibility for the difference between this study and Dawson et al. was that the participant in Dawson et al. engaged in active food refusal behavior as opposed to passive food refusal. Given the differences across these three studies, the conditions under which a high-p instructional sequence is likely to be effective in increasing food consumption are not clear. Thus, the present study aimed to extend previous research by comparing the effectiveness of the high-p instructional sequence alone (as described by Patel et. al) and when combined with demand fading (as described by Penrod et al.) with children who engage in active food refusal. Based on the previous research utilizing high-p instructional sequences to treat food refusal behavior it was expected that the high-p instructional sequence combined with demand fading would be more effective than the high-p instructional sequence alone 10 when treating food selectivity in children who display active versus passive food refusal behavior. 11 Chapter 2 METHOD Participants One girl diagnosed with autism and one typically developing boy participated in the study. Participants were selected based on referrals from local agencies in the community. The children selected as participants in the study were required to have an imitative repertoire (i.e., the ability to copy or follow the actions of another person), and basic listener silks (e.g., the ability to follow one-step instructions). Other criteria for inclusion in the study included resistance to trying novel foods (active food refusal) and a restricted diet within at least one of the following food groups: fruits, vegetables, protein, dairy, or starch. In order to determine if a participant was appropriate for this study, parents were interviewed by the researcher and asked to provide information regarding the child’s previous and current diet (See Appendix A). Parents were asked to identify 6 foods that the child did not prefer from one or more of the food groups listed above as well as 6 highly preferred foods. Additionally parents were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding information about the child’s overall behavior and compliance (See Appendix B). Evan was a 2.8 year old boy with a history of food selectivity. At the start of the study Evan’s parents reported that he primarily consumed chocolate donuts or French toast sticks for breakfast and a cheese quesadilla or Nutella sandwich for lunch and 12 dinner. Additionally, Evan consumed milk with all meals and ate a variety of carb-based snacks (e.g., gold fish, veggie sticks, and crackers) and chocolate (e.g., M&Ms and Oreos). His parents reported that mealtime was a “high anxiety event” and that Evan refused to sit at the table during mealtime and engaged in tantrum behaviors and gagging when asked to try new or non-preferred foods. Evan was referred by his pediatrician to a Speech Pathologist in August 2013, due to parent concerns regarding his limited diet and food selectivity. At the recommendation of the Speech Pathologist Evan’s parents tried several strategies to increase his participation in mealtimes and consumption of new foods by presenting meals at a child-sized table and encouraging Evan to simply touch or play with new foods; however, these strategies were not successful in increasing his consumption of new foods. Evan never had any exposure to or experience with the use of demand fading or high probability instructional sequences. Sandy was a 7.11 year old girl with a diagnosis of autism. Sandy received inhome early intensive behavioral treatment (EIBT) since age three. Sandy was enrolled in a 3rd grade special day class and discontinued her participation in the EIBT program approximately one month into the study. At the start of the study Sandy’s mother reported that she primarily ate goldfish as all or part of each meal during the day and only drank water or root beer. Additionally her mother reported that for lunch Sandy ate 2 bags of fruit snacks (brand specific), 2 vanilla cupcakes without frosting purchased only from Walmart, and sometimes would eat pancakes. Soon after beginning the study, Sandy’s mother reported that she had begun giving Sandy Pediasure daily per the 13 doctor’s recommendation and that with some persistence Sandy would drink it. During mealtimes, her mother reported that Sandy would sit with the family but would not eat the foods presented to her. When instructed to try new or non-preferred foods it was reported that Sandy would push the food away and would begin to gag and engage in tantrums if the food was not removed. Sandy’s mother reported that she had tried restricting access to goldfish in an attempt to get Sandy to eat other foods; however Sandy refused to consume other foods and she began to lose weight so the goldfish were reintroduced in order to maintain Sandy’s weight. During participation in the EIBT program the provider attempted to establish consumption of string cheese using a “first…then” contingency (i.e., first eat the string cheese and then you can have root beer”); however, Sandy’s mother reported that this strategy was not effective and after 6 months was discontinued because Sandy never put the cheese in her mouth. Setting and Materials Baseline and training sessions were conducted in the Pediatric Behavior Research Laboratory at California State University, Sacramento. The materials used for feeding sessions included a table with two chairs, preferred and non-preferred foods, plates, napkins, and utensils. Basic data collection materials included paper data sheets, a clipboard, pens, and a digital video camera. Two to five consecutive feeding sessions (i.e., alternating baseline, treatment I, and treatment II sessions described below), with 5 min breaks between each session were conducted each day with the total duration of sessions each day not exceeding 60 14 minutes. Sessions were trial based, thus the duration of each session varied. Sessions were conducted one to two times per week. All basic session procedures were followed as described by Penrod, Gardella, and Fernand (2012). Experimental Design A multi-element design was used to evaluate the relative effects of the high-p instructional sequence with and without demand fading. Response Measurement and Data Collection of the Dependent Variable Data were collected using paper and pencil data sheets throughout each session. Each session was also recorded via a video camera and later coded for interobserver agreement purposes. The dependent variable included the percentage of bites consumed following the presentation of the low-p instruction as well as percentage of compliance with low-p instructions. Bite consumption was defined as accepting the food followed by a clean mouth check and compliance was defined as following a given instruction after the initial presentation or prompt (described below). Independent Variable The independent variable included delivery of two high-p instructions to take a bite of an empty spoon (treatment I described below) or two high-p instructions requiring contact with the target food that were considered approximations to the terminal response of bite consumption (treatment II described below), followed by a low-p instruction to take a bite of the non-preferred food (treatment I) or a low-p instruction to engage in the next demand fading step (treatment II) as well as contingent delivery of social praise (for 15 Evan) or social praise and tickles (for Sandy) for compliance with high-p instructions, and high-preferred edibles plus social praise for compliance with low-p instructions. The goal of treatment was to increase compliance with instructions closer to the terminal response and to establish consumption of new or non-preferred foods. Procedural Integrity Two independent observers collected procedural integrity data on all trials for therapist prompting and delivery of the appropriate reinforcer. Procedural integrity data were calculated as the total number of correct implementations divided by the total number of correct and incorrect implementations and then multiplied by 100 for a percentage of correct implementations. Procedural integrity data were collected for 90% of sessions for Evan and 93% of sessions for Sandy. Procedural integrity data for prompting averaged 99.4% (90-100%) for Evan and 99.3% (80-100%) for Sandy. Procedural integrity data for delivery of the appropriate reinforcer averaged 99.4% (90100%) for Evan and 99.3% (90-100%) for Sandy. Interobserver Agreement Two independent observers collected interobserver agreement (IOA) data for bites consumed, compliance with low-p instructions, and procedural integrity. IOA for compliance and consumption was assessed on100% of Evan’s sessions and 100% of Sandy’s sessions. IOA for procedural integrity was calculated on 88% of sessions for Evan and 83% of sessions for Sandy. IOA was calculated using point-by-point agreement, and reported as a percentage by dividing the number of agreements by the 16 total number of trials and then multiplying by 100. An agreement for consumption or compliance was scored when both observers scored either the occurrence or nonoccurrence of behavior. An agreement for procedural integrity was scored when both observers scored either a plus (+) for correct implementation or a minus (-) for incorrect implementation of prompting or reinforcer delivery; observers had to agree on both measures in order for the trial to count as an agreement. IOA for Evan was 100% for compliance to low-p instructions, 100% for bites consumed, and 99.1% for procedural integrity. IOA for Sandy was 99.8% for compliance to low-p instructions, 100% for bites consumed, and 99.9% for procedural integrity. Pre-treatment Preference Assessment A paired-choice preference assessment was conducted prior to the start of the study to ensure that all non-preferred food items identified by parents were truly nonpreferred and to identify participants’ relative preference for high-preferred foods that could be delivered as reinforcement for consumption of non-preferred/novel foods and compliance with low-p instructions (a total of six non-preferred and six highly preferred food items). Paired-choice preference assessment procedures were followed as outlined by Fisher et al. (1992). Prior to beginning the preference assessment each participant was prompted to sample each of the food items. The food items were then presented in pairs until each food was presented in a pair with every other food item. The food selections were then scored and reported as a percentage of trials selected and consumed (number of trials the food was selected and consumed divided by total number of presentations and 17 then multiplied by 100). The foods were then rank ordered and three (for Evan) or six (for Sandy) of the foods consumed at zero percent were then used in the compliance assessment. Additionally the top three foods selected during 80% or more trials were then used as reinforcers throughout the study. Parents were asked to restrict access to the food items identified as highly preferred. For both participants, none of the non-preferred/new foods were consumed during the preference assessment. Figure 1 depicts results of the preference assessment for Evan and Sandy. For Sandy, none of the foods identified as highly preferred by her mother were chosen at the specified criteria of 80% or above. Therefore, a second preference assessment was conducted using the three preferred foods that she selected and consumed during the initial preference assessment as well as two social activities (i.e., high-5s and tickles) selected by the researcher based on observation during rapport building with the researcher prior to the first preference assessment as well as from parent report of Sandy’s preferences. Since the social activities were not tangible, they were represented by colored circles (i.e., tickles was represented by a blue circle and high-5s was represented by a red circle), and were taught prior to the second preference assessment. The association of the colored circles with the corresponding social activity was taught by presenting a colored circle and prompting Sandy to touch the circle, which was immediately followed by delivery of the corresponding social activity for approximately 15 seconds. This procedure was repeated until Sandy consistently touched the presented colored circle each time it was placed in front of her. Following the second preference 18 assessment the foods and activities were rank ordered and the top two items selected during 60% or more trials were then used as reinforcers throughout the study. Figure 3 depicts the second preference assessment results for Sandy. Figure 1. Pre-treatment preference assessment results for Evan. Pretreatment preference assessment results for Evan contained six non-preferred and six highly preferred edibles. M&Ms, goldfish, and Oreos were the most highly-preferred edibles with all selected during 80% or more of trials and thus were used as reinforcers throughout the study. All other foods were selected during 0% of trials. 19 Figure 1. Pre-treatment preference assessment results for Sandy. Pretreatment preference assessment results for Sandy contained six non-preferred and six highly preferred edibles. Soft cookie, root beer, and cupcake were the most frequently consumed edibles; however, none were considered highly preferred as they were each selected during less than 40% of trials. All other foods were selected during 0% of trials. 20 Figure 3. Second pre-treatment preference assessment results for Sandy. Second pretreatment preference assessment results for Sandy using the top three most preferred edibles from the first preference assessment as well as two social activities selected by the researcher. Tickles and root beer were the top two highest preferred activities/edibles and were thus used as reinforcers throughout the study. Compliance Assessments and Probes Two compliance assessments were conducted prior to the start of the study. The first compliance assessment was conducted using the foods to be included in the baseline 21 and treatment procedures and the second compliance assessment was conducted using non-food related instructions. Food Related Compliance Assessment The food related compliance assessment was conducted in order to demonstrate that acceptance of an empty spoon was a high-p response as well as to probe compliance with each of the demand fading steps to ensure that the instructions that would be presented as high-p instructions were in fact instructions for which the child demonstrated compliance with. This assessment also ensured that foods used in each of the baseline and treatment conditions were similar in relation to the participant’s compliance with each. Table 1 depicts results of the initial compliance assessments for Evan and Sandy. Additionally, a compliance assessment was conducted for the treatment II food following mastery of a given low-p demand fading step. This compliance assessment probe was conducted in order to identify if any generalization had occurred and to determine if it was necessary to continue with the demand fading sequence as outlined or if it was possible to skip a step. Acceptance of an empty spoon as well as all demand fading steps were assessed once with three to six foods consumed during 0% of trials in the preference assessment. Each session began with one presentation of an empty spoon followed by one trial of each of the demand fading steps. A trial consisted of an empty spoon or single bite of food presented in front of the child and the therapist stating the instruction for the given demand fading step (e.g., 22 “Touch the apple” or “Smell the apple”) plus a model of the desired response. If the child did not engage in the target response within 5 s, an additional vocal plus model prompt was delivered (“Copy me” or “Do what I’m doing” while the researcher modeled the behavior) and the food remained present for an additional 5 s. If the child did not imitate the researcher, the bite of food was removed and that trial was then terminated. The next trial was presented approximately 20 s following the end of the previous trial. Any food refusal or inappropriate mealtime behavior was ignored. Food refusal behaviors were defined as vocally refusing the food upon presentation (e.g., “No” or “I don’t like it”) or non-vocally refusing the food (e.g., gagging, pushing the food away, spitting out the food, or vomiting). Compliance resulted in brief verbal praise. For Evan, three foods that were consumed during 0% of trials during the preference assessment were used in the compliance assessments (foods included apple, hotdog, and corn). During the first compliance assessment (apple), Evan complied with 60% of trials. However, during the second (hotdog) and third (corn) compliance assessments Evan complied with 20% and 10% of trials, respectively. Due to the decrease in performance a fourth compliance assessment with apple was conducted on the same day to assess for consistency of performance across foods; Evan complied with 10% of trials. As a result of Evan’s decreasing compliance across foods on a given day, the researcher conducted a second compliance assessment with all three foods on a different day to attempt to identify a pattern in Evan’s compliance across the three foods. During compliance assessments five (hot dog), six (corn), and seven (apple) Evan 23 complied with 30%, 10%, and 10% of trials, respectively. This second set of compliance assessments allowed the researcher to identify that Evan wasn’t necessarily more compliant with one food more than another, but more so demonstrated decreases in compliance following the initial compliance assessment of each day. Given the observed pattern and inconsistent compliance it was decided that for treatment II (described below) the starting demand fading step for the low-p instruction was holding the food in order to establish consistent compliance across foods and sessions. For Sandy, three foods that were consumed during 0% of trials during the preference assessment were used in the first compliance assessments (foods included tomato, macaroni and cheese, and string cheese). During the first set of compliance assessments Sandy complied with 10%, 20%, and 50% (tomato, macaroni and cheese, and string cheese respectively) of trials. Given that the percentage of compliance with the string cheese was higher than the other two foods, a second set of compliance assessments was conducted with three additional foods that were consumed during 0% of trials during the preference assessment (foods included pizza, peanut butter sandwich, and apple). During the second set of compliance assessments Sandy complied with 50%, 30%, and 60% (pizza, peanut butter sandwich, and apple respectively) of trials. After a review of Sandy’s compliance with the six different foods, string cheese, pizza, and apple were selected based on Sandy’s similar compliance with each of those foods. Additionally, given that Sandy licked each of the selected foods during the compliance 24 assessments, the starting demand fading step for the low-p instruction was holding the food on her tongue. Table 1 Results of Food Related Compliance Assessment Evan Sandy #1 (apple) 60% #1 (tomato) 10% #2 (hot dog) 20% #2 (macaroni and cheese) 20% #3 (corn) 10% #3 (string cheese) 50% #4 (apple) 10% #4 (pizza) 50% #5 (hot dog) 30% #5 (peanut butter 30% sandwich) #6 (corn) 10% #7 (apple) 10% #6 (apple) 60% Note. Results represent percentage of compliance with demand fading steps during each compliance assessment. General Compliance Assessment A general compliance assessment was conducted in order to assess each participant’s level of compliance with general instructions given by a parent. For this assessment the parent of each participant was asked to present 5 one-step imitation actions and 5 one-step simple instructions (See Appendix D). While parents interacted with their child the researcher observed from approximately 10 feet away and recorded 25 the number of times that each instruction or action was presented as well as the participants’ response to given instructions or imitation actions. Evan complied with 90% of given instructions and 80% of imitation actions. Sidney complied with 80% of given instructions and 100% of imitation actions. The rationale for the general compliance assessment was to determine if noncompliance occurred across activities or if it was specific to feeding, as this information may be useful in predicting responsiveness to treatment. Baseline Procedures During an initial baseline, the foods to be used in the treatment phases (Treatment I: high-p alone and Treatment II: high-p plus demand fading) and food to be used during a continuous baseline condition were alternated. Each baseline session consisted of 10 trials. Each condition was associated with a different therapist (treatment I with therapist 1, treatment II with therapist 2, and baseline with therapist 3). Noncontingent access to 1 small bite of high-preferred food (for Evan) or 1 drink of high-preferred beverage (for Sandy) was provided at the beginning of each baseline session in order to establish a motivating operation. A trial consisted of a single bite of food presented in front of the child and the therapist stating, “Take a bite” while modeling the target behavior (i.e., consuming a bite of food). If the child did not consume the food within 5 s, a vocal plus model prompt was delivered (“Take a bite” while the researcher modeled the behavior). If the child still did not comply with the instruction, the bite of food was removed and that trial was terminated. The next trial was presented 26 approximately 20 s following the end of the previous trial. Any food refusal or other inappropriate mealtime behavior was ignored. Food refusal behaviors were defined as vocally refusing the food upon presentation of the food (e.g., “No” or “I don’t like it”) or non-vocally refusing the food (e.g., gagging, pushing the food away, spitting out the food, or turning away from the food). Verbal praise plus high-preferred food (i.e., M&Ms, Oreos, or goldfish for Evan) or 1 drink of the high-preferred beverage (i.e., root beer for Sandy) was delivered contingent on consumption following the initial instruction or prompt. Instructional Procedures Two instructional treatments were utilized during the treatment phase. Treatment I used the same high-p and low-p sequences as those used by Patel et al. (2007). Treatment II used the same high-p and low-p instructions and demand fading steps as those used by Penrod et al. (2012). The first instructional treatment (I) included a set of two high-p instructions followed by a low-p instruction within the same response class as the high-p instruction. For this phase the high-p instruction consisted of the presentation of an empty spoon and the low-p instruction was the presentation of a bite of the nonpreferred food. The second instructional treatment (II) included two high-p instructions made up of the two previously mastered demand fading steps followed by a low-p instruction which was the next demand fading step that the participant had not mastered. Table 2 depicts the demand fading steps and instructions associated with each. All 27 instructions during treatment II were performed with the non-preferred food (e.g., “Smell the chicken, kiss the chicken, lick the chicken”). For both instructional treatments, a given step met mastery criteria following two consecutive sessions of 100% compliance with the high-p and low-p instructions in the absence of refusal behavior. Following mastery of a given demand fading step in treatment II, a compliance assessment of all demand fading steps (as previously described above) was completed with the treatment II food. If the participant complied with the next step in the demand fading sequence then that step would be considered mastered and included in the high-p sequence and the next step in the demand fading sequence would be used as the next low-p instruction. This procedure was attempted for both participants; however, when a demand step was skipped, and not formally targeted as a low-p instruction, both participants demonstrated significant decreases in compliance with the low-p instruction. Thus it was determined that for both participants the demand fading sequence would be followed as outlined regardless of performance in the compliance assessment probes. Noncontingent access to 1 small bite of high-preferred food (for Evan) or 1 drink of high-preferred beverage and 10-15 seconds access to a high-preferred social activity was provided at the beginning of each treatment session in order to establish a motivating operation. Specifically, the participant was allowed to sample the designated reinforcer to increase motivation to comply with low-p instructions in order to gain additional access to the reinforcer. A trial consisted of a single bite of food or empty spoon presented in 28 front of the child and the therapist stating, “Take a bite” or other instruction related to the given demand fading step for treatment II (e.g., “Touch the food” or “Hold the food”) plus a model of the desired response. Prompting procedures and problem behavior were addressed in the same manner as in baseline. Compliance with the high-p instructions resulted in verbal praise (for Evan) or verbal praise plus social activity (i.e., tickles for Sandy) and compliance with the low-p instruction result in praise plus 1 small bite of the high-preferred food (i.e., M&Ms, Oreos, or goldfish for Evan) or 1 drink of the highpreferred beverage (i.e., root beer for Sandy). Table 2 Demand Fading Low-p Instruction Steps Demand Fading Step Instruction 1 “Touch the (food)” 2 “Hold the (food)” 3 “Smell the (food)” 4 “Kiss the (food)” 5 “Lick the (food)” 6 “Hold the (food) on your tongue” “Put the (food) in your mouth” “Chew the (food)” 7 8 9 “Take a bite” (final step) Note. Demand fading steps were based on those used by Penrod et al (2012). 29 Chapter 3 RESULTS Evan Figure 4 depicts the percentage of compliance with low-p instructions throughout the study. During the baseline sessions, none of the foods were ever consumed. During treatment I compliance with the low-p instruction occurred during 0% of trials. Treatment II was effective in increasing behaviors closer to the terminal response of food consumption, although consumption of the non-preferred food did not occur. In treatment II holding the food was the first low-p instruction with touching the food serving as both of the high-p instructions. Mastery for holding the food was reached in three sessions, following which a compliance assessment probe was conducted for all treatment steps. Results of the compliance assessment showed that Evan complied with steps up to and including licking the food; thus the low-p instruction for the next phase of treatment II was holding the food on his tongue for 3 seconds, with kissing the food and licking the food as the two high-p instructions. During the first session with this sequence (session 16) Evan complied with both high-p and low-p instructions for the first three trials, he then complied with the high-p instruction only, for trial five and six, and then engaged in refusal behavior and did not comply with high-p or low-p instructions for trials seven through ten. During the next session of treatment II (session 19) Evan engaged in refusal behavior for all trials and did not comply with high-p or low-p instructions. Following 30 this session, the high-p and low-p instructions were modified to reestablish compliance with high-p and low-p instructions; the modified low-p instruction was to kiss the food, with the high-p instructions being to hold the food and smell the food. Compliance with the modified instructions (session 21) immediately increased to 100%. Researchers continued to conduct compliance assessment probes following mastery of each treatment II low-p demand fading step; however the demand fading sequence was followed in order, regardless of Evan’s performance given his previous regression when demand fading steps were skipped. Following mastery of the low-p instruction to kiss the food in two sessions, Evan also mastered licking the food in two sessions. For the next low-p instruction to hold the food on his tongue, the first score was 90% (session 36) followed by a score of 100% (session 39). Following session 40, Evan’s parents made the decision to discontinue sessions due to personal family circumstances which prevented researchers from continuing through the remaining demand fading steps leading to the terminal response. Consumption did not occur during any trials for treatment or baseline foods during the study. 31 Figure 4. Results for Evan. Percentage of compliance with low-p instructions that occurred during the baseline and treatment conditions. Sandy Figure 5 depicts the percentage of compliance with low-p instructions throughout the study. During the baseline sessions, none of the foods were ever consumed. During all treatment I trials, compliance with the low-p instruction to take a bite of the food never occurred. Treatment II was effective in increasing behaviors closer to the terminal response of food consumption, although consumption of the non-preferred food did not occur. In treatment II holding the food on her tongue for three seconds was the first low-p instruction with kissing the food and licking the food serving as the high-p instructions. 32 During the first treatment II session, Sandy complied with high-p and low-p instructions during 0% of trials; additionally, Sandy complied with the high-p instructions 0% of trials during the first treatment I session as well. Given the significant change in Sandy’s performance from the initial pre-treatment compliance assessment one remedial session was conducted to reestablish consistent acceptance of the empty spoon. During the remedial training session, an empty spoon was presented on the plate with no other foods present; the high-p instruction was to touch the spoon with the low-p instruction to take a bite of the empty spoon. Compliance with high-p instructions resulted in verbal praise and compliance with the low-p instruction resulted in delivery of moderately preferred social activities (i.e., wiggly arms and high-5s). Following remedial training, compliance with high-p instructions during treatment I increased to 100%; specifically, she accepted the empty spoon. Additionally the low-p instruction for treatment II was modified to hold the food, with touching the food serving as both high-p instructions. Compliance with the low-p instructions for the following two treatment II session (sessions 13 and 16) remained at 0%. Following session 16, a modified prompting procedure was added and reinforcement was delivered for compliance with high-p and low-p instructions (tickles and root beer, respectively) for both treatment conditions. The assignment of reinforcers to high-p and low-p instructions was based on anecdotal observation of Sandy’s preference during previous sessions. The modified prompting procedure was as follows: following two vocal plus model instructions, if compliance did not occur within five seconds, Sandy was physically prompted to engage in the target behavior (the therapist 33 hand over hand guided Sandy to engage in the target behavior). For treatment I the physical prompt consisted of touching the food to her lips. This prompt procedure was implemented for both treatment conditions in order to maintain consistency across conditions and avoid any confounds. After the implementation of the modified prompt procedure and reinforcement for high-p sequences, compliance with low-p instructions in treatment II increased to 90% or higher for all demand fading steps up to holding the food on her tongue (sessions 19 through 55). Upon introduction of the low-p instruction to hold the food on her tongue for three seconds, compliance with low-p instructions dropped to 0%. Given this significant decrease in performance, during the next session of treatment II the low-p instruction was reduced to holding the food on her tongue for one second, following which compliance increased to 70%. Consumption did not occur during any trials for treatment or baseline foods during the study. 34 Figure 5. Results for Sandy. Percentage of compliance with low-p instructions that occurred during the baseline and treatment conditions. 35 Chapter 4 DISCUSSION The present study sought to evaluate the effects of high-p instructional sequences with and without demand fading in increasing consumption of non-preferred foods in two children with food selectivity; in specific, the high-p instructional sequence described by Patel et al. (2007) was compared to the high-p instructional sequence combined with demand fading, as described by Penrod et al. (2012). Results of the present study demonstrated that neither the high-p sequence alone or in combination with demand fading was effective in increasing consumption of non-preferred foods for both participants. Although consumption was not achieved in treatment II (high-p sequence combined with demand fading) for either participant, treatment II successfully increased behavior closer to the terminal response of consumption thus extending the previous research conducted by Penrod and colleagues. These results suggest that the demand fading sequence may have been the critical component responsible for the increased consumption observed in the Penrod et al. study with children with active refusal behavior; however, because consumption was not achieved in this study, this conclusion remains speculative. Future research should further examine the critical component in increasing consumption; specifically evaluating if the high-p instructional sequence is necessary or if demand fading alone would be sufficient to establish consumption of nonpreferred foods. 36 Although the high-p sequence combined with demand fading was not successful in establishing consumption of the target food, it may still be a useful procedure. Specifically, parents could be taught to implement this procedure at home while on a waiting list for more intensive treatment. Future research should also explore if this procedure may reduce problematic behavior that may occur once escape extinction procedures are implemented. At the beginning of the study Sandy engaged in high rates of problem behavior when presented with low-p instructions including the terminal response. However, after exposure to treatment with the demand fading sequence, it was observed anecdotally that general compliance began to increase and overall problem behavior decreased (e.g., complying with instructions to sit down and remain seated for the duration of the session). Additionally, it was also observed that later in the study when problem behavior did occur, the intensity of problem behavior was much less than at the beginning of the study. Specifically, at the beginning of the study Sandy engaged in screaming, crying, elopement, and head banging when prompted to touch the nonpreferred food to her lips. At the end of the study, Sandy independently touched the food to her lips in the absence problem behavior. This is an important observation because it suggests that even though the demand fading procedure was not successful in increasing consumption, it was successful in increasing general compliance as well as compliance with behaviors closer to the terminal response. Thus, this may be a helpful procedure for parents or clinicians to implement with a child prior to beginning more intensive feeding treatments that may include escape extinction procedures. First establishing general 37 compliance and compliance with behaviors closer to the terminal response may ultimately help to reduce the potential of problem behavior increasing in frequency, intensity, and duration (characteristic of an extinction burst) when more intensive feeding treatments such as escape extinction are implemented. The present study demonstrated experimental control and replication of results across participants; however, there are some limitations that should be taken into consideration. First, the present study was not successful in establishing consumption of the target non-preferred food in the treatment II procedure. Although treatment II was successful in increasing behavior closer to the terminal response, the terminal response of consumption was not reached. Second, the reinforcement and prompting procedures for treatments I and II had to be modified for Sandy in order to establish compliance with high-p and low-p instructions, thus deviating from the reinforcement and prompting procedures used for Evan. Also, the additional reinforcement for high-p and low-p instructions make it difficult to determine if it was the additional reinforcement or the high-p instructional sequence that was responsible for behavior change in treatment II. Third, due to the discontinuation of participation it was not possible to complete checks for maintenance of the behaviors achieved in treatment or the generalization of these behaviors to other caregivers. Future research should also further evaluate the maintenance and generalization of behavior established using the high-p instructional sequence combined with demand fading achieved by Penrod and colleagues in 2012. 38 In addition to the above limitations, it should also be noted that participant characteristics were not well controlled for which may account for why results of the current study differed from those reported in previous studies. Specifically, Evan had a fairly short history of food selectivity (approximately one and a half years) whereas Sandy’s history of food selectivity was much longer (approximately 7 years). One would expect better treatment outcomes for Evan given his relatively short history; however, based on information provided in the behavior and compliance parent interview, Evan likely had an additional history of general non-compliance at home with parents which may have contributed to failure to establish consumption of the non-preferred food during treatment. Similarly, information provided in the behavior and compliance parent interview indicated that Sandy had a fairly loose structure and low expectations at home. Participant characteristics may play a significant role in determining the success of antecedent based interventions such as high-p sequences and demand fading. The participants in this study had the same general profile as those described by Penrod et al. (2012), however characteristics of participants in the current study significantly differed from the participant in the Patel et al. (2007) study. The participant in the study conducted by Patel and colleagues was reported to use 2-3 word phrases, followed complex commands, and demonstrated passive food refusal behavior which was described as non-compliance in the absence of problem behavior. In contrast, participants in the current study only followed simple one-step instructions and imitation actions. Evan spoke using 1-3 word phrases; however, Sandy demonstrated a limited vocabulary 39 in that she inconsistently used only single words to communicate wants/needs and primarily engaged in echolalic vocalizations. Additionally, the child’s history of food refusal behavior (i.e., duration of time) should also be considered, as previously mentioned. Specifically, an older child that has a longer history of food selectivity may respond slower to this type of procedure, as was the case with Sandy who was 7.11 years at the start of the study. Another potential predictive characteristic is the structure of the family household as a whole (e.g., rules present in the home, consequences for following or not following those rules, and overall daily routines and structure). Both Evan and Sandy’s parents indicated in the behavior and compliance questionnaire that there were limited household rules and the consequences for following or breaking the rules in existence were fairly unclear. Given the information provided by both Evan and Sandy’s parents in the behavior and compliance parent interview, it was expected that general compliance in the compliance assessment would be representative of that. However, both Evan and Sandy performed at 80% or better during the general compliance assessment. It is likely that the instructions included in that assessment did not accurately assess compliance to every day instructions that they were each presented with by parents at home that may have provided a better overall picture of their general compliance with parents. Future research should reevaluate the instructions used in the general compliance assessment to identify instructions that may provide researchers and clinicians with a better representation of the child’s general level of compliance to instructions given by parents or caregivers. This information may help predict how well a child will respond to 40 intervention. Specifically, if a child complies with less than 60% of general instructions issued by parents or caregivers, this is an indicator that the child’s noncompliance is not isolated and expands to other areas outside of mealtime. Knowing this information would assist researchers and clinicians in identifying the best course of treatment; if a child displays strong compliance to instructions from parents, then they could move forward with treatments specifically targeting food selectivity. However, if the child displays weak compliance to instructions from parents, then the researcher or clinician might intervene more effectively by first implementing treatment that targets increasing compliance in a demand context outside of food consumption. For a child that displays general non-compliance across demand types, it may be best to start with instructions that can be prompted in order to establish general compliance and instruction following and this is not possible with food consumption, as eating is one of the few behaviors that a child has complete control over. Thus, having more information about the child’s overall level of compliance will better guide researchers and clinicians in decision-making regarding the type of treatment that may be most beneficial for the child at that time. Future research should continue to evaluate the strength of the high-p sequence with and without demand fading as well as participant characteristics that may help to predict the effectiveness of this treatment compared to other treatment options such as EE. 41 APPENDIX A Pre-treatment Parent Interview: Feeding Pre-Treatment Parent Interview Date: Child’s name: Child’s age: Child’s weight: Child’s height: Family status (married/single/divorced): 1. Interviewer(s): Parents/guardian: Phone number: Email: Child’s diagnosis: Siblings: Feeding What foods does your child currently eat from each food group? Fruits: _________________________________________________________ Vegetables: _____________________________________________________ Dairy products: __________________________________________________ Meats: _________________________________________________________ Breads/cereals: __________________________________________________ Sweets/snacks:__________________________________________________ 2. Are there foods that your child previously ate, but does not eat now? Why? 3. Please describe what your child typically eats for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Breakfast: _________________________________________________________ Lunch: ___________________________________________________________ Dinner: ___________________________________________________________ 4. What are feelings regarding what your child currently eats? What would you like to change? 5. What techniques do you use during meal times (offering choice, praise, coaxing, preparing different meal, etc.)? 6. What does meal time presentation look like (who presents/prepares the meal, does child feed self, location, seating, others present during meal time)? 7. Describe your child’s behavior during meal times 8. What are your child’s most preferred and least preferred foods? What foods would you like your child to start eating? 9. Please rate the following questions on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 meaning extremely dissatisfied, 2 meaning dissatisfied, 3 meaning minimally satisfied, 4 meaning quite satisfied with some room for improvement, and 5 meaning extremely satisfied. Question: Please Circle One: Are you satisfied with the foods your child currently eats? 1 2 3 4 5 Are you satisfied with the quantity of food your child eats? 1 2 3 4 5 Are you satisfied with how your child behaves during meals? 1 2 3 4 5 Are you satisfied with your child’s self-feeding skills? 1 2 3 4 5 Are you satisfied with your child’s current weight? 1 2 3 4 5 42 APPENDIX B Pre-treatment Parent Interview: Behavior and Compliance Date: Child’s name: Child’s age: Child’s weight: Child’s height: Family status (married/single/divorced): Pre-Treatment Parent Interview Interviewer(s): Parents/guardian: Phone number: Email: Child’s diagnosis: Siblings: 1. General Information Is your child currently taking any medications? 2. Describe your child’s treatment history 3. What is your child’s primary form of communication? 4. Does your child imitate others? 5. Does your child respond to social contingencies (praise, pleasing others)? 6. Does your child show interest in interacting with peers? 7. Tell us about your family (what do you like to do together, day time/night time routines, what does a typical week day/weekend look like). What changes would you like to see, if any, in your family life (things you would like to do as a family that you aren’t doing now, changes you would like to see in your daily routines)? What do you think the biggest barrier is to these things happening? 8. 9. 1. General Compliance What are some of the “house rules” that all members in the family are expected to follow? That the children are expected to follow? 2. Does your child follow these rules? How do you respond if your child does not follow a given rule? How do you respond if your child does follow a rule? 3. What are your expectations for your child (does he/she have a bed time, chores, mealtime schedule, homework, etc.)? 4. How does your child respond when you give him/her instructions? What instructions does he/she follow willingly? What are chEvanging instructions for him/her to follow? How do you let him/her know when he/she is doing a good job? How do you let him/her know when he/she is not doing what you want him/her to do? 5. How does your child respond to changes in routine? How do you prepare for changes in your child’s routine? Does your child engage in any other rigid behavior? 6. Does your child engage in any compulsive or repetitive behavior? How do you respond? 7. Are there any tasks/activities that your child used to do that they don’t do now? 8. Does your child engage in any non-compliance? What does this look like? What are the common antecedents to noncompliance? How do you respond? 9. How do you respond if your child wants something a different way than the way you are doing it? 10. What are some situations that make your child uncomfortable/anxious/upset? What does he/she typically do in these situations? How do you respond to his/her behavior? What are some ways that you have tried to help him/her “cope” in these situations? How have these strategies worked for you? For your child? 43 APPENDIX C Food Related Compliance Assessment Data Sheet Date: _______________ Researcher: _____________________________ Primary / IOA Participant:______________________________ Foods: 1.________________ 2.________________ 3.________________ Instructions Present all demand fading steps for each food item , run this 1x for each food. Trial presentation is as follows: present the empty spoon or single bite of food and the vocal instruction paired with a model of the target response for 5 seconds. If the participant does not engage in the target response then repeat the instruction and model for 5 additional seconds. Any refusal or inappropriate mealtime behavior should be ignored. If the participant engages in the target response, score as (+) and deliver brief verbal praise. If the participant does not comply, score as (-) and remove the food. Regardless of the response, present the next trial immediately following the end of a given trial. Food: 1. “Take a bite” (empty spoon) 2. “Touch the (food)” 3. “Hold the (food)” 4. “Smell the (food)” 5. “Kiss the (food)” 6. “Lick the (food)” 7. “Put the (food) on your tongue” (holds it for 3 seconds) 8. “Put the (food) in your mouth” 9. “Chew the (food)” (chews it at least 5 time) 10. “Take a bite” (bite of food) 1 2 3 44 APPENDIX D General Compliance Assessment Data Sheet Please present the below instructions/imitation tasks to your child in a way that you would naturally. Researchers will indicate a + if the child complies with the given instruction and a minus if the child does not comply with the given instruction. Instructions stand up come here sit down give me (item) clean up Imitation rolling toy car clapping hands waving standing up putting toy away 45 APPENDIX E Baseline Data Sheet Condition: Baseline Bite Date: _______ Prompt Session #: _______ Trial Pres. Initials: _______ SR+ PB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Comments: Condition: Baseline Bite 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Comments: Prompt Date: _______ Session #: _______ Trial Pres. Initials: _______ SR+ PB 46 APPENDIX F Treatment Data Sheet Condition: Treatment HP Prompt Date: _______ HP Prompt LP Prompt Session #: _______ Trial Pres. Initials: _______ SR+ PB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Comments: Condition: Treatment HP 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Comments: Prompt Date: _______ HP Prompt LP Prompt Session #: _______ Trial Pres. Initials: _______ SR+ PB 47 REFERENCES Ahearn, W., Castine, T., Nault, K., & Green, G. (2001). An assessment of food acceptance in children with autism or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 505511. Ahearn, W. H., Kerwin, M. E., Eicher, P. S., Lukens, C. T. (2001). An ABAC comparison of two intensive interventions for food refusal. Behavior Modification, 25, 385-405. Bachmeyer, M. H. (2009). Treatment of selective and inadequate food intake in children: a review and practical guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 2, 43-50. Bachmeyer, M. H., Piazza, Fredrick, L. D., Reed, G. K., Rivas, K. D., & Kadey, H. J. (2009). Functional analysis and treatment of multiply controlled inappropriate mealtime behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42, 641-658. Bandini, L. G., Anderson, S. E., Curtin, C. Cermak, S. Evans, E. W., Scampini, R., Maslin, M., & Must, A. (2010). Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 157, 259264. Belfiore, P. J., Basile, S. P., & Lee, D. L. (2008). Using a high probability command sequence to increase classroom compliance: the role of behavioral momentum. Journal of behavioral Education, 17, 160-171. 48 Belfiore, P. J., Scheeler, M. C., & Klein, D. (2002). Implications of behavioral momentum and academic achievement for students with behavior disorders: theory, application, and practice. Psychology in Schools, 39, 171-179. Belfiore, P. J., Lee, D. L., Vargas, A. U., & Skinner, C. H. (1997). Effects of highpreference single-digit mathematics problem completion on multiple-digit mathematics problem performance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 327-330. Brandon, P. K. & Houlihan, D. (1997). Applying behavioral theory to practice: an examination of the behavioral metaphor. Behavior Interventions, 12, 113-131. Dawson, J. E., Piazza, C. C., Sevin, B. M., Gulotta, C. S., Lerman, D., & Kelley, M. L. (2003). Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 105-108. Fisher, W. Piazza, C. C., Bowman, L. G., Hagopian, L. P., Owens, J. C., & Slevin, I. (1992). A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 491-498. Kern, L. & Marder, T. J. (1996). A comparison of simultaneous and delayed reinforcement as treatments for food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 29, 243-246. 49 Knox, M., Rue, H. C., Wildenger, L., Lamb, K., & Luiselli, J. K. (2012). Intervention for food selectivity in a specialized school setting: teacher implemented prompting, reinforcement, and demand fading for an adolescent student with autism. Education and Treatment of Children, 35, 407-417. Lee, D. L., Belfiore, P. L., Scheeler, M. C., Hua, Y., & Smith, R. (2004). Behavioral momentum in academics: using embedded high-p sequences to increase academic productivity. Psychology in the Schools, 41, 789-801. Lee, D. L., & Laspe, A. K. (2003). Using high-probability request sequences to increase journal writing. Journal of Behavioral Education, 12, 261-273. Lee, D. L., Scheeler, M. C., & Klein, D. (2002). Implications of behavioral momentum and academic achievement for students with behavior disorders: theory, application, and practice. Psychology in Schools, 39, 171-179 Levin, L. & Carr, E. G. (2001). Food selectivity and problem behavior in children with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification, 25, 443-470. Luiselli, J. K. (2000). Cueing, demand fading, and positive reinforcement to establish self-feeding and oral consumption in a child with chronic food refusal. Behavior Modification, 24, 348-358. Luiselli, J. K., Ricciardi, J. N., & Gilligan, K. (2005). Liquid fading to establish milk consumption by a child with autism. Behavioral Interventions, 209, 155-163. 50 Mace, F. C., Hock, M. L., Lalli, J. S., West, B. J., Belfiore, P., Pinter, E., & Brown, D. K. (1988). Behavioral momentum in the treatment of noncompliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 21, 123-141. Najdowski, A. C., Wallace, M. D., Doney, J. K., & Ghezzi, P. M. (2003). Parental assessment and treatment of food selectivity in natural settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 383-386. Najdowski, A. C., Wallace, M. D., Reagon, K., Penrod, B., Higbee, T. S., & Tarbox, J. (2010). Utilizing a home-based parent training approach in the treatment of food selectivity. Behavioral Interventions, 25, 89-107. Nevin, J. A., Mandell, C., & Atak, J. R. (1983). The analysis of behavioral momentum. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 39, 49-59. Pace, G. M., Ivancic, M. T., Edwards, G. L., Iwata, B. A., & Page, T. J. (1985). Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 249-255. Patel, M. Reed, G. K., Piazza, C. C., Mueller, M., Bachmeyer, M. H., & Layer, S. A. (2007). Use of a high-probability instructional sequence to increase compliance to feeding demands in the absence of escape extinction. Behavioral Interventions, 22, 305-310. Penrod, B., Gardella, L., & Fernand, J. (2012). An evaluation of a progress highprobability sequence combined with low-probability demand fading in the treatment of food selectivity. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45, 527-537. 51 Penrod, B., Wallace, M. D., Reagon, K., Betz, A., & Higbee, T. S. (2010). A component analysis of a parent-conducted multi-component treatment for food selectivity. Behavioral Interventions, 25, 207-228. Plaud, J. J. & Gaither, G. A. (1996). Human behavioral momentum: implications for applied behavior analysis and therapy. Journal of Behavioral Therapy & Experimental Psychology, 27, 139-148. Schreck, K. A., Williams, K. & Smith, A. F. (2004). A comparison of eating behaviors between child with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 433-438.