MULTICULTURAL INFUSION OF GRADUATE LEVEL COUNSELING COURSES Claire McLean

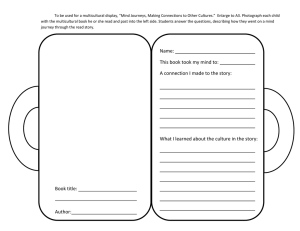

advertisement