Document 16081207

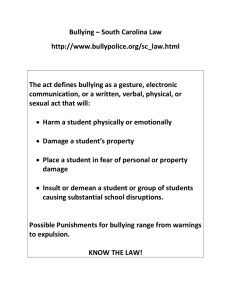

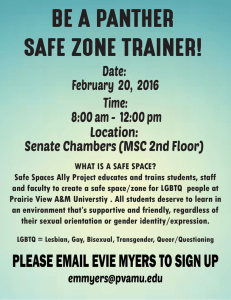

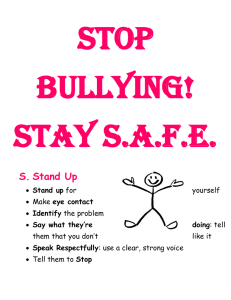

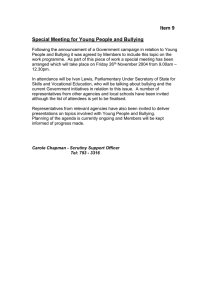

advertisement