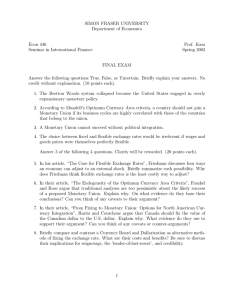

Chapter 2 International Monetary System Management 3460 Fall 2003

advertisement

Management 3460 Institutions and Practices in International Finance Fall 2003 Greg Flanagan Chapter 2 International Monetary System Chapter Objectives: This chapter serves to introduce the student to the institutional framework within which: international payments are made; movement of capital is accommodated; exchange rates are determined. 2 September 16-22, 2003 Outline Money The evolution of the International Monetary System Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Euro and the European Monetary Union Currency Crisis Mexican Peso Crisis Asian Currency Crisis Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes 3 September 16-22, 2003 Money Means of exchange Unit of account Store of value Commodity money Fiat money Characteristics of good money: 4 September 16-22, 2003 Bimetallism: Before 1875 A “double standard” in the sense that both gold and silver were used as money. Some countries were on the gold standard, some on the silver standard, some on both. Both gold and silver were used as international means of payment and the exchange rates among currencies were determined by either their gold or silver contents. Gresham’s Law: ‘bad money drives out good money’ implied that it would be the least valuable metal that would tend to circulate. Not ‘systematic’-- many disruptions in trade. 5 September 16-22, 2003 Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 Gold standard est. 1821 Bank of England pound notes redeemable for gold. Full gold standard 100% partial: more notes than gold. 6 September 16-22, 2003 Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 Conditions Gold alone was assured of unrestricted coinage; There was two-way convertibility between gold and national currencies at a stable ratio. Gold could be freely exported or imported. The exchange rate between two country’s currencies would be determined by their relative gold contents. 7 September 16-22, 2003 Classical Gold Standard: 1875-1914 Highly stable exchange rates under the classical gold standard provided an environment that was conducive to international trade and investment. Misalignment of exchange rates and international imbalances of payment were automatically corrected by the price-specieflow mechanism. 8 September 16-22, 2003 Price-specie-flow mechanism. Arbitrage will keep the exchange rates equal. Trade flows will adjust to exchange rates by the flow of gold. Money Supply X Velocity =Prices X Quantities. MsV=PQ M = f (Gold) If V and Q constant a G ha Ms h a Ph a eXportsi iMportsh a Gi until X=M (trade balance) 9 September 16-22, 2003 Price-specie-flow mechanism. Problems: Limited supply of new gold restricts the growth of world trade and investment due to insufficient medium of exchange. National economies respond to the exchange rate (gold reserves) rather than real production possibilities. any national government could abandon the standard. 10 September 16-22, 2003 Interwar Period: 1915-1944. Gold flow ceased due to WW1 Exchange rates fluctuated as countries widely used “predatory” depreciations of their currencies as a means of gaining advantage in the world export market. Attempts were made in the 1920s to restore the gold standard, however, major countries (i.e.USA, GB) ‘sterilized’ gold in order to pursue domestic interests. Hyperinflation in Germany, the stock market crash, and the great depression result gold standard abandoned. international trade and investment was profoundly diminished. 11 September 16-22, 2003 Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 Named for a 1944 meeting of 44 nations at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The purpose was to design a postwar international monetary system. The goal was exchange rate stability without the gold standard. The result was the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. 12 September 16-22, 2003 Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 US$ based Gold exchange Standard: the U.S. dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce and other currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar. Each country was responsible for maintaining its exchange rate within ±1% of the adopted par value by buying or selling foreign reserves as necessary. 13 September 16-22, 2003 Bretton Woods System: 1945-1972 Increasing U.S. trade deficits occurred in the late 1950s and 1960s. Triffin Paradox: h need for reserves a M > X a $ outflow a more $ than gold at $35 per ounce. France wants Gold for $ a pressure on reserves a Interest Equalization Tax (1963) and the Foreign Credit Restraint Program (1965-68) Special Drawing Rights (SDR) established by IMF Smithsonian agreement: US$38/ounce; band h 2.25% 1973 US$42/ounce 1973 the US$ is released from the gold standard. 14 September 16-22, 2003 Special Drawing Rights Weighted average of currencies Currency 1981-85 1986-90 1991-95 19962000 20012005 US$ 42 42 40 39 45 Euro 29 German Mark 19 19 21 21 Japanese Yen 13 15 17 18 15 British pound 13 12 11 11 11 French Franc 13 12 11 11 15 September 16-22, 2003 Supply and Demand Review A digression 16 September 16-22, 2003 The Market Model Demand and Supply Shows how the price and output of a commodity are determined in a competitive market. When relevant variables change it shows how these changes affect the price and output. 17 September 16-22, 2003 Demand (coffee) Price. We expect that as the price goes up, the quantity demanded goes down and vice versa. Income. Changes in income modify people’s consumption opportunities. It is hard to say a priori, however, what effect such changes have on consumption of a given good. normal good: as incomes go up, people use some of their additional income to purchase more coffee. 18 September 16-22, 2003 Demand inferior good: it may be that as incomes increase, people consume less coffee, perhaps spending their money on cognac instead. We expect that changes in income affect demand one way or the other, but in some cases it is hard to predict the direction of the change. Px Inferior good: I h a Dh & v. v. Normal good: I h a Di & v. v. 19 September 16-22, 2003 Demand Prices of related goods. substitutes: if the price of tea goes up people can substitute coffee for tea, this increase in the price of tea increases the amount of coffee people wish to consume. complements: if the price of cream goes up and if people consume coffee and cream together, this tends to decrease the amount of coffee consumed. Tastes. The extent to which people “like” a good affects the amount they demand. Expectations 20 September 16-22, 2003 Demand A demand schedule (or demand curve) is the relation between the market price of a good and the quantity demanded of that good during a given time period, other things being the same. (Economists often use the Latin for “other things being the same,” ceteris paribus.) Dx = F(Px, I, Psub, Pcomp, T, Ex, etc.) Dx =f(Px)c.p. A hypothetical demand schedule for coffee is represented graphically by curve Dc=f(Pc) 21 September 16-22, 2003 Demand Curve Change in ‘Quantity Demanded’ due to a change in Price 22 September 16-22, 2003 Increase in Demand due some variable other than Price 23 September 16-22, 2003 Supply Price. We expect that as the price goes up, the quantity supplied goes up and vice versa. It is reasonable to assume that the higher the price per pound of coffee, the greater the quantity profit-maximizing firms are willing to supply. Costs, or Prices of inputs. Coffee producers employ inputs to produce coffee—labour, land, and fertilizer. If their input costs go up, the amount of coffee that they can profitably supply at any given price goes down. 24 September 16-22, 2003 Supply Conditions of production. The most important factor here is the state of technology. If there is a technological improvement in coffee production, the supply increases. Other variables. also affect production conditions. For agricultural goods, weather is important. Several years ago, for example, flooding in Latin America seriously reduced the coffee crop. 25 September 16-22, 2003 Supply A supply schedule (or supply curve) is the relation between the market price of a good and the quantity demanded of that good during a given time period, other things being the same. (Economists often use the Latin for “other things being the same,” ceteris paribus.) Sx = F(Px, Costs, Tech, etc.) Sx =f(Px)c.p. A hypothetical supply schedule for coffee is represented graphically by curve Sc=f(Pc) 26 September 16-22, 2003 Supply Curve 27 September 16-22, 2003 Decrease in Supply due some variable other than Price 28 September 16-22, 2003 Equilibrium The demand and supply curves provide answers to a set of hypothetical questions: If the price of coffee is $2 per pound, how much are consumers willing to purchase? If the price is $1.75 per pound, how much are firms willing to supply? Neither schedule by itself tells us the actual price and quantity. But taken together, the schedules determine price and quantity. 29 September 16-22, 2003 Equilibrium equilibrium—a situation that tends to be maintained unless there is an underlying change in the system. Quantity demanded equals quantity supplied. In the next Figure the demand schedule Dc is superimposed on the supply schedule Sc. 30 September 16-22, 2003 Market Equilibrium 31 September 16-22, 2003 i.e. suppose the price is P1 dollars per pound. At this price, the quantity demanded is Q1 and the quantity supplied is Q1 Price P1 cannot be maintained, because firms want to supply more coffee than consumers are willing to purchase. This excess supply tends to push the price down, as suggested by the arrows. 32 September 16-22, 2003 Decrease in Supply due to some variable other than price changing. i.e. Costs of production increase. 33 September 16-22, 2003 Arbitrage Market A Market B P P S S S* Pe PB D D* D QY Sell in the high market a Sh QY Buy in the low market a Dh Arbitrage brings markets together over space, bringing a common price (except transaction costs). 34 September 16-22, 2003 Back to the Main History 35 September 16-22, 2003 The Flexible Exchange Rate System 1973— The Jamaica Agreement 1976 Flexible exchange rates were declared acceptable to the IMF members. Central banks were allowed to intervene in the exchange rate markets to iron out unwarranted volatilities. Gold was abandoned as an international reserve asset. 36 September 16-22, 2003 The Flexible Exchange Rate System 1973— The IMF continued assistance to countries experiencing Balance of Payments and foreign exchange problems. And non-oil-exporting countries and lessdeveloped countries were given greater access to IMF funds. However, assistance was conditional on practicing IMF proscribed economic policy a resentment and dissent. 37 September 16-22, 2003 1973—The Flexible Exchange Rates: The Plaza Accord 1985 G5 Agreed to let the $US slide The Louvre Accord 1987 G7 cooperate for greater exchange rate stability More closely coordinate economic policies 38 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Independent Float Market determined Some management (intervention) to moderate the rate of fluctuations. The largest about 41 countries, (including Canada). 39 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Managed Float Active government intervention in market forces to set exchange rates. With no preannounced path for the exchange rate About 42 countries 40 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Exchange rates with crawling bands Central rate with +/- margins Adjusted periodically on set dates or due to set quantitative indicators. ~6 countries i.e. Venezuela 41 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Crawling Pegs Adjusted periodically on set dates or due to set quantitative indicators. ~4 countries i.e. Bolivia 42 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Pegged with horizontal bands Formal or de facto fixed rate with margins greater than +/- 1% 5 countries i.e. Denmark 43 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Conventional Pegged rate pegged to a major currency ($) or basket of currencies (SDR) Narrow band fluctuation <1% ~40 countries i.e. China 44 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements Currency Board arrangements Legislated commitment to exchange domestic currency for a specified currency at a fixed exchange rate Combined with restrictions on the issuing authority 9bioard) to ensure its legal obligations. i.e. Hong Kong a US$; Estonia a € 45 September 16-22, 2003 Current Exchange Rate Arrangements No separate Currency (legal tender) Another country’s currency circulate or the country belongs to a currency union i.e. Ecuador a US$ 46 September 16-22, 2003 European Monetary System The euro € is the single currency of the European Monetary Union which was adopted by 12 Member States on 11 on January 1st 1999. and Greece in 2000. Marks, Francs, Lira, etc. are no longer independent currencies. Fixed exchange rates: European Central Bank 47 September 16-22, 2003 1 Euro is Equal to: 40.3399 BEF Belgian franc 1.95583 DEM German mark 166.386 ESP Spanish peseta 6.55957 FRF French franc .787564 IEP Irish punt 1936.27 ITL Italian lira 40.3399 LUF Luxembourg franc 2.20371 NLG Dutch gilder 13.7603 ATS Austrian schilling 200.482 PTE Portuguese escudo 5.94573 FIM Finnish markka 40.750 GRD 48 Greek Drachma September 16-22, 2003 European Monetary System Benefits Reduced transaction costs elimination of exchange rate uncertainty No hedging costs Promote cross border investments and trade Increased competition a prices i Integration of financial markets Continental capital markets Political cooperation and peace 49 September 16-22, 2003 European Monetary System Costs Loss of sovereignty over national monetary and exchange rate policies. Mundell: Theory of optimal common currency area. currency common a factor resource mobility: differing economic conditions mean resources move. Immobility of resources a different currencies adjust to differing economic conditions. 50 September 16-22, 2003 The ‘Trilemma’ 1. Fixed Exchange rate. 2. Free international flows of capital 3. An independent monetary policy a Can choose only two 51 September 16-22, 2003 The ‘Trilemma’ Fixed rates reduce uncertainty a h foreign trade tie monetary and fiscal policies to exchange rate maintenance 52 September 16-22, 2003 The ‘Trilemma’ Flexible exchange rates increase uncertainty. • however, hedging can be used monetary and fiscal policies can be independent and used to achieve other goals. No safeguards to prevent currency crises. 53 September 16-22, 2003 Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Suppose the exchange rate is US$1.40/£ today. In the next slide, we see that the quantity demanded for British pounds far exceed the quantity supplied at this exchange rate. The U.S. experiences trade deficits. 54 September 16-22, 2003 Dollar price per £ (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Supply (S) Demand (D) $1.40 Trade deficit 55 QS QD Q of £ September 16-22, 2003 Dollar price per £ (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Supply (S) $1.60 Demand (D) Dollar depreciates (flexible regime) $1.40 Demand (D*) 56 Q D = QS Q of £ September 16-22, 2003 Under a flexible exchange rate regime, the dollar will simply depreciate to $1.60/£, the price at which supply equals demand and the trade deficit disappears. 57 September 16-22, 2003 Under a flexible exchange rate regime, the dollar will simply depreciate to $1.60/£, the price at which supply equals demand and the trade deficit disappears. 58 September 16-22, 2003 Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes If the exchange rate is “fixed” at US$1.40/£, and thus the imbalance between supply and demand cannot be eliminated by a price change. The US government would have to intervene in order to demand or supply i.e. a shift of demand from D to D* through contractionary monetary and fiscal policies. 59 September 16-22, 2003 Dollar price per £ (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Supply (S) Contractionary policies (T h) Demand (D) (fixed regime) $1.40 Demand (D*) 60 QD* = QS Q of £ September 16-22, 2003 Dollar price per £ (exchange rate) Fixed versus Flexible Exchange Rate Regimes Supply (S) Supply Contractionary (S*) policies i h (fixed regime) $1.40 61 Demand (D) Q of £ QD = QS*September 16-22, 2003