ONLINE TUTOR CONFERENCING: Nancy Wilson

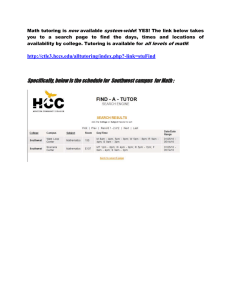

advertisement