1 Baptism Mark pulled the brown bedspread over the smooth, tan sheets,...

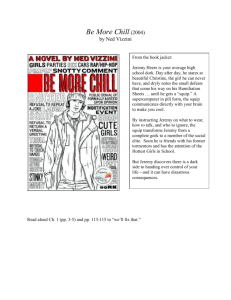

advertisement