ROCKHURST UNIVE RSITY LEADER D EVELOPM ENT WHITE PA PER

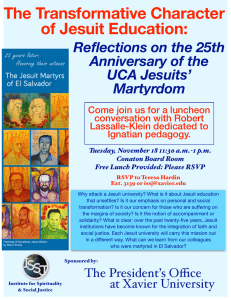

advertisement

ROCKHURST UNIVERSITY LEADER DEVELOPMENT WHITE PAPER We want graduates who will be leaders concerned about society and the world in which they live…In short, we want our graduates to be leaders-inservice. That has been the goal of Jesuit education since the sixteenth century. It remains so today. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J Superior General Emeritus of the Society of Jesus June 1989 address at Georgetown University Rockhurst University’s motto, “Learning, Leadership, and Service in the Jesuit tradition,” reflects three goals that are interconnected. Together these three goals embody the spirit of Ignatius and the Society of Jesus—the Jesuits. Jesuit tradition suggests that becoming citizens who serve others requires the lifelong pursuit of learning as well as development of our ability to lead. Members of the Rockhurst community prepare for this journey by becoming part of the university’s culture, where the daily cycles revolve around the pursuit of knowledge, self-awareness, and moral character, and whose traditions are continually being made richer as they are passed on to each new generation of students, faculty, and staff. Rockhurst aspires to build upon its century of history to become even more deliberate in assisting students to develop their God-given capability to lead others. Leading is a human endeavor, and it is not a role reserved for select individuals or those holding titles we often associate with being a leader. Leaders are those who choose—who make conscious decisions to intervene in the mundane routine of daily life—to make their situation, and the situation of others, better. Leaders are those who ask, “How might we improve this situation?” or, “Could we consider doing this another way?” Leaders act out of the recognition of need and the conviction that they can make a difference within their sphere of influence regardless of the titles or position. 1 Leader formation has been a goal of a Rockhurst education since 1910. That tradition, combined with a shared Catholic Jesuit identity reaching back over 450 years, informed our strategic planning process beginning in 2006. That process led to the development of revised mission, vision and values statements as well as “18 Pathways to the Vision” that will guide the university in the coming years. From the statement and directives found in “Pathways,” leader development emerged as a core and central theme of the university’s future, and it is the unifying force of Rockhurst’s educational mission. Part of our vision includes the phrase, to “be nationally recognized for transforming lives and forming leaders.” 1 This is accomplished through integrative learning experiences designed to prepare the student for life-long transformational service. 2 This white paper takes a step forward by providing common language around what leadership is and using selected characteristics to describe the basis for its uniqueness. The definition that is presented reflects the traditions and values of Jesuit tradition and provides the basis for our understanding of how we develop leaders at Rockhurst. The “journey of becoming” applies across our community. We are all engaged in this journey and share the goals of developing both as persons and in our ability to lead others. Students enter our community at an earlier stage of development, and their growth at Rockhurst prepares them for their future. This growth relies on the influence of staff and faculty who are themselves in a process of growth and continuous development as leaders and life-long learners. As faculty and staff reflect upon their own experiences, they have the opportunity to intentionally model the tenets of our tradition in daily interaction with others across campus. The ultimate goal is that all members of the community emerge as confident and reflective “men and women for others” through this collaborative effort.3 This paper has a fourfold structure. First, it seeks to describe the role of Jesuit tradition in our understanding of leadership. Second, the paper presents a definition of leadership and discusses the values and characteristics that have informed our definition. Third, a set of leader development outcomes are presented to orient program development across our university community. Finally, the paper summarizes a model of learning that serves to anchor achievement of these objectives. We hope that this paper will inspire faculty and staff to find their own ways to promote Rockhurst’s leader development objectives and our shared vision. In addition, we hope that this paper will invite deeper discussion on how we can broaden our 2 students’ preparation to have impact in their spheres of influence upon graduation and throughout their lives. A. The Role of Jesuit Tradition in Leader Development The Jesuit tradition has always sought to form persons who understand their place and role in the world. By understanding their role and purpose, these persons may use their knowledge and abilities to act courageously, wisely, and reflectively to serve God, to add to the glory of God’s creation, and to serve other human beings. The Jesuit tradition seeks to assist individuals in their personal growth and in their ability to be leaders in changing our world for the better. Leadership in the Jesuit educational tradition is interwoven with both learning and service. While many educational traditions and institutions emphasize one of the individual elements (generally learning), what is distinctive about the Jesuit tradition is that it understands learning, leadership, and service as being interrelated and mutually supportive. Profound personal growth occurs by integrating the cultivation of the mind (learning), the development of ourselves and our skills to initiate change (leadership), and the recognition of our responsibilities to others (service). 4 Though none of these three elements can be fully understood in isolation we must briefly discuss learning and service in their relation to leadership and leader development. Learning in the Jesuit tradition is directed toward knowledge of God's will revealed in creation and discovered through many intellectual pursuits and academic disciplines, inside and outside of the classroom. Learning is found in the rhythms of daily work and life and is a path for attaining a greater understanding and reverence for the majesty of the world we live in. Growing reverence in turn leads to a genuine care for the world and for the people with whom we share it. Thus, learning is intimately tied to the Jesuit mission of serving others for the purpose of improving their physical, intellectual, spiritual, and moral well-being. Greater learning allows us to care for the whole person and to more effectively serve with compassion in whatever way our efforts are needed. Leaders in learning actively search to discover truth and moral values, for learning exposes ignorance, falsehood, prejudice, and injustice. The Jesuit tradition also recognizes that effective leaders lead with the motivation to serve others; we not only serve the well-being of others but also strive to change the conditions that afflict others. The Jesuit tradition places special emphasis on promoting 3 the cause of justice for all persons in all sectors of society; therefore, the key focus of learning in the Jesuit tradition is recognizing and developing one’s own capacity to serve others to alleviate the causes of injustice. Leaders in service motivate themselves and others to direct their efforts toward the assistance of others. They seek to alleviate poverty, ignorance, and suffering through direct acts of assistance, but they also create transformational opportunities for others, especially through education and leadership training. Leaders in service thereby create more leaders dedicated toward serving, which captures Fr. Kolvenbach’s idea of “multiplying agents.”5 Ultimately, leaders work for the transformation of individuals so that each is liberated to realize his or her best potential. Leaders also work toward transforming institutions to rectify injustices. They direct their abilities and their energy into adding to the goodness of creation. Leading in the Jesuit tradition may be better understood not as a particular way of accomplishing goals but as a way of being and a way of living. B. Defining Leadership Rockhurst students begin developing their leadership capabilities by learning what leadership in the Jesuit tradition means. The definition below describes what leadership is. However, to understand what distinguishes leadership in our Jesuit tradition, we must also examine the how and why of leadership. These are discussed following the definition of leadership. Leading combines innate qualities with learned skills that emerge and develop in every human being over time—to the extent that growth is pursued. A person’s capacity to lead others at a given moment reflects the individual’s own stages of selfawareness, personal development, as well as learned skills and intentions. Leader development therefore involves an ongoing process of personal growth as well as learning leadership skills. For our purposes, leadership in the Jesuit tradition may be defined as the following: Leadership is an overflow of spirit that inspires and influences others to join together to achieve worthy purposes. Leading as understood within the Jesuit tradition suggests that each person’s ability to lead is an expression of both the distinct person they are presently and the person they are becoming. Spirit in the sense we use it here means the whole person and all that makes each of us unique: body, mind, personality, and character. The impetus to 4 lead comes ultimately from within one’s own self. An understanding of one’s self, one's place in this world, and one's interrelatedness to others ignites a fire within to embrace this world, with its goodness and its flaws. Our tradition aspires that leaders add to the world's beauty by being transformed into an ever more effective servant of that potential goodness in all persons. Our whole being reveals our vision, passion, and intention, and it reflects the dynamic expression of this fire and a commitment to be a force for beneficial change in the world. Thus, from the Jesuit tradition, leading must be understood as more than simply the adoption of certain behaviors or practices; leading is better understood as a way of being and actively engaging with our world. A leader also inspires others to act for the sake of good. The term’s early uses suggested blowing into, inflame, or animate with an idea of purpose; stimulating; provoking creativity, effort and enthusiasm; or even resuscitating a situation or organization.6 7 These ideas convey visual images of what leaders do as they make intentional choices to challenge the status quo to make their communities better in big and small ways. Through cultivation of this ongoing influence of others, a leader transforms that community in direct and indirect ways. A leader directly works to improve the lives of the members of his or her community in both the small personal interactions of daily life and the larger and more visible ways of attending to the well-being of others. However, leaders also transform communities in indirect ways. Often leaders can inspire others to direct their own creative efforts towards worthy purposes simply by serving as an example of service and engagement. Thus, a leader may indirectly inspire others to find the transformative power needed to realize their best potential. A leader can spark by words and deeds the same inner fire in all with whom he or she comes in contact. The idea of joining together is implied throughout the discussion above. The thread that runs through our tradition suggests that leadership is highly participatory. Whether we inspire others directly or indirectly, leaders seek to find the best response to the problem at hand by eliciting the best knowledge, skills, experience, and personal characteristics of others in the community. Through this process, not only are good solutions found, but all members have the opportunity for personal growth and development. The process honors solving of the problems (ends) as well as the methods we identify to solve them (means). Leadership in the Jesuit tradition flows from a set of values, beliefs, and assumptions about how the world works and is expressed in acts of service and other 5 “worthy purposes.” As we seek to lead in this tradition our leadership is directional— undertaken with the underlying intent of participating in purposes “for the greater glory of God,” (Ad Majorem Dei Gloria). From the mundane work and interactions of daily life to more visible positions and dramatic endeavors such as relieving poverty and social injustice, all of our undertakings reflect the belief that we are participating in efforts greater than ourselves. Sometimes, achieving such purposes require risktaking and courage. Values of Leadership The Jesuit tradition conceptualizes leadership not simply as a set of practices and behaviors but as a way of being or living. There are a group of personal and moral characteristics expressive of core values that we aspire to and seek to more fully reflect as we interact with and seek to influence others. While the characteristics discussed below are not exhaustive, they are distinctively displayed by leaders seeking to embody Jesuit Catholic tradition and are intended to illuminate the definition above. Magis (translated literally as “more”) suggests excellence in all endeavors: The concept of Magis emerges from Jesuit tradition as grandeur, dignity, inspiring awe or reverence, elevation of manner.8 Magis implies that our leading and our service is never finished; there is always more to be done. Magis leadership “does not depend so much on a single extraordinary individual; rather, it depends more on a way of being that is life-affirming and a belief that at the core of all systems (including people) lies a positive center that can be engaged.”9 Perhaps more simply, Magis means constantly searching for ways to improve on “what is” or finding “some better approach to the problem at hand or some worthier challenge to tackle.”10 Finding God in All Things: Our understanding of leadership begins with recognition of the value and worth of every person. Each person is distinct, and all are created in the image of God—Imago Dei. Hence, we see the image of God in those we lead. Flowing from the concept of Imago Dei, leaders in this tradition interact with others in ways demonstrating the value and dignity of every human person. Being able to recognize and respect the uniqueness of every person is part of what we refer to as finding God in all things. This belief serves as the basis for how we go about distinctively influencing (leading) others.11 Every person leads, and each does so as an outflow of who they are 6 presently and who they are in the process of becoming.12 13 Leader formation and personal development is a continuous, life-long process whereby all people seek to incarnate their unique and intended design as agents of grace in nurturing good and confronting anything that causes harm.14 15 The intention of Rockhurst is to form leaders in the Jesuit tradition while realizing that all learning marks progress along a continuous journey. Cura Personalis or “Care for the Whole Person”: Leaders formed in the Jesuit tradition have profound respect for the unique dignity and capacity of others. Out of this respect for others, leaders seek to help them to reach their fullest potential.16 We should understand cura personalis as grounded in a kind of practical love, which is less of an emotional state and more of a disposition to act. Here love means first facing the world with a confident, healthy sense of self as endowed with talent, dignity, and the potential to bring about change. This self-awareness then allows an individual to recognize and commit passionately to honoring and unlocking that potential in others. Love seeks to meet the needs of the organization while continuing to respect the dignity of the individual. Love allows one to create environments bound and energized by loyalty, affection, and mutual support. Love is best seen as a practical component of leadership rather than simply a motivator.17 Reflection and Discernment: Reflection and discernment have uniquely prominent roles in the life of a leader formed in the Jesuit tradition. Reflective practices rooted in Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises create a deep self-awareness of one’s own emotions, values, and experiences as well as sensitivity toward the perspectives of others. The process of becoming more self-aware also includes developing a sense of personal priorities, mission, and purpose. Leaders need to be knowledgeable about their field to make informed choices, but they also need to seek an honest and accurate self-understanding of their capacities and limitations. Reflection is central to how we, as human, makes sense of our world, and is an important part of how we learn. Reflective practice makes possible the cultivation of the discernment needed to make these appraisals. Discernment allows leaders to act—to make difficult choices that are in harmony with their deepest commitments, their concern for others, and the need to do the right thing in the situation at hand. They stand by their core moral values underpinned by the belief that each person is created in the image of God and that each of us is intended to serve a purpose greater than him or 7 herself. Leaders act on these values even when it may be more convenient and profitable to turn away from their convictions. Each recognizes their uniqueness (knowledge, skills, and experiences) and courageously steps in to bring change rather than withholding their gifts or avoiding the risks. At the same time, discerning leaders embrace innovation when such flexibility may achieve a better solution addressing the challenges they face. Reflecting the characteristics of early Jesuit priests, such leaders “free themselves from inordinate attachments that could inhibit risk taking or innovation; they become poised to pounce imaginatively on new opportunities…. Loyola called this, ‘living with one foot raised’.”18 Thus, the capacity to act in courageous ways despite a variety of pressures reflects a life ordered in its priorities and beliefs. Leaders also do not avoid the struggle between the needs of their organization and the interests of the people in it. Instead, they face the difficult dilemmas and seek solutions consistent with these values. Continual reappraisal of one’s direction provides the compass that guides daily decisions; the discipline to engage in this process is self-leadership.19 The discerning leader integrates this knowledge and personal awareness, which allows for greater insight and informed, thoughtful choices.20 C. Objectives for Leader Development We aspire that all members of our Rockhurst community be encouraged and supported to fully grow and mature as individuals and leaders. In this section we describe objectives which will serve as a basis for the development of our leader development programs. Our desire is to call each of our students, faculty and staff to achieve the following objectives: Understand your uniqueness. Develop your capabilities, your values, and your worldview. Develop life-long skill in self-examination and self-development focused on core values and personal goals and your uniqueness. Motivate yourself and others to recognize and pursue worthy aims. Confidently innovate and adapt to lead with integrity in a changing world. Through service to others, learn to engage others with a positive, loving attitude.21 8 As stated earlier, leader development at Rockhurst includes developing the leadership capacity of all students, faculty, and staff. Though each group is in a different stage of life and the approach to development may differ, the objectives are pursued by all groups. Nevertheless, each of the objectives above reflects our desire for each member of our community. Programs to achieve these objectives are being considered and over the coming years will be developed in order to achieve these worthy purposes. At present, we envision achieving these objectives using a twofold framework. The first component of the framework is a university-wide portion that, over time, provides a foundation of self-awareness and exposure to key leadership concepts for all members of our community. This portion is also intentionally constructed to encourage or facilitate participation across our community including staff and faculty and students. For undergraduates, their exposure to, and interaction with, a variety of experiences provides the chance to deepen understanding of themselves as leaders. Over time, concepts are expanded and deepened through practical opportunities to develop their leadership skills. For example, an early exercise might include a short reflective essay entitled, “My Philosophy of Leadership.” A later essay might include instructions to reevaluate this earlier essay following the student’s attendance at a presentation on leadership by an invited speaker. Students might also be asked to reflect on the connections between their emerging philosophy and a class project where they were able to serve in a leadership capacity. The second portion of the framework involves specific programs developed by individual schools. These programs would extend and add to the university-wide foundation. Participation could be optional and perhaps based on competitive selection. Individual school programs would reflect understanding of the segments of society and the roles their students will have upon graduation. Both the universitywide and school-specific portions of the leader development program would be anchored in the Ignatian model of learning and leader development, which is summarized in the next section. D. Model for Learning and Leader Development The purpose of this section is to provide a model for how Rockhurst University can use a uniquely Jesuit understanding of learning to guide development of the programs to achieve the objectives just described. As mentioned above, leader development applies 9 to all members of the Rockhurst community, and the model described here, though described mostly from a traditional student’s perspective, can readily be adapted by others. It is incumbent for all participants in this process of leader development, whether student, staff, or faculty, to determine how best to incorporate this model into their roles at Rockhurst. Learning and development occurs whenever a person engages in an event, then uses a process of refection to gain new understanding, and then, allows that new understanding to influence one’s future behavior. This model of development suggests that after reflection, students engage in an intentional process of recording the observations and insights that emerge from their reflection. Deeper understanding can be achieved out of the struggle to find works to describe emerging impressions and understanding. Additionally, when we interact with others as part of our learning process, deeper understanding can often emerge. Effective learning includes a collaborate component as we develop our thinking and test our ideas. The model presented below is derived from the Society of Jesus’ statements on the nature of Ignatian pedagogy but is composed of six elements, one more than suggested in the Jesuit document, “Ignatian Pedagogy: A Practical Approach.” 22 The figure below summarizes the model: Experience Evaluation Action Reflection Recording Context FIGURE 1: ROCKHURST MODEL FOR LEADER DEVELOPMENT Experience is the first component of our model. A new experience or event presents a choice: we either pass through the experience, taking little notice of it, or we perceive 10 the event as significant and valuable. In this later case an event presents an opportunity to use the experience as the basis for developing deeper understanding. Second, reflection is a central component for learning and figures prominently and distinctly in Ignatian thought. Through reflection, “students are impelled to consider the human meaning and significance of what they study and to integrate that meaning as responsible learners as they grow into persons of competence, conscience and compassion.”23 The recording of one’s reflections is the third facet and can be thought of as an important part of an active process of reflection. The process of recording one’s reflections serves as a way to clarify one’s emerging insight, and over time provides a way to reveal the changes in one’s knowledge. The fourth component, action, applies learning in daily life by acting on a new understanding that emerges from the processes of reflection and recording. Applying and testing one’s new understanding and behaviors enhances the possibility of personal development, growth, and learning. As expressed in “Ignatian Pedagogy,” the ultimate aim of action in education and in leader development is “that full growth of the person which leads to action—action, especially, that is suffused with the spirit and presence of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Man-for-Others.”24 Having learned from the ongoing interaction of experience-reflection-recording-and action, we ask ourselves, “Given what I have learned, how should I act differently?” The decisions we make to behave differently reflect the interaction of these first four steps. The fifth step, evaluation, resonates with the question just asked. But in evaluation, the time horizon is broader. The occasional periods of evaluation occur to identify themes and trends that emerge only over time. Here reflection occurs on a different level and is intended to reveal insights that elude us when we focus on the here-andnow. Evaluation reveals the more gradual evolution of habits, attitudes and behaviors. For example, a journal might be evaluated monthly or yearly to identify broader themes that are discernable only over time. Finally, this process is depicted as occurring within a context; each person is uniquely situated in a world of places, people, things, personal experiences and social relations. The dashed line around the model suggests that the context in which each person lives overlaps with others and is open to continual change. Even as a group is exposed to a new experience, each member may see the event differently. Hence, we see why appreciating our unique context is important as well as realizing why our 11 process of understanding requires interaction and collaboration around the experience that is being encountered. How often does a person engage in or complete this cycle? At Rockhurst, there might be particular events connected to leader development that each student participates in. Some of these experiences might occur in accordance with the academic calendar, others might occur within a particular course, and still others might emerge entirely at the discretion of the student. Whenever a new experience occurs and triggers active participation in the process, the cycle has restarted. To illustrate, consider a situation where a student has the opportunity to listen to a friend discuss an interesting article about how a leader handled a difficult ethical dilemma. She then reads the article for herself, and finds points of interest. She might engage in a discussion of the article with another person and also take time for a period of reflection to assess why the leader did what he had done, and how, she might have responded differently. She could then further clarify her understanding by recording her reactions, perhaps in a learning journal. Emerging from that process, she might begin to develop new views that would shape her own future behavior. In this example, the student self-identified an “experience” of interest and was intentional in evaluating and learning from it. The process might have taken an hour or two or perhaps days. Each time the student thoughtfully enters and navigates this cycle, her development is fostered. Since this cycle recurs each time the student responds to an event, the reflective process is perhaps best visualized as a coil with seemingly endless cycles that occur over a much longer time that generates a much deeper understanding of self, others, and of life’s journey. The model suggested here provides a way of opening a discussion not only of what specific processes Rockhurst might use to achieve our mission more fully but also to ask what we might do across the campus to broaden and deepen our focus on leader development. The Rockhurst community typically offers three sources for student experiences. First, students themselves initiate some experiences when they recognize and reflect upon events of their own choosing. An example might be gaining selfawareness of their unique ability as a listener as they reflect on recent interactions with others. Second, the person then might consider how to strengthen that skill further. Individual academic programs provide this second kind of experience primarily as part of coursework where a host of situations or assignments act as the basis for reflection and recording. A third kind of experience is provided by university sponsored events within schools, through co-curricular programs in student life, 12 athletics, or campus ministry or events made widely available to the community. Learning has the potential to occur whenever a student, faculty, or staff member takes the time to reflect and summarize important observations from an experience. Conclusion Rockhurst seeks to impact the world by “transforming lives and forming leaders” that view themselves as men and women for others. Ignatian tradition provides ample foundation for this aim with clear statements of values as well as providing a way to achieve these objectives through the model of learning we have described. This white paper has defined leadership and some of the values from which it emerges and we have provided a set of objectives to serve as the foundation for university-wide leader development programs. Finally, we have summarized the Ignatian approach to learning that can serve to assist in program development. We contend that leading in the ways described in this paper can contribute to meeting the great needs of the spheres of influence each of us interacts with as well as our global society. At Rockhurst University, our focus on leader development will serve to transform and prepare each member of our community to engage with competence and confidence, and have a positive influence in our families, communities, and organizations. WORKS CITED Allen, Scott J., Michelle Jones, and Anthony Middlebrooks. Head or Heart? And Other Challenges and Issues in Leadership Education. Association of Leadership Educators, Inc. Conference Proceedings 2007. http://www.leadershipeducators.org/Archives/2007/07proceedings.htm (accessed January 10, 2009). Arrupe, Pedro, and Kevin Burke. Pedro Arrupe: Essential Writings. Modern Spiritual Masters Series. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004. Avolio, Bruce J. Leadership Development in Balance: MADE/Born. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, 2005. “The Characteristics of Jesuit Education.” The Society of Jesus. http://www.sjweb.info/education/doclist.cfm (accessed January 10, 2009). Cooperrider, D. L. “Positive Image, Positive Action: The Affirmative Basis of Organizing.” In Appreciative Management and Leadership, Rev. Ed., edited by S. 13 Srivastva & D. L. Cooperrider, 91-125. Euclid, OH: Williams Custom Publishing, 1999. Day, D. V. “Leadership Development: A Review in Context.” Leadership Quarterly. 11, 4: 2000, 581-614. Gardner, Howard. Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. New York: Basic Books, 1993. George, Bill. Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003. Hall, D. T., & Seibert, K. W. “Strategic Management Development: Linking Organizational Strategy, Succession Planning, and Managerial Learning.” In Career Development: Theory and Practice, edited by D. H. Montross & C. J. Shinkman, 255-275. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1992. “Ignatian Pedagogy: A Practical Approach.” The Society of Jesus. http://www.sjweb.info/education/doclist.cfm (accessed January 10, 2009). Lewis, C. S. The Weight of Glory. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973. Lowney, Chris. Heroic Leadership: Best Practices from a 450-Year-Old Company that Changed the World. Chicago: Loyola Press, 2003. Kolvenbach, Father General R.P. Peter-Hans. “The Characteristics of the Jesuit Tradition.” Address at Georgetown University, December 8, 1986. McCauley, C, and Ellen Van Velsor, eds. The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leader Development. 2nd edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004. Norum, Karen. “Magis Leadership: Toward an Active Ontology of the Heart through Appreciative Inquiry and Servant Leadership.” International Journal of Servant Leadership, 2, 1: 2006, 455-482. Rockhurst University website and strategic planning documents. http://www.rockhurst.edu/about/glance/mission.asp Senge, P., C. O. Scharmer, J. Jaworski, & B. S. Flowers. Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future. Cambridge, MA: The Society for Organizational Learning, Inc, 2004. Wheatley, Margaret. J. Finding Our Way. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2005. 14 “Rockhurst University Strategic Plan 2007-2012,” Rockhurst University, http://intranet/Assessment/StrategicPlan2007-2012.asp 1 Strategic Direction # 4 from “Rockhurst University Strategic Plan 2007-2012,” Rockhurst University, http://intranet/Assessment/StrategicPlan2007-2012.asp 2 3 Pedro Arrupe and Kevin Burke, “Men and Women for Others,” in Pedro Arrupe: Essential Writings, (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004), 171-186. 4 Though the terms leader development and leadership development may seem synonymous and are sometimes used interchangeably, in the research literature they are not. Here, the focus is on leader development. McCauley and Velsor distinguish the two as follows: “Leader development is viewed as ‘the expansion of a person’s capacity to be effective in leadership roles and processes,’” while leadership development is defined as “the expansion of the organization’s capacity to enact the basic leadership tasks needed for collective work: setting direction, creating alignment, and maintaining commitment.” See Cynthia McCauly and Ellen Van Velsor, eds., The Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leader Development, 2nd edition, (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004), 2 and 18. Day synthesizes the notion of leader development saying, “The primary emphasis of the overarching development strategy is to build the intrapersonal competence needed to form an accurate model of oneself (Gardner, 1993, 9), to engage in healthy attitude and identity development (Hall & Sibert, 1992), and to use that self-model to perform effectively in any number of organizational roles.” The suggestion is that at Rockhurst, the primary focus is on leader development and that their leadership development continues within future contexts. See D. V. Day, “Leadership Development: A Review in Context.” Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 581-614. 5 Father General R.P. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, “The Characteristics of the Jesuit Tradition,” Address at Georgetown University, December 8, 1986. 6 Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, “Inspire,” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inspire. Online Entomology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=inspire&searchmode=none 7 8 KJV Dictionary as cited in Karen Norum, “Magis Leadership: Toward an Active Ontology of the Heart Through Appreciative Inquiry and Servant Leadership,” International Journal of Servant Leadership, 2,1 (2006): 455-482. 9 Norum, “Magis Leadership,” 457. She cites: Cooperrider, 1999; Quinn 2004, Senge et.al., 2004; and Wheatley, 2005. 10 Chris Lowney, Heroic Leadership: Best Practices from a 450-Year-Old Company that Changed the World (Chicago: Loyola Press, 2003), 208. 15 11 According to Lowney in Heroic Leadership, “Leadership springs from within and finds its expression through actions with others. Leadership is evident in both who one is and what one does, manifested in both a person’s actions and way of living,” 205. 12 Sources include: Bill George, Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Value (Jossey-Bass, 2003); and Chris Lowney, Heroic Leadership (Loyola Press, 2003). 13 This belief is consistent with Rockhurst University statement, “…every one of our students is a unique reflection of God and without the fullest development of that student’s gifts and potential the world will be diminished,” The Mission and Values of Rockhurst University: Learning, Leadership, and Service in the Jesuit Tradition, January, 2007. http://www.rockhurst.edu/about/glance/mission.asp 14 The idea that leader development is an ongoing process is incorporated in the model for leader development adopted at the Center for Creative Leadership. Their model indicates that development occurs within an organizational context when members combine a “variety of developmental exercises” with an “ability to learn.” As members assess their experiences, development occurs. See McCauly and van Velsor, Handbook of Leadership Development, 4. 15 McCauley and van Velsor capture the significance of the long view in both leader as well as leadership development when they note, “…if there is one key idea to our view of leadership development—an overarching them that runs throughout our work—it is that leadership development is an ongoing process.” See Handbook of Leadership Development, 22. Another reason for taking the long view is found in the inherent complexity of the endeavor. Allen, Jones, and Middlebrooks further illustrate the challenge. They quote from Jay Conger’s book, Learning to Lead: "Most would agree that to seriously train individuals in the arts of leadership takes enormous time and resources—perhaps more than societies or organizations possess, and certainly more than they are willing to expend." See Scott J. Allen, Michelle Jones, and Anthony Middlebrooks, Head or Heart? And Other Challenges and Issues in Leadership Education. From Conference Proceedings 2007, Association of Leadership Educators, Inc., http://www.leadershipeducators.org/Archives/2007/07proceedings.htm. 16 In The Weight of Glory, C. S. Lewis said, "There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilisations - these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit— immortal horrors or everlasting splendors. ... Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.” See C. S. Lewis. The Weight of Glory (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1973), 1415. 17 Lowney, 31. 18 The notion of “indifference” has a uniquely Jesuit meaning that, when embraced, allows the person to act out of one’s values and orientation on worthy purposes. Lowney, 160, 281-2. 19 Lowney, 98. 16 20 The Holy Bible, New International Version, Romans 12: 2, 3. “Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God's will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will.” 21 Adapted from Lowney, 294-295. 22 See “The Characteristics of Jesuit Education” and “Ignatian Pedagogy: A Practical Approach.” The document “Ignatian Pedagogy” goes on to say that “Pedagogy, the art and science of teaching, cannot simply be reduced to methodology. It must include a world view and a vision of the ideal human person to be educated. These provide the goal, the end toward which all aspects of an educational tradition are directed” (11). 23 “Ignatian Pedagogy,” 31. 24 “The Characteristics of Jesuit Education,” 167, and Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S. J., Address, Georgetown, 1989, cited in “Ignatian Pedagogy,” 12. 17