Document 16069403

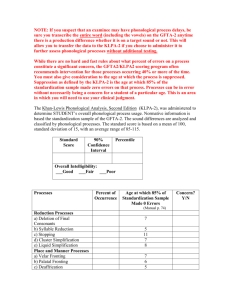

advertisement