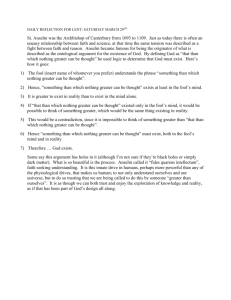

The Perfect God Anselm’s clever trick

advertisement

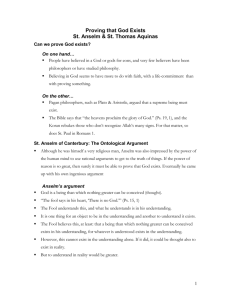

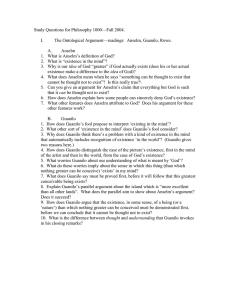

The Perfect God Anselm’s clever trick St. Anselm (1033-1109), Archbishop of Canterbury Faith Seeking Understanding • If anyone does not know, either because he has not heard or because he does not believe, that there is one nature, supreme among all existing things, who alone is self-sufficient in his eternal happiness, who through his omnipotent goodness grants and brings it about that all other things exist or have any sort of well-being, and a great many other things that we must believe about God or his creation, I think he could at least convince himself of most of these things by reason alone, if he is even moderately intelligent. (Monologion) Background: The argument of the Proslogion • The fool has said in his heart, there is no God. (Psalm 14:1) • How can a believer answer the fool? • Anselm claims that it is part of the nature of God to exist. • His argument is called ontological (reason about being) because its premises turn on what we understand God to be, and its conclusion is that such a being must exist. The Argument I 1. We believe that You are something than which nothing greater can be thought. 2. (I)t is one thing for an object to exist in the mind, and another thing to understand that an object actually exists. 3. Even the fool… is forced to agree that something-than-which-no-greater- canbe-thought exists in the mind. The Argument II • (S)urely that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-bethought cannot exist in the mind alone. • For, if it exists solely in the mind, it can be thought to exists in reality also, which is greater. • If, then, that-than-which-no-greater-can-bethought exists in the mind alone, this same thatthan-which-no-greater-can-be-thought is thatthan-which-a-greater-can-be thought. • But this is obviously impossible. The Argument III • (T)his being exists so truly that it cannot be even thought not to exist. • For something can be thought to exists that cannot be thought not to exist, and this is greater than that which can be thought not to exist. • Hence, if that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-bethought can be thought not to exist, then thatthan-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought is not the same as that-than-which-a-greater-cannotbe-thought, which is absurd. Aftermath • Why, then, did ‘the Fool say in his heart, there is no God’?... Why indeed, unless because he was stupid and a fool. • The challenge here: if the fool really thought there was no God, he did precisely what A has argued he cannot do. • So Anselm has to explain in what sense the Fool could believe there is no God, even though we cannot really think that this being doesn’t exist. • How does he do this? Responses • How do we go about criticizing arguments? • Standard: Attack one or more premises, or attack the link between the premises and conclusion (i.e. deny that the conclusion really follows). • But there are other kinds of response: Consider Guanilo’s “On behalf of the Fool”, which takes two different tacks. First question: how could Anselm’s argument possibly work? • Guanilo begins with the distinction between what is thought of in the mind, and its existing in the world: “…it cannot be doubted that this truth is one thing, and the understanding which grasps it is another.” • He also worries whether we really do have a proper idea of this being: “… neither do I know the reality itself, nor can I form an idea from some other things like it, since…it is such that nothing could be like it,” and “It is rather (as) one who…thinks of it in terms of an affection of his mind produced by hearing the spoken words” Consequences • It’s not clear to G that this thing is in the mind; what he accepts is only a verbal grasp of it: “I do not concedethat it exists in a different way from that…when the mind tries to imagine a completely unknown thing on the basis of spoken words alone.” • So G rejects a premise of Anselm’s The Island • The story: a wonderful island, better than all other islands… • It’s easy to understand these words. • But if the story-teller goes on to say, ‘and you must believe this island exists, since it is the most excellent island, and it wouldn’t be all that excellent if it didn’t exist’, we would not be convinced. • So G claims A needs first to prove the existence of this wonderful being, before trying to make a necessary link between the idea of the thing and its existence. Closing Shots • G. reassures us about his orthodoxy. • But at the same time, G. emphasizes that I can be certain of things (such as my own existence) while recognizing that they could be otherwise, and asks, if I can think of myself as not existing while being certain that I do exist, why couldn’t I also think of God as not existing despite my certainty that he exists?