2001 Corporations Outline I. Some Basics

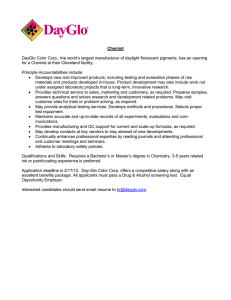

advertisement