.

Sexual Harassment

& Gender

What is Sexual Harassment? How is

Sexual Harassment viewed

Responsibilities, Organizational

Policy Statement, Different

Perspectives & Research Findings

(wk 6)

SexualH

1

U of Lethbridge

(Personal Security Policy)

Harassment:

• conducts or comments-intimidating, threatening,

demeaning or abusive. May be accompanied by

direct/indirect or implied threats to grade (s),

status, or job.

• Between people of differing authority or/similar

authority

• At individual/group

• Impact of creating an hostile environment:

hostile & limits individuals in the pursuit of

educational, research, work or personal

development goals

SexualH

2

Definition

• Includes but not limited to unwanted sexual

advances, unwanted requests for sexual favours, &

other unwanted verbal or physical conduct of a

sexual nature either explicitly/implicitly making a

term or condition of an individual’s educational,

employment or personal development progress..

• Includes hazing: inc but not limited to initiation

activities: abusive or humiliating & which subject

the object of the activity to physical or emotional

danger (http://www.uleth.ca/policy/ for further info)Subtle (contrary to acceptable standards),

Harassment (potential physical discomfort &

emotional anguish) & Dangerous Hazing (coercionuse of drug, alcohol)

SexualH

3

How to deal with SH by David J. Miramontes (84). San Diego: Network

Communications, Inc.

Test your own perceptions of what SH invloves:

•Repeated questions about your personal life

•Sly innuendos

•Questions about your “interests”

•Suggestive pictures around ypur work

•Compliments on your figure

•Comments on your “build”

•Unnecessary personal contact

•Frequent use of endearments – “honey”

•Sexual propositions

•Showing dirty cartoons

•Telling dirty “jokes”

•Excessive “dirty or swearing” talk

•A pass

•Sex oriented verbal “kidding” or abuse

•Suggestive body movements

SexualH

4

Do you find it a dilemma to label each one as SH?

Why/

1. Defining the problem by different people – differs?

2. Behaviours offensive to one person is not the

least bothersome to some others

3. Key issues: what bothers or pleases the

individuals involveda) 2 workers enjoys telling dirty jokes & no one

hears the jokes - not a SH case.

b) If a third worker overhears & is offended by the

jokes, this cld be a case of SH under the quality of

environmental issue.

SexualH

5

The strongest cases of discrimination due to SH wld

involve:

• Disrespect and prejudice which is :excessive and

shameful”

•Unwanted or unwelcome sexual advances, imposed

by a supervisor, manager or co-worker of an

employee

•A connection between the resistance to the sexual

conduct and the denial of job opportunities

•Conduct may or may not be sexual in nature, but in

some instances an individual may “perceive the

conduct as sexual

•A negative effect on the “environment”

SexualH

6

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(EEOC) – 1980 Fed Guidelines as part of 1964 Civil

.

Rights

SH as

“Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, &

other verbal or physical conduct of a SH nature” conduct

when:

• Submission to such conduct is made either explicitly or

implicitly a term or condition of an individual’s employment

(hire, fire) – (Employment Condition);

• Submission to or rejection of such conduct by an

individual used as a basis for employment decisions

affecting such individual (promotions, raises) –

(Employment Decisions);

• Such conduct has the purpose of effect of unreasonably

interfering with an individual’s work performance or

creating an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working

environment (unwanted behavior, ma be sexual in

nature)- (Offensive Working Environment)

SexualH

7

• Unwelcome conduct

- detrimental effect on work environment or job

performance

• Quid pro quo

– employment or job performance is conditional on

unwanted sexual relations

• Hostile work environment

– an intimidating, hostile, or offensive working

environment

SexualH

8

Who’s responsible? EEOC

•Management & Employees where the employer, its agents, or

supervisory employees, knew or should have known of the

conduct, unless the employer can rebut such apparent liability

by showing it took immediate & appropriate correction action.

•Non-employees where the employer, its agents, or

supervisors knew, or should have known of the conduct &

failed to take immediate & appropriate corrective action. EEOC

considers the extent of the employer’s control & any other

legal responsibility which the employer might have with respect

to the conduct of such non-employee.

Guidelines – the employers are strictly responsible for the acts

of SH regardless of whether the specific acts were authorised

or even forbidden & regardless of whether the employer knew

or should have known of their occurrence.

9

SexualH

EEOC procedures for employer to stop SH:

•Issue a strong & clearly stated policy against all

forms of SH in the workplace – well publicized posted

on all employee bulletin boards.

•A specific procedure to be adopted & publicized to all

employees

•Management, sups and employees should be

educated through an awareness program dealing

specifically with SH

•Complaints to be investigated promptly and seriously

•“Appropriate action” shd be taken if SH occurs

10

SexualH

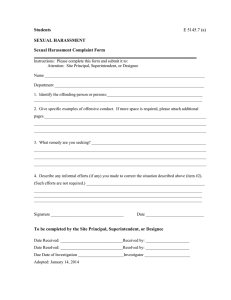

Date___________

SAMPLE CORPORATE POLICY ON SEXUAL HARASSMENT

It has always been the policy of __________that our employees should be able to enjoy a work environment

free from all forms of discrimination, including sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment is a form of misconduct which undermines the integrity of the employment relationship.

No employee – either male or female – should be subjected to unsolicited and unwelcome sexual overtures

or conduct, either verbal or physical.

Sexual harassment does not refer to occasional compliments of a socially acceptable nature. It refers to

behavior which is not welcome, which is personally offensive, which weakens morale, and which therefore

interferes with the individual ‘s effectiveness and work environment.

Such conduct, whether committed by supervisors, non-supervisory personnel or non-employees, is

specifically prohibited and disciplinary action will be taken f such conduct is found to be valid. Such behavior

includes: repeated offensive sexual flirtations; advances or propositions; continued or repeated verbal abuse

of a sexual in nature; graphic or degrading verbal comments about an individual or his or her appearance; the

display of sexually suggestive objects or picture; or any offensive or abusive contact.

In addition, no one should imply or threaten that an applicant or employee’s “cooperation” of a sexual nature

(or refusal thereof) will have any effect on the individual’s employment, assignment, compensation,

advancement, career development or any other condition of employment.

Any questions regarding either this policy or a specific situation should be addressed to the appropriate

supervisor or _______________________________at ________________________________________

___________________________________

_______________________________

EEO COORDINATOR

PRESIDENT

Source: How to deal with sexual harassment by David J. Miramontes. San Diego: Network Communications,

Inc (1984)

11

SexualH

What is Harassment? http://www.owjn.org/issues/sharass/guide.htm (Sang Hyeob & Team)

• Someone is harassing you if:

– he is doing things to make you feel uncomfortable;

– he is saying things to make you feel uncomfortable;

– he is putting you at risk in some way.

• The harasser will pick anything that makes you seem different

from him. You might be harassed because of your:

– gender;

– race;

– disability;

– age;

– looks;

– sexual preference;

– religious beliefs;

– family;

– birth place;

– political beliefs (including union activities).

SexualH

12

• Sexual harassment is any unwanted attention of a

sexual nature, like remarks about your looks or

personal life. Sometimes these comments sound like

compliments, but they make you feel uneasy. Sexual

harassment can include:

– degrading words or pictures (like graffiti, photos or

posters);

– physical contact of any kind;

– sexual demands.

• Racial harassment is any action that expresses or

promotes racial hatred and stereotypes. It can be

obvious or subtle. It can include:

– spoken or written putdowns;

– gestures;

– jokes;

– other unwanted comments or acts

SexualH

13

• Racial harassment can be hidden in questions or

remarks that seem positive. Here are some examples:

– "You are really pretty for a black girl."

– "Tell me what it's like to always have your head and hair

covered."

– "Women from the Philippines are better at that than Canadian

women."

– "Native people are so good at crafts."

• Different kinds of harassment can happen at the same

time. Here is an example.

• Leslie worked at a government office. She was called

"nigger" and "dyke" by her co-workers. A male co-worker

told her that he was the "real man" she always wanted

and offered to "change her. Anytime." She was told her

work was not as good as that of other, white, workers.

People said that she thought she was too good for her

job because of her university degree.1

SexualH

14

. Harassers often have authority in the

workplace. Your supervisor might be a

harasser. You might also be harassed by

a co-worker who wants you out of his way.

Or you might be harassed by someone

who works under you and doesn't like it.

The harasser wants to hold power over

you. He counts on your fear of

complaining. He may think you are an

easy target if there are few women where

you work.

SexualH

15

• `Sometimes harassment that occurs outside the

workplace affects your work. Actions like these can

cause problems or harm relationships among

employees:

– someone from work follows you or hangs around your home;

– phone calls and letters are sent to your home;

– things happen at staff parties or retreats.

• Some kinds of work can make you feel very vulnerable.

Here is an example:

• Regina works for a family as a live-in nanny. She came

to Canada for this job. She has no family and few friends

here. It will be several years before she can apply for

status as a landed immigrant or Canadian citizen. When

something goes wrong in her workplace, which is also

where she lives, Regina does not feel that she has

anyone to whom she can turn for help.

SexualH

16

`You have the right to ask your employer, your union, or an

outside agency like the Human Rights Commission to take

action against harassment.

• Shelley worked at a large corporation which she said

was "like a boys' club." She complained about sexual

harassment. The same day, she was harassed for

complaining. Only the supervisor, the man Shelley

complained about, and Shelley herself were supposed to

know. The "boys," even the ones in the union, stuck by

each other. They often made sexual remarks about

Shelley, or other women, to her face. They would joke

about not upsetting her. The workplace was often

postered with pin-ups. When Shelley handed a written

complaint to her supervisor, he said, "I don't need this

shit." After she left her job, she filed charges with the

Canadian Human Rights Commission against the

corporation. She charged her employer with

discrimination based on sex and with failing to provide a

work environment free of sexual harassment.

SexualH

17

`Is This Harassment?

• There are many clear-cut examples of harassment. Racist and

homophobic insults are harassment. When a boss demands

that an employee have sex or lose her job, it is clearly

harassment, and it is against the law. But there are many less

obvious examples. Many people are not sure if what they are

experiencing is harassment.

• Here are some examples of workplace behaviour:

– a man puts his arms around a woman at work;

– someone tells an offensive joke;

– someone says "You look great," or "Your hair looks terrific," or

"Did you get any last night?"

• These may or may not be examples of harassment. It depends

on the situation. Where two people are friends, a comment like

"your hair looks terrific" could be a compliment. If the same

comment is made by a stranger on the street, it feels very

different. If your boss leans over your desk and whispers the

comment in your ear while you are working, it feels different

again. The important questions are: do you feel comfortable

with this person making this comment? And does he have any

reason for believing that his comments are acceptable and

welcome

SexualH

18

Here is another example. A group of factory

workers have always told off-colour jokes. They

are all comfortable with each other. No one is

trying to offend anyone, and no one takes the

jokes seriously. Since they only work with each

other all day, they don't have to worry about

upsetting anyone else. The jokes might offend

some people, but they are not harassment in this

situation. If a new person joined their production

line and was bothered by the jokes, they should

stop telling them. If they persisted with this

behaviour in the presence of the new worker,

they would be harassing the new worker

SexualH

19

`When you don't have support from other workers, it can be

very hard to fight.

• Stephanie works in the finance department of a large public

institution. She is an Ojibway woman, and is the only aboriginal

employee in the department. Four months ago the department

was reorganized and she now works with a different group of

people. They all know each other and have worked together

before. They go out to lunch together, talk to each other, and

share jokes and slang. Stephanie is left out. She tries to deal

with the problem by talking to the only woman in the group,

Kate. Stephanie explains that she feels excluded and that she

thinks this harms the work. Kate denies anything is happening.

She says, "We're not racists, if that's what you mean."

Stephanie has said nothing about racism and is a bit surprised.

• After this, the workplace becomes unpleasant. It is clear to

Stephanie that the others are talking about her. One morning

she finds a piece of paper taped to her desk that says

"employment equity Indian." When Stephanie complains to her

manager, he offers to transfer her. He says, "This is a good

group. They work well together. You obviously don't fit in."

SexualH

20

• `What Does the Harasser Think He is Doing?

• Harassment can be confusing. You many wonder why

the harasser is acting this way.

– He might not think he is harassing you.

– He might be very surprised when you call what he is doing

harassment.

– He might not mean to harm you. He is treating you the way he

has learned to treat women.

– He might feel that he has the right to behave this way with

you.

– He might not think his actions have a big impact on you.

– He might want to push you out of a job that he thinks is for

men only.

– He might be angry because you are assertive or question his

way of doing things.

• BUT

– He might know he is upsetting you or harming you. He may

enjoy the challenge. Maybe he feels more powerful when he

treats you badly.

• And no matter what he thinks he is doing, harassment

is wrong. He can stop. SexualH

21

`What Does the Law Say Harassment is?

• There is more than one definition of harassment under the law. Some

forms of harassment are clearer than others. More work has been

done on sexual and racial harassment than on other forms. Some

other forms of harassment are still being argued in court.

Harassment challenges are happening in a range of workplaces. The

Ontario Human Rights Code and the Canadian Human Rights Act

name different forms of discrimination. You can turn to the section

on The Human Rights Commission for more information. Some

harassment cases have gone through the courts. The decisions that

the courts have made set some precedents, or guidelines, for new

cases.

• In these precedent-setting cases, the courts have decided:

– when employers are responsible for workers being

harassed;

– what is and is not acceptable behaviour;

– to recognize the seriousness of the effects of

harassment on women.

SexualH

22

`An Empirical Investigation of Sexual Harassment

Incidences in the Malaysian Workplace (Amie & Team)

• This paper presents the findings of a study which

investigates the factors that contributed to incidences of

sexual harassment at the Malaysian workplace. A

questionnaire survey which was partly based on the Sexual

Experience Questionnaire (SEQ) developed by Fitzgerald et

al (1988) was carried out involving 656 respondents. The

findings showed that sexual harassment incidences are

rampant at Malaysian workplaces. The findings also indicate

that it is aggravated by several factors related to both the

organization as well as the individual worker. Specifically, a

working environment characterized by lack of

professionalism and sexist attitudes biased against women

would cause female employees to be more prone to being

sexually harassed. When the various demographic

characteristics were studied, the findings reveal that the

sample of women employees who face a greater risk of

sexual harassment tend to fall under the category of the

unmarried, less educated, and Malay.

SexualH

23

• Sexual harassment at the workplace is happening all too

often with many factors being aggravated by both the

individual employee as well as the organization. Like the

United States, 35 percent to 53 percent of women are

sexually harassed in the workplace, whether it be one of

the two categories the Code of Practice on the Prevention

and Eradication of Sexual Harassment cites as

harassment: sexual coercion or sexual annoyance.

Sexual coercion is when the harassment directly affects

the employee’s benefits; while sexual annoyance is any

conduct that the victim feels is offensive. The Code is

completely voluntary at this point, but it is starting to make

progress in that the employer can end up having

mandatory disciplinary actions against those who choose

to break the sexual harassment rule.

SexualH

24

• `one of the reasons - the socio-cultural view

(Sociocultural Model) of women, that men have a

large dominance over women in this particular

culture.

• The study also pointed to a more likely for an

unmarried, younger woman to be harassed than

an older married woman. Also the women in

more of a subordinate, unprofessional position

are more likely to experience sexual harassment

than a more professional woman. The studies

Ismail and Chee conducted showed that 17.7% of

women in unprofessional work environments are

victims of offensive language directed towards

them then those in a professional work

environment (where there is an incidence rate of

7.7%).

SexualH

25

• `A question of dress also arose when conducting the

survey. There is a definite correlation between how sexily

a woman is dressed for work and how the amount of

sexual harassment she receives. 16.5% of women who

admit to sometimes dressing sexy for work have a high

rate of sexual harassment, while the women who are not

comfortable dressing in this manner experience a very low

rate of harassment.

• The demographics of the respondents also seemed to

have an affect on how often they fall victim to sexual

harassment. Women who have a higher education are

much less likely to be harassed and if they are, they do not

put up with it as long as those women with a low level of

education. And lastly, it was found that women who are

Malay experience much higher levels of harassment than

those who are non-Malay.

SexualH

26

`Sexual Harassment & Coping Strategies Amongst

Women in Manufacturing Organizations in Penang

Barathi Krishnan & Intan Osman (2003)

Sexual harassment is one of the most common forms of sexual

violation faced by women. Women are sexually harassed in the

streets, in public transport and at the workplace. Sexually

harassed women often find it difficult to seek appropriate

strategies against the harassers due to their social and

psychological backgrounds and beliefs. This study examined

whether women’s feminist attitudes, their gender-role beliefs and

demographic factors have any influence on the types of coping

strategies they would adopt in cases of sexual harassment. It

focused on emotion-focused and problem-solving strategies. Data

were collected via questionnaires from 207 female employees of

manufacturing organizations in Penang. The findings showed

that feminist ideology and gender-role beliefs have significant

impact on emotion-focused coping strategy. Race, education

level and position in the company showed significant impact

SexualH

27

towards problem-solving coping

strategy

Regardless of all its publicity and the fact that sexual harassment

problems have been acknowledged in the last two decades (L. G.

Seah, 2004), sexual harassment still remains hidden by most of its

victims in our society (Hotelling, 1991).

• Due to embarrassment, helplessness and fear of being known, and

worse still, of losing their jobs, most of the victims of sexual

harassment had to suffer in silence (Lim Ah Lek, 1999).

• In Malaysia (in the 1950s), a group of women estate workers in

Klang and Sitiawan, Central part of Malaysia went on strike in

protest of being sexually harassed (Wani Muthiah, 2001). a case

involving a female employee of Jennico Associates who has been

harassed by her employer was brought to the Malaysian court in

1999 (Wan Hazmir Bakar, 1999).

• Another case in point involved a woman employee of the National

Union of Bank Employees (NUBE) who was harassed and sexually

assaulted by Public Bank security guards in Kuala Lumpur (The

Star, December 4, 2002). These cases proved that incidences of

sexual harassment occur in varied working environment regardless

of the victim’s position in an organization

•

`

SexualH

28

•

`Gosselin (1984) concludes that sexual harassment is a

widespread phenomenon with social, economic and

psychological consequences for the victim. For the victims, it

often produces feelings of revulsion, disgust, anger, and

helplessness. It damages the victim’s health. It results in

emotional and physical stress and stress-related illnesses.

• Sexual harassment adversely affects employee morale, job

performance, productivity, and absenteeism among affected

employees. Women have been reported being fired or refused

advancement as a result of rejecting sexual advances (Errington

& Davidson, 1980). Moreover many female employees who face

sexual harassment choose to resign from their jobs rather than

fight or endure the offensive conditions (Gosselin, 1984).

• Although a small proportion of men experience sexual

harassment, it is mainly women in junior positions who are the

victims of harassment from male colleagues or superiors. Those

usually responsible for harassment have been proven in

previous research to be men of status either equal to or higher

than the victim and that physical harassment is more likely from

superiors than from colleagues (Stanford & Gardiner, 1993 in

Worsfold & McCann, 2000

SexualH

29

• `this study will examine whether women’s

feminist ideology, gender-role beliefs and

demographic factors influence women to

use different types of coping strategies as

these variables have been shown to affect

the way women cope with sexual

harassment (Brooks & Perot, 1991; Jensen

& Gutek, 1982; Fitzgerald et all, 1988;

Gruber & Bjorn, 1986; Gutek, 1985; and

Schneider, 1982).

SexualH

30

• The definition of sexual harassment is fairly broad (Northcraft

and Neale, 1994).

• The guideline developed by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC, 1980) which describes sexual harassment

as I) quid pro quo harassment, in which sexual conduct is made

a condition of employment; and 2) hostile work environment

harassment, in which sexual conduct unreasonably interferes

with work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile, or

offensive work environment.

• The Malaysian Trade Union Congress stated that sexual

harassment comprised unwanted sexual advances, including

unnecessary physical contact, touching or patting, suggestive

and unwelcome remarks, jokes, comments about appearance

and verbal abuse. It also includes leering and compromising

invitations, use of pornographic pictures at the workplace,

demands for sexual favors and physical assault (New Straits

Times, April 4, 1996).

• IRS (1996a) presented almost a similar viewpoint on what

employers considered to be sexual harassment based on a

survey on students studying hospitality management in the UK

higher education system from which majority identified sexual

assaults, demand for sexual favors, and unwanted physical

contact as definite examples of sexual harassment. Offensive

flirtation, gender related derogatory remarks, suggestive

remarks, and sexist and patronising behaviour also forms of

SexualH

sexual harassment by more than

half of the sample (Worsfold 31

and MacCann, 2000)

• Coping strategies refer to the specific efforts, both behavioral

and psychological, that people employ to master, tolerate,

reduce, or minimize stressful events. (Taylor, 1998).

• The two general coping are emotion-focused and problemsolving coping. The former is a method of dealing with the

emotional effects of sexual harassment problem without

changing the causal situation, where the victims will keep quiet,

ignores the problem, blame themselves or resign without taking

any action,

• Problem-solving coping strategy is an attempt to analyze the

problem and determine its best solution. This strategy includes

complaints to the police, and through company’s procedures or

discuss with company’s upper management. (Folkman &

Lazarus, 1985). Folkman and Lazarus’ (1985), found that victims

choose either emotion-focused or problem-solving coping

strategies as a method of dealing with sexual harassment.

• Most women use emotion-focused coping mechanisms which

are distancing and escape based, instead of problem-solving

coping mechanisms when trying to handle the problem of sexual

harassment (Folkman et al, 1985)

SexualH

32

• The study used the sociocultural model which focuses on

the larger social and political context in which sexual

harassment occurs.

• This model proposes that harassing behaviors at work are

an extension of male dominance in the society in which

the organization is embedded (Farley, 1978; MacKinnon,

1979). It posits that workers bring their gender roles and

stereotypes into the workplace.

• The model asserts that men and women are socialized

for stereotyped interactions to occur. Men are expected to

display dominating and aggressive behaviors, whereas

women remain more passive and blame themselves for

being victimized. As a result of this manner of

socialization, men view their behaviors as natural and

justified (Vaux, 1993).

SexualH

33

• The study also employs the sex-role spillover model (Gutek &

Morasch, 1982) which assumes that workers bring gender-based

expectations for behavior into the workplace, though these

beliefs are not appropriate for work which proposes that gender

identity is more salient than the worker identity.

•

Men and women, therefore, fall back on these gender-based

expectations in their work environments, where they are

inappropriate. Conflicts are more likely to arise in situations in

which the sex-role stereotypes are discrepant with the work

roles of the particular genders. These are places in which gender

is made more pronounced and is recognized over the work role.

•

Women are, therefore, more likely to experience sexual

harassment in nontraditional work situations involving works

other than nurturing or being a sex object.

•

Based on these two theories, the variables of interests: feminist

ideology and gender role beliefs towards sexual harassment will

be the determinants on the types of coping strategies women

would adopt if they are sexually harassed

SexualH

34

•

•

•

•

It has been reported that younger individuals are more likely to make a

formal complaint when sexually harassed than are older ones (Terpstra

& Cook, 1985) which is complimentary to the finding of Barak, Fisher,

and Houston (1992) that older, more experienced women are more likely

to perceive an environment as sexually hostile and therefore conclude

that their claim will not be taken seriously or that they would experience

some other negative outcome.

In a study of whistle-blowers' perceptions of organizational retaliation,

Parmerlee, Near and Jensen (1982) also found that younger individuals

were more likely than older ones to report instances of wrongdoing.

Given the evidence from these studies, younger individuals appear to

have more positive expectations concerning the outcome of reporting

incidents of sexual harassment than do older individuals. Brooks and

Perot (1991) found age and marital status have direct influence on

perceived offensiveness of the incident and that perceived

offensiveness have a direct influence on reporting the incident.

However, Gruber and Bjorn (1986); Ragins and Scandura (1995) found

that age, marital status, education do not consistently predict

differences in women's assertiveness in handling sexual harassment.

The inconsistent results could be explained by the fact that older

women tend to have more organizational resources such as seniority or

status which is likely to increase their assertiveness; but younger

women are often targeted for more severe and frequent sexual

harassment which in turn prompts them to be more assertive (Gruber &

Bjorn, 1986).

SexualH

35

• Sharifah (2001) in her study found position and

education level were important factors in adopting

positive coping strategies amongst women who

were sexually harassed. The most popular

strategies used were sharing the information with

trusted person and discussing with top

management. Sharifah (2001) claimed that most of

her respondents were from management level,

therefore they could have higher understanding on

exercising their rights as employees and at the

same time closer to the top management as

compared to the lower level employees. The same

results were also found in Wan Azhari’s (1996)

research which unrevealed that lower level

employee would prefer to keep quiet rather than

complain since they have fear of retaliation from the

harasser.

SexualH

36

• Feminist Ideology

• Gender-Role Beliefs

• Demographic Factors

COPING STRATEGIES:

• Emotion-focused coping strategies

• Problem-focused coping strategies

SexualH

37

• H1:

Women who holds conservative

gender-role attitudes would adopt emotionfocused coping strategies when encounter

with sexual harassment.

• H2:

Women with feminist ideology,

would adopt problem-focused coping

strategies against sexual harassment.

• H3:

There is a relationship between

demographic factors namely age, race,

marital status, education level, position and

duration in the company with the coping

strategies against sexual harassment.

SexualH

38

• Section 1 focused on the demographic data of the

respondents. The six variables are age, race, marital

status, education level, position in the company and

duration of service in the company.

• Section 2 was made up of three statements: 1)

Women are considered as sex objects at working

place;

2)Women behave in a seductive manner at work will

be rewarded more for that behavior than for

competence

at work; and 3) Sexual harassment at work reflects a

power relationship, male over female to

measure respondent’s feminist ideology (Brooks &

Perot, 1991).

• Section 3 has four statements

measuring respondent’s gender-role beliefs

(Hotelling, 1991; Brooks & Perot, 1991; & Gutek,

1985).

SexualH

39

• These are 1) Wage-earning women should limit their

employment to specific female jobs such as teachers,

nurses and secretaries; 2) In a work group, it is

woman’s responsibility to make coffee or take notes

at the meeting; 3) It is a woman’s responsibility to

prevent sexual harassment, 4) Women need to be

blamed and it is their fault if sexual harassment

occurs. Both independent variables were measured

based on 5 point Likert Scale: 1 being Strongly

Disagree to 5 being Strongly Agree.

• Section 4 contains six items to measure the types of

coping strategies that would be adopted

• (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985 and Hippensteele, 1996)

were measured based on 5 point Likert Scale:

• 1 being Strongly Disagree to 5 being Strongly Agree.

Items 1, 2, and 6 measure the emotion-focused coping

• strategy, while the remaining items measure the

problem-solving coping strategy.

SexualH

40

Coping Strategy

• I’ll keep quiet and blame myself

• I’ll be patient and ignore the problem

• I’ll make a complaint through Grievance

Procedure

• I’ll make a police complaint

• I’ll bring this matter to the court

• I’ll resign without taking any action

SexualH

41

200 responses were returned and usable, a response rate 50 %.

The majority of them (57.5%) are within the age of 21 to 30 years

old). In terms of racial distribution,

Malays were the majority (47.5%), followed by Chinese (30%),

Indians (20%) and other races (2.5%).

In terms of highest level of education, 5.0 percent respondents are

SRP / PMR / LCE holders. The majority of respondents (30.5%)

are SPM / MCE holders. Among the respondents, only 14

respondents’ highest levels of education are STPM (7.0%).

Diploma holders constitute 18.0 percent. Bachelor degree and

Master degree holders constitute 29.5 percent and 10.0 percent

respectively.

In term of position in company, most of the respondents were from

supervisory category. They constitute 45.5 percent from 200

respondents. This is followed by non-supervisory category with

30.0 percent. 15 percent were production workers and 9.5

percent were from managerial category.

In terms of duration of service in the present organization, 20.5

percent of the respondents had less than 1 year of service, while

18.0 percent had 1 to 2 years of service in the present company.

33 respondents representing 16.5 percent had 2 to 3 years of

service; this is followed by 9.5 percent of respondents with 3 to 4

years of service. 10.5 percent of the respondents had 4 to 5

years of service, while majority

of 25.0 percent had more than 5 42

SexualH

years of service in present company.

Results

. feminist ideology and gender-role beliefs have

significant impact on emotion-focused coping

strategy.

. feminist ideology and gender-role beliefs have

no significant impact on problem-solving

coping strategy.

• age, marital status and duration of service are

almost significant in influencing emotionfocused strategy that women would adopt if

they are sexually harassed

• age, race and position in the company are

almost significant in influencing problemsolving coping strategy adopted by women if

they are sexually harassed

SexualH

43

Discussion and Conclusions

• Feminist attitude was found to be a significant

predictor of emotion-focused coping strategy. This

study found that female employees who hold profeminist ideology will choose emotion-focused coping

strategy if they encounter with sexual harassment.

However, this finding found to be inconsistent with

past researches that have been done internationally.

International researchers such as Brooks and Perot

(1991); Schneider (1982); and Jensen and Gutek

(1982) found that women who have high feminist

attitude would adopt problem-solving coping

strategies if they encounter with sexual harassment.

One of the possible reasons for this inconsistency

could be the cultural difference among women in our

country and women in the country the research done.

Due to the differences in the environment and cultural

beliefs, women in Malaysia prefer to be silent and

ignore the sexual harassment problem although they

have a high feminist element in them.

SexualH

44

• Gender-role beliefs is found to have significant impact on

emotion-focused coping strategy. In other words, female

employees in this study who hold high gender-role belief

will use emotion-focused coping strategy if they are

sexually harassed. This finding is supported by

researches conducted by Brooks and Perot (1991);

Fitzgerald (1988) and Gutek (1985).

• They found that women who endorse gender-role beliefs

generally respond less assertively to sexual harassment

or choose emotion-focused coping strategy. In can be

said that women in our society still hold the traditional

cultural role for women as wife and mother and they

believe that wage-earning women should limit their

employment opportunities to specific female jobs.

• Women with this kind of gender-based expectations in

their work environment will blame themselves if sexual

harassment occur and choose to keep quiet and ignore

the problem.

SexualH

45

• Overall, the findings of this study show that women will

choose emotion-focused or the passive type of coping

strategies if they encounter sexual harassment.

• The results of this study seem to suggest that women in

this country are not playing an active role in preventing

and eradicating sexual harassment. Therefore, they need

to be encouraged to take problem-solving or the active

type of strategies if they are sexually harassed.

• One of the ways is by promoting the “Code of Practice

and Eradication of Sexual Harassment” in workplace. This

task can be taken by Human Resources Ministry and the

Women and Family Development Ministry.

• It is hoped that the findings of the study will help the

ministries to decide whether there is a need to have a

specific law on sexual harassment to educate, and

address issues/consequences arising out of

SexualH

46

• . Office

Romance and Power

• Co-workers believe that

employees in relationships abuse

their power to favour each other.

• Higher risk of sexual harassment

when relationship breaks off.

SexualH

47

• `

SexualH

48